As snow fell across Washington DC on Tuesday, a group of Illinois home healthcare aides and their clients gathered outside One First Street NE. Inside, the Supreme Court was hearing argument in Harris v. Quinn, a case that could undermine not only the collective bargaining rights of the workers gathered outside, but also states’ abilities to manage their workforces. A majority decision by the Court’s conservative wing would overturn decades of precedent in labor and First Amendment law, and fundamentally alter the way millions of teachers, firefighters, police officers, and other public employees are managed by local and state governments.

While the issues are far reaching, the specifics of Harris v. Quinn turn on an Illinois state law passed in 2003, which allows Medicaid-funded home healthcare workers to choose a union and bargain collectively over wages, benefits and certain other working conditions. The workers selected the SEIU to represent them, and the union has delivered, negotiating a wage increase from $7/hour to $11.85/hour, with a planned raise to $13/hour at the end of this year; it also improved workers’ health benefits, and established new training opportunities for workers.

But the plaintiffs, represented by the National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation, argue that they (and all public employees) have a First Amendment right not to financially support their democratically selected union, even though that union is required to incur costs by negotiating on their behalf. (For a more detailed explanation of the issues involved, Lyle Denniston of SCOTUSblog has an excellent primer.)

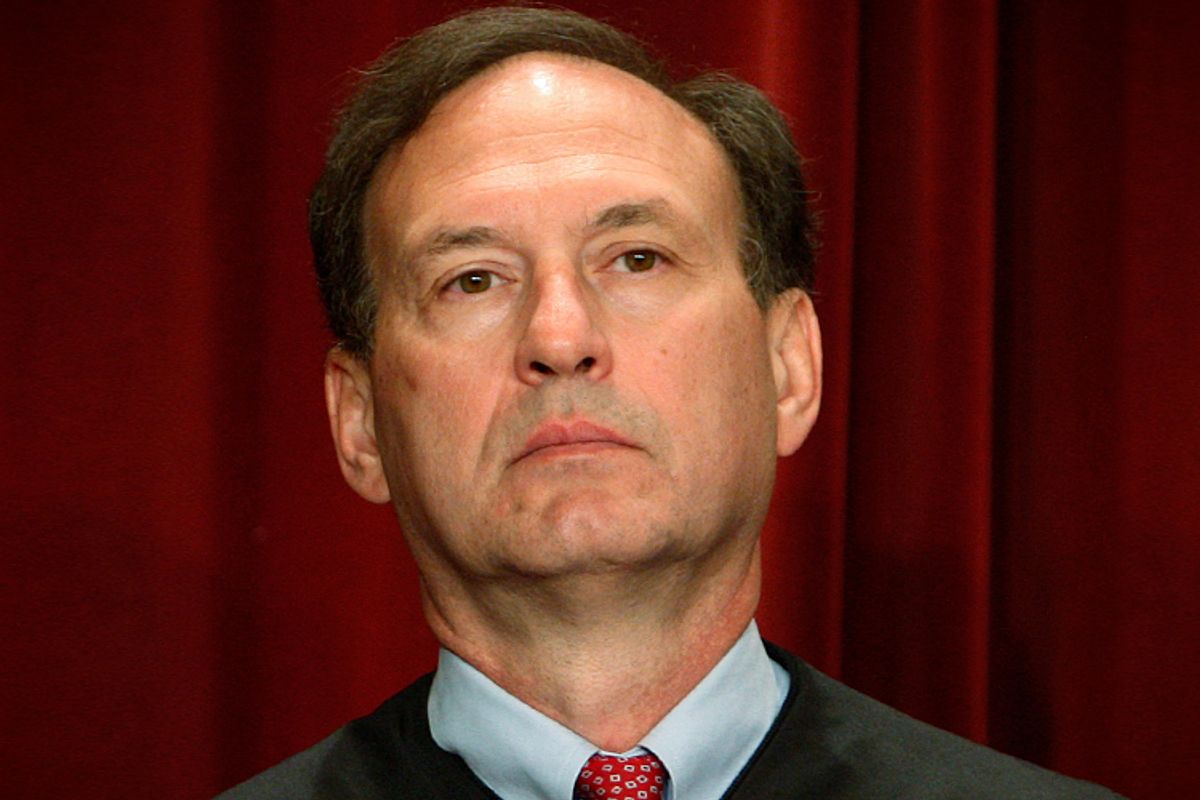

Judging by Tuesday’s oral argument, the outcome of the case is likely to be close: the Court seems split, with some members —particularly Justice Alito—advancing a cynical view of how unions operate. In a series of pointed questions to Solicitor General Donald Verrilli, Alito implied the Ilinois law in question wasn’t designed to improve working conditions and healthcare delivery, but was instead mere political payback. “I thought the situation was that Governor Blagojevich got a huge campaign contribution from the union and virtually as soon as he got into office he took out his pen and signed an executive order that had the effect of putting, what was it, $3.6 million into the union coffers?” (Actually the statute was enacted by a “large bipartisan majority,” a point made by the Solicitor General.)

Alito’s line of questioning reflects a widespread perception that employers agree to bargain collectively only if they are forced to. But that isn’t always the case; in fact, a majority of states have voluntarily committed themselves through their public sector labor laws to collective bargaining with at least some of their employees. (States also set the terms under which bargaining will occur; for example, some states limit bargaining to a handful of core working conditions.)

The home healthcare workers at issue in Harris v. Quinn illustrate exactly why many states see collective bargaining as a useful method of workforce management. Home healthcare aides (“personal assistants”) in Illinois are paid by the state an hourly wage to help clients with disabilities. For customers, having a personal assistant can mean living at home rather than being forced into an expensive institutional setting. From Illinois’s perspective, this means $600 million dollars saved each year. Yet personal assistants are generally poorly paid, and as a result the field is characterized by rapid turnover, even as demand for personal assistants is skyrocketing along with America’s aging population. This situation gives states a huge incentive to improve working conditions and wages, in order to keep up with the demand for home healthcare services.

Faced with these problems, the Illinois legislature found a bipartisan solution: collective bargaining, through a system in which an elected union is required to fairly represent all the personal assistants, who in turn pay their fair share of the costs of union representation (though no other union expenses). The resulting improvements that the SEIU negotiated for the personal assistants are typical of the gains unions often win for workers. But they also benefit Illinois: Improving working conditions and wages reduces costly employee turnover, helping the state meet a vital need for its most vulnerable citizens; improved training opportunities help personal assistants effectively serve their clients.

Given all this, it makes perfect sense for a state like Illinois to adopt a collective bargaining system. Yet, Justice Alito seemed skeptical on Tuesday. He asked why the union’s participation was “essential.” In other words, why Illinois wouldn’t simply provide these benefits sui generis, without a union in place?

It’s because Illinois, like many other states, concluded that collective bargaining is a better way to achieve its goals. When a state’s workers are stationed in thousands of different homes around the state, it’s difficult to communicate with them as a group in order to determine their collective interests, i.e., how the state can best work to retain a qualified workforce. But that’s where unions excel – their very existence hinges on effectively channeling worker preferences at the bargaining table.

Shares