It was 35 degrees inside my mom’s 4,000-square-foot log cabin in Ohio. She had the back-to-nature mansion built a few years ago, after her parents left her the land in their will. But she feared the contractors sabotaged it for an unexplained revenge, so she refused to turn on the heat.

“Back in a minute,” Mom said shortly after I arrived. I'd just flown in from New York to see her, but she was rushing off to her newly acquired alpaca barn. That was an hour ago.

Four excited poodles ran around a space heater, stacked boxes and collected junk. Very “Grey Gardens.” As I waited for Mom, I skimmed a 10-page handwritten letter on her desk, rainbow-colored Post-it notes stuck to the edges. She wrote about the end of the world, Armageddon, collecting an assortment of sale items, and how someday my twin sister and I would inherit the earth.

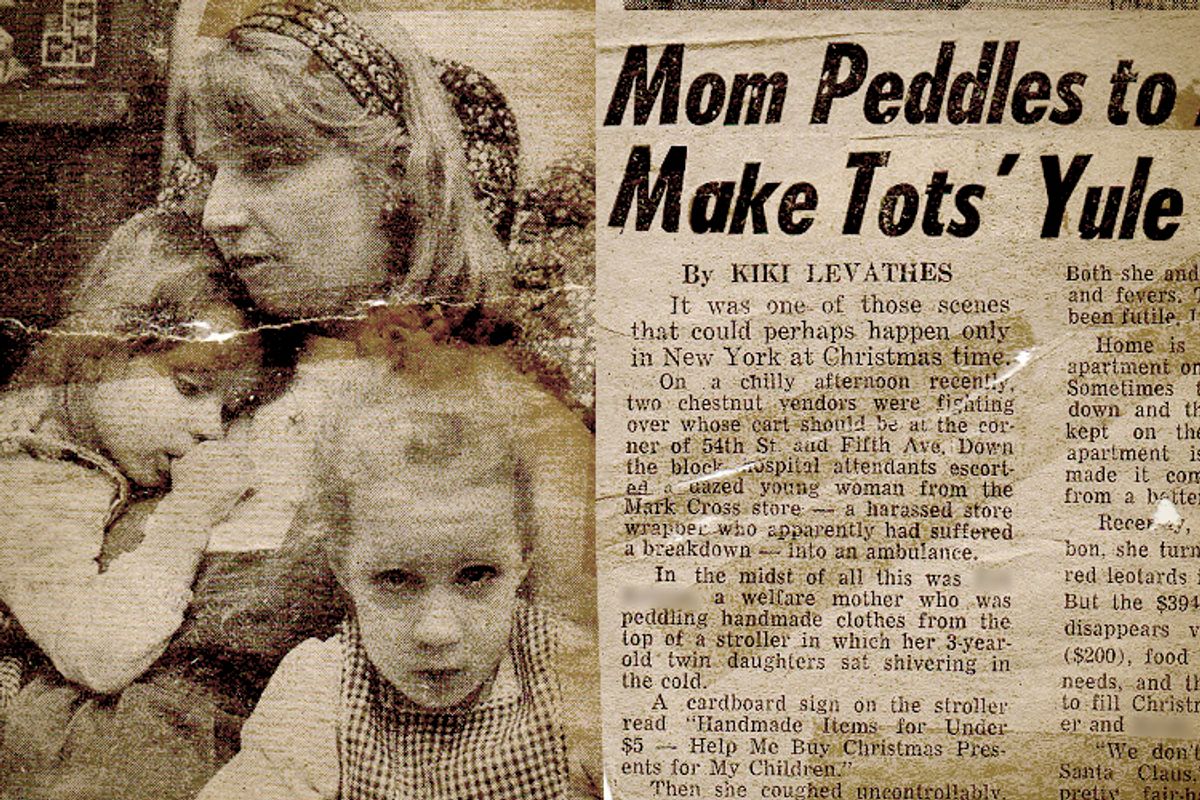

I looked up and saw an old, familiar newspaper clipping taped to a log. The headline read “Mom Peddles to Make Tots’ Yule.” The article describes how Mom, then 40, single and on welfare, sold homemade items on Fifth Avenue for under $5 while my twin and I sat shivering in the cold. We were 3 then. A cardboard sign, propped up on our stroller, reads, “Help me buy Christmas presents for my children.”

In the newspaper photo, I cuddle on Mom’s chest with my thumb in my mouth. Mom looks loving, and my twin peers up at the camera, her body out of frame. It struck me how innocent and close we were. By posting it, I assumed Mom was proud of that moment, and I was, too. I longed for us to be like that again. It was why I had come out here: to put our family back together before I started my own. But already, it seemed like everything was falling apart.

“It’s like ‘Little House on the Prairie,’” Mom said when she returned to the log cabin, her Birkenstocks covered in snow. She gave me a quick hug then climbed the spiral wire staircase, lugging a bucket attached to a rope and tossed it through a large hole in the ceiling, explaining that if I wanted privacy I could wash upstairs and use baby wipes because there was no running water in the bathroom.

My right shoulder tightened and lifted up, the way it did when she used to squeeze me too hard. I wanted a drink and to soak in a hot tub. It had been a year since I had visited Mom, and now I couldn’t wait to return to my friends and fiancé, Zack. I missed his lips, laugh and large family.

I opened the icebox and found hamburgers, baked potatoes and a salad from Wendy’s. Rag dolls, miniature Danish wooden horses and McGuffey Readers from our home-schooling days were placed near the toaster oven and compost toilet. The main room with a second floor balcony held: three Celtic dulcimers, an upright harp, a medieval lute, a Middle Eastern lyre, a Gibson guitar, a baby grand piano and a wooden recorder. The poodles' bells around their necks clinked as they ran over the makeshift couch that was a former church pew. One stopped and sniffed my tall black boots and the other peed in the corner.

“Why do you have all this stuff?” I asked, pulling my coat tighter.

“Without it, I’m just a leaf blowing in the wind!”

Mom’s white hair was thinning, tied in a ponytail down to her waist. Her pale light blue eyes glowed as she wrapped another shawl over her coat and came back down the stairs. “I’m either a pioneer or a bag lady, I dunno which.”

I wasn’t sure either. Back in New York, I told everyone that Mom was a free spirit turned Republican. I’d read Jeanette Walls’ memoir “Glass Castle,” about a woman struggling to accept her homeless parents, and I wondered: Could I ever do the same? Seeing the reality of my mother’s situation made the back of my neck tingle, and I wanted to peel the scabs off again. But I had made a promise to Zack to quit hurting myself, to heal once and for all.

My mom had long wrestled with a chaos of emotions and finances. But when my twin and I were 10 years old, something inside her cracked. She lost her job. She began picking at her skin. The bills piled up, along with notices from housing court, too, and within a year, we were evicted, on the streets, and homeless.

At a shelter, I told Mom I loved her, no matter what. Then we fell asleep next to crack addicts, the mentally ill and other families. Outside of a church, my family stood on line to collect a free foot-long block of orange government cheese. Volunteers said we were strong and courageous. My twin remained silent, stoic. I cocked my hip, took the handout, turned up the volume on the rap music that blared on my walkman, and strutted to the next soup kitchen with a limp like the pimps I had seen on the streets.

On the inside, though, I was filled with anxiety about being found out and feared I’d never break out of poverty. I began picking at my skin, too: I threaded my fingernail through my long brown hair and dug into the flesh on the back of my neck, causing it to bleed. Then I stuffed all my feelings in the hole. It was one thing I could control. And it felt good to peel off a scab, to know that it would heal miraculously and become new skin.

Two decades later, my twin tried to convince me that our family had gotten over our year-long “adventure” in shelters, subway cars and strangers' lofts. But I still struggled with self-harming, and our mother’s heart seemed homeless.

Mom giggled and then rushed toward me with a large manila envelope. The poodles barked in unison with anticipation.

“I have something for you! Share this with your sister. I don’t know why she can’t visit more often.”

“She’s pregnant and tired,” I said.

“Open it. Wait a minute.” She reached over and hugged me. Her grip was tight, her body soft and cushiony. It looked like her eyes were tearing up or maybe the cold air was making them drip.

The manila envelope felt empty, except for the bottom, which buckled out. I ripped into the envelope and out fell three diamond rings tied together with string. Mom explained they were from our ancestors. They were incredible. Large, no, huge, with white sparkles locked inside that turned to rainbows. I spun my ruby engagement ring off my finger and slipped on one of the diamonds. I felt dizzy and itched the back of my neck, but just a little and stopped.

“Mom …” I stalled, took a deep breath. “Can we sell these and maybe the land someday?”

“Don’t you dare!” The glow had left her eyes. It was dark outside. The moon peeked between the towering trees and coal plant lights blinked in the far distance. Mom suddenly looked hollow and sad. She continued, “I am kept here by God to protect and preserve.”

Mom described all the things she was buying on sale for us, to keep safe. She honestly believed that she was making up for what we lost when we were homeless. After years of drifting, she was desperately trying to put the pieces back together. But I didn’t want or need those things. I wanted a mom who would answer my questions about the past, be present, involved in my life, and excited about throwing a baby shower in the near future. I was tired of trying to take away her feelings of loss and paranoia and make her better.

Then Mom said something I’ll never forget, “I hope you love something in the future as much as I love you. Someday you will.”

A few days later I boarded the airplane for New York, which now felt like a different world. At night, I watched from my apartment window the city glowing back, my neighbors illuminating their dwellings with candles and neon signs. I thought of all the lives down below, billionaires and beggars and those in the middle, escaping wars at home or in foreign countries, doing their best to reinvent themselves between two rivers of splendor and squalor. I knew I had to forgive my mother for being unreliable and accept that she would never be a traditional mom. She was a woman, just like me, struggling, surrendering, and ultimately surviving. We had taken some wrong turns together, but the paths led both of us to unexpected places.

In my mind, I ran back into her arms like I did as a 3-year-old, and felt her heart racing through her blouse, touching mine. No matter how many years or miles separated us, I would always consider her warm embrace a shelter, even if just temporary. Tears streamed down my cheeks. I allowed all the anger, hurt and trauma to wash over me and grieved for those that I had lost.

Then I did what Mom was unable to do. I let go of everything: the disappointments, expectations, attachments to pain, and the idea of making it all better. Life and love were never going to be simple.

Within time, I stopped hurting myself, got married, returned to college, and studied journalism. Magazine and newspaper editors became my therapists via email, asking questions, forcing me to dig deeper or face having my personal essays rejected.

Today, as Mom predicted, I love something more than I ever loved anyone, my 3-year-old daughter named Daisy. She is the rainbow of happiness that was trying to wiggle out on those dark days.

This past summer, my husband and I returned to the log cabin in the woods. When the rains came, I watched Daisy rest her head on Mom’s chest. They held each other with kindness and care with no thoughts of the past struggles and difficulties. Mom hadn’t changed, but my feelings about her had. She enabled me to shape my own life, even when I couldn’t make sense of hers, by empowering me to believe that anything was possible and here was the proof.

Later in the day, Daisy and Mom bravely walked up the muddy hill toward the alpaca shed. They held hands and slipped a little. Then they marched on, never stopping, showing me the way, and leaving new footprints for generations to follow.

Shares