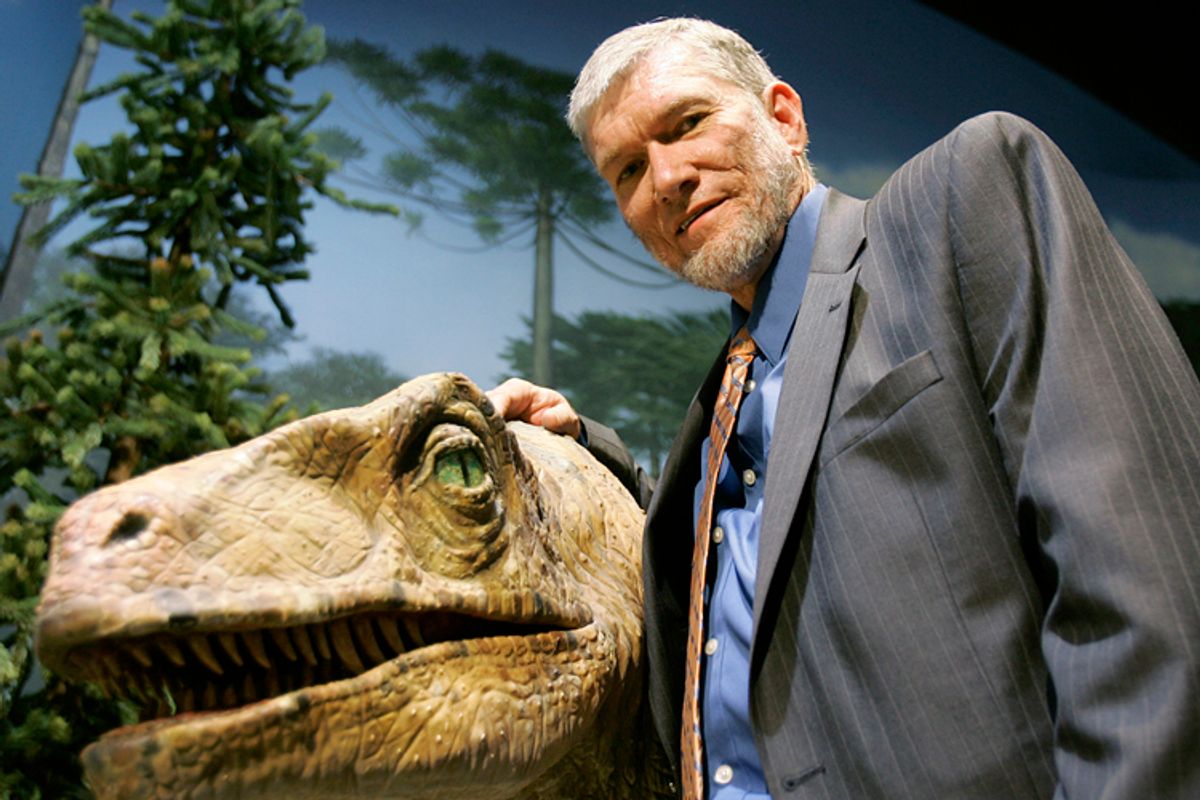

The Great Debate between science educator Bill Nye and creationist Ken Ham, live-streamed from Kentucky’s Creation Museum on Feb. 4, was a clash of accents.

Nye had the smooth tones expected of a fourth-generation Washington, D.C., resident, Cornell graduate and PBS regular. His opponent's accent was Australian.

Ken Ham had been a high school science teacher in his native Queensland, where he co-founded the Creation Science Foundation in 1979, before moving to the Institute for Creation Research in the United States in 1987.

Several schisms and realignments later, Ham heads the CSF’s U.S. and U.K. descendant, Answers in Genesis, promoting the idea that the Earth is some 6,000 years old, created directly by God over six 24-hour days, and subsequently devastated by a worldwide flood that killed all human and animal life except the elect breeding stock sequestered in a wooden boat built, at God’s command, by its captain, Noah.

A distinctly American combination of religious zeal and showmanship, producing media sensations from the 1925 Scopes Trial to this week’s debate, has created the impression of creationism as a U.S. phenomenon.

But creationism’s foremost historian, Ronald L. Numbers, wrote in his monumental study "The Creationists" that “no country outside the United States gave creationism a warmer welcome than Australia.” For the movement’s global reach, Numbers concluded, “American and Australian organizations” shared “much of the credit — or blame.”

Admittedly, surveys suggest anywhere from half to two-thirds of Americans believe some variant of the creationist view, compared with only 10 percent to one-quarter of Australians (depending on the survey). But Australian creationists are now showing the way.

The recent revelation that creationism-teaching schools in at least nine states were receiving over $11 million of taxpayers’ money per year might have startled Americans. But that is tiny compared to the taxpayer funds pushing creationism in Australia.

Since the 1970s, Australia has ratcheted up public funding to private schools, such that, in 2013, more than 34 percent of all school students attend them. More than 90 percent of these private schools are Christian. These include a large Catholic sector, and some old, establishment schools, which parents choose more for lavish facilities and old-school-tie networks than any religious content.

Nonetheless, the fastest growth is in more strictly religious schools such as the 91 affiliated with Australian Association of Christian Schools, whose members must assent to a Statement of Faith declaring “the supreme authority of the Bible,” meaning that “the Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments are God’s infallible and inerrant revelation to man” and “the supreme standard by which all things are to be judged.” The Statement also affirms that, “in pursuit of their task, Christian schools only employ Christian teachers and Christian non-teaching staff who are able to subscribe to this Statement.”

To proponents of “inerrant revelation,” the Genesis six days of creation are a touchstone.

In 2010 (the most recent figures available), AACS schools received over $357 million from state and federal governments.

Also in 2010, AACS was one of three umbrella associations of Christian schools (along with Adventist Education and Christian Schools Australia) that wrote to the South Australian Non-Government Schools Registration Board objecting to a new policy on science teaching.

The policy stated that the board did not “accept as satisfactory a science curriculum in a nongovernment school which is based on, espouses or reflects the literal interpretation of a religious text in its treatment of either creationism or intelligent design.” The associations successfully objected to the board’s attempt “to determine what cannot be taught within a non-government school or how materials will be taught,” and the statement was removed.

Together, the three organizations’ schools attracted in the region of $715 million in government support in 2010, or about 7 percent of the federal government’s total school allocation that year of $9.8 billion. (The bulk of public school expenditure is provided by state governments.)

Given the two countries’ historical parallels and constitutional similarities — Australia modeled its church-state separation phrases almost word for word on the U.S. First Amendment — Americans might well read the shape and extent of Australian public spending on creationist schools as a portent for their own future.

Public funding of religious private schools and increasing religious activity in public schools provide a warning about lack of vigilant protection of Australia’s once world-leading “free, compulsory and secular” public system.

Creationism with an Australian accent would not be the first time the U.S. followed Australia's lead. On Jan. 29, 2001, George W. Bush established the Office of Faith-based and Community Initiatives — opening a channel for government money into religious organizations. Similar initiatives were already well underway in Australia.

In 1998, a junior minister (now prime minister), Tony Abbott, abolished the Commonwealth Employment Service, a government agency to help job seekers find work. It was replaced by private providers, who tendered for contracts. The lion’s share went to church agencies. Other government services followed, such that, in 2013, economist Paul Oslington estimated that “approximately half of all social services in Australia are delivered by church-related organizations, often through contracting-out arrangements with government.”

As well as diverting taxpayer funds to private institutions, Australia is letting far more religion into the public school system than has been permissible, at least so far, in the U.S. Lacking an equivalent of McCollum v. Board of Education (the 1948 Supreme Court case that disallowed religion classes in U.S. schools), most Australian states mandate volunteers to enter schools for up to one hour per week to offer “Special Religious Instruction.” In Victoria, the evangelical group that delivers more than 90 percent of such instruction receives government funding, but the mandated alternatives (Catholic, Orthodox, Jewish, Buddhist, Hindu, Sikh, Bahá’i) do not.

In 2006, the Australian government instituted a National School Chaplaincy Program, under which both public and private schools could apply for up to $17,880 per year for a chaplain. Over 70 percent of the chaplains went to public schools, and over 90 percent of those were supplied through conservative evangelical Christian organizations.

Controversies associated with the program include a Queensland incident in 2011 when a public school chaplain arranged a lecture by Ken Ham’s CSF co-founder John Mackay, billed as a “science presentation examining the evidence for the Biblical account of Creation.”

Subsequently, schools gained the option to employ a secular “student welfare worker” instead of a chaplain, a move opposed by the conservative education spokesperson, Christopher Pyne, recently returned to government as education minister, who has stated his preference for chaplains alone.

In the U.S., charters, vouchers and tax credits divert taxpayer funds to creationist schools. Revised curriculum standards and so-called academic freedom acts sanction religiously inflected public school curriculum, while school prayer and sport chaplains mark border skirmishes in the religion-state tussle.

Australia’s whittled-back religion-state boundaries are a reminder of the many paths evangelizers find, especially in today’s deregulated education markets.

Watch for more imports with Ken Ham’s ascent.

Shares