If we look for unity in our politics today, where can we find it? Only in the claim that it has never been more divided. Everyone seems to agree on that. “The two parties have never been further apart,” wrote the liberal Ezra Klein last fall. “Republicans and Democrats are currently further apart ideologically than our political parties have traditionally been,” wrote the conservative Ross Douthat, a mere four days later. Only the fact of our polarization brings us together; we are fractured in everything except our mutual sense of brokenness.

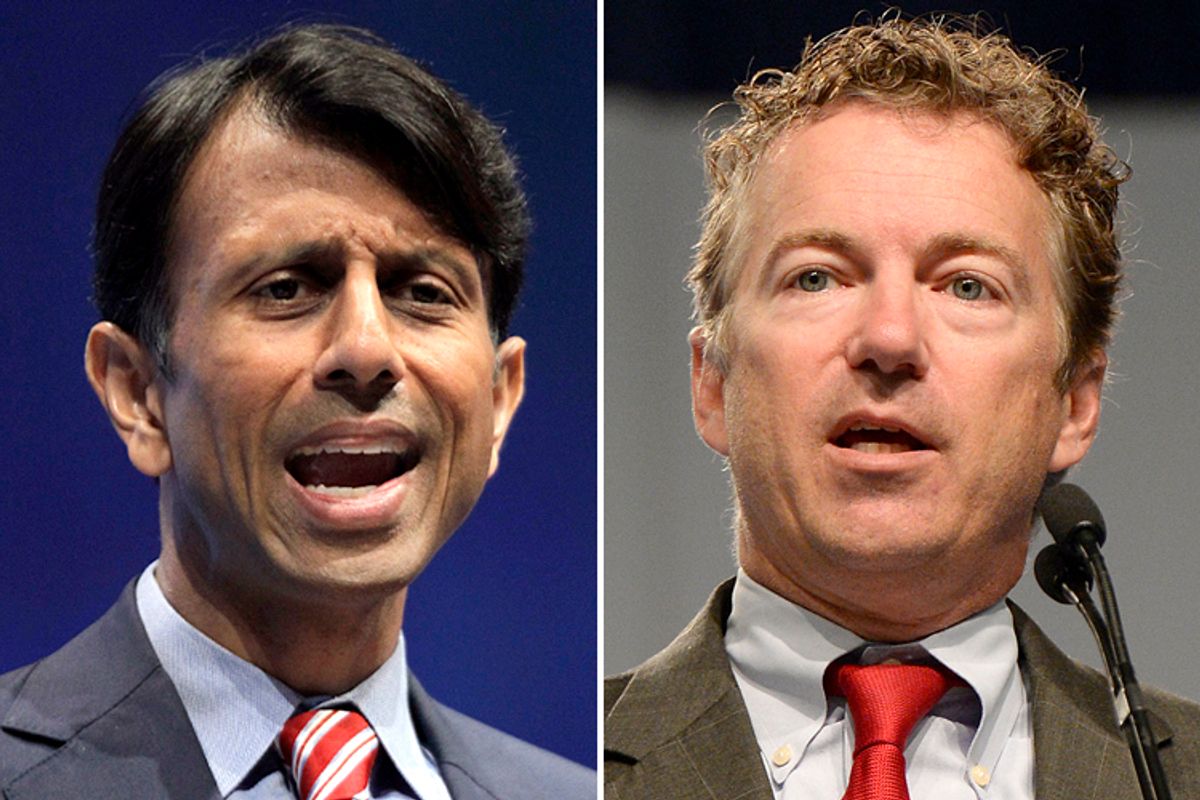

Many liberals attribute this situation to an increasingly radicalized Republican Party. Some Republicans do, too. Immediately after the 2012 election, Bobby Jindal, the Republican governor of Louisiana, lashed out at the “offensive, bizarre comments” of some GOP candidates, whom he accused of espousing a “dumbed-down conservatism.” Republicans, he insisted, must “stop being the stupid party.” The RNC’s own “autopsy” of the 2012 results, issued in March of last year, made many of the same points. (In kinder, gentler terms, of course.)

But some Republicans bridle at this kind of talk. Polarization suits them just fine. As they see it, there is only one alternative to being their kind of Republican, and that alternative -- namely, being a Democrat -- is truly a fate worse than death. Calls for them to be more “moderate,” more “reasonable,” strike them as calls to adopt policies like those of liberals -- advice they reject with great alacrity. David Limbaugh, brother of Rush, provided a characteristic formulation of this response not long after President Obama’s victory in 2008. Anticipating that Republicans would be pressured to work with Obama “on a wide variety of issues,” David Limbaugh cautioned that if “Republicans reduce themselves to offering merely liberal lite the next four years” they would do nothing but compound the damage of Democratic legislation.

But there is more to our predicament than disputes over policy. These differences, after all, aren’t so much the scourge of politics as the reason we have politics in the first place -- if everyone agreed about everything, we wouldn’t need elections. Our problem isn’t necessarily that Republicans support lower marginal rates for high-income taxpayers or smaller cost-of-living increases for Social Security recipients. We had a politics like that once -- as recently as the George H.W. Bush years -- and, though often fraught and volatile, it ushered in actual achievements. Things got done.

Our problem is that many of today’s most influential Republicans think of Social Security as a “Ponzi scheme” and identify the progressive income tax (originally introduced by Woodrow Wilson) as the focus of evil in the modern world. President Eisenhower famously counseled Republicans to accept the welfare state introduced by Progressives and New Dealers. Conservative energies, he insisted, would be better spent managing its pretensions -- and warding off Democratic excesses -- than in contesting its basic framework. And for the next 40 years or so, the Goldwater insurgency aside, this is more or less what they did.

But in the wave election of 1994, Bill Clinton’s attempt at health care reform -- “Hillarycare,” as Republicans christened it -- provided an issue focus for the Right’s cultural rage at the Clintons and swept in the Gingrich Congress. As the government shutdown of 1995 soon demonstrated, these were not Eisenhower -- or even Reagan -- Republicans. Something had changed. The ideological purification of the Republican Party, a process underway since the 1950s, was now producing politicians who were not content to be “tax collectors for the welfare state,” to borrow an epithet Gingrich hurled at Bob Dole. They had come not to restrain the modern state but to bury it. The scene of conflict between Democrats and Republicans shifted from the details of policy to the institutional framework within which policy is made. This conflict, in turn, is rooted in a profound clash of worldviews, a clash that reflects wildly divergent attitudes toward modernity.

To see this, let’s explore two different “creation stories” about political modernity. The first one, I think, is accepted by most Democrats and many Republicans:

The United States exists because of two moments in European history. Originally the country was shaped by its status as an outpost of European imperialism. As in most such cases, the colonizers struggled with indigenous peoples who were variously bribed, massacred, ignored, and exploited. (A later influx of African slaves added another layer to this sorry story.) The British colonies gained formal independence in 1783, but their basic institutions -- and intellectual elites -- remained deeply influenced by a second historical episode, the English Enlightenment. The first fact, the fact of distance and newness, meant that American society largely evaded the legacies of Europe’s feudal past; class distinctions in particular pressed much less heavily. The second fact meant that American politics reflected the Enlightenment’s emphasis on individual liberty (for white males, anyway) as essential for personal happiness and social progress. Allied with this was a belief that liberty is mainly threatened by powerful institutions with absolutist tendencies, be they governmental or ecclesiastical.

This was the template for American development until the last third of the 19th century. At that time new forces began to strain against its limits. Some of these concerned the marginalized groups mentioned earlier, women and African-Americans especially, who rightly agitated for more complete social identities -- identities that would include a broader panoply of rights and powers. Others derived from the enormous changes wrought by the Industrial Revolution. New technologies in communications, production and transportation swept away whole orders of life. American society had been mainly rural and agrarian; now it became increasingly urban and industrial. The locus of production moved from the subsistence farm to the factory. Suddenly it was possible to link locales previously separated by continental (or global) distances, so distribution escaped its largely regional confines and expanded accordingly. All of these changes spoke to an even more fundamental transformation: the reorganization of economic life around the modern corporation, an entity of unprecedented scope and scale.

These features of the corporation drove improvements in efficiency and productivity that would have been unthinkable mere decades before. This, in turn, brought about something truly singular in human history -- a genuinely middle-class society, in which most households engaged in commercial activity and experienced life as something more than scarcity or mere subsistence. But this progress came at a cost. The people who abandoned farms in the country for factories in the cities often encountered conditions that were harsh and inhumane. Hours were long and the work could be dangerous. Cities struggled to absorb the influx of urban laborers and to provide the infrastructure and social services they required. When it became clear that industrial capitalism was as vulnerable to booms and busts as earlier forms of market society, cities faced another challenge as well: that of managing unprecedentedly large numbers of people whom recession or depression could transform into an angry, immiserated proletariat.

As the 19th century gave way to the 20th, political actors evolved ways to accommodate these forces within the American system. The NAACP, founded in 1909, pressed the claims of African-Americans to the full citizenship promised by the Civil War amendments to the Constitution; in 1919, first-wave feminists finally secured women the right to vote. The Progressive movement, championed by both Republicans (Theodore Roosevelt) and Democrats (Woodrow Wilson), accepted corporate capitalism as the new economic order -- “The old individualism is dead,” Roosevelt once remarked -- but insisted that government act to limit its excesses and to regulate its behavior. Their early reforms sought to strengthen competition (antitrust laws) and to stabilize the financial system (the creation of the Federal Reserve), and also secured the abolition of child labor and a standardized work week. The spirit of these measures later enlivened the New Deal legislation of the 1930s and the Great Society programs of the 1960s.

And thus the modern American state emerged -- sometimes haphazardly, sometimes half-heartedly, almost always maddeningly slowly -- from the need to respond politically to the realities of the modern American economy and society.

The second story, on the other hand, is endorsed by the most activist elements of the Republican Party and the most influential members of the conservative commentariat:

America’s existence is providential. We are an exceptional people because our Constitution alone embodies the principles God established for His children, chief among them the paramount importance of individual liberty as the crucible of real faith and true virtue.

To be sure, America has stumbled along the way. Mistakes were made, slavery most obviously, but even a divine omelet requires a few broken eggs. The country largely hewed to its original inspiration until the later 1800s, when Lincoln claimed unprecedented powers for himself during the War Between the States. His was the original imperial presidency, and it awakened the federal government’s ravenous appetite for influence and control. One might chalk this up to the exigencies of the moment -- Lincoln did, after all, have a war to fight -- but in his wake events took a decidedly darker turn. Seduced by the siren strains of European secularism, America’s intellectual elites abandoned liberty in favor of equality. From their base in the country’s educational system -- including its most prestigious universities -- they gradually poisoned the minds of its political class. The result was socialism in economics and a radical egalitarianism in politics. The Progressives and New Dealers replaced the free market with an economy planned and controlled from Washington; feminists, civil rights agitators, and homosexuals turned the power of the federal government against traditional, time-honored values and mores. Now, in 2014, we have a government fatally unmoored from its original principles and an electorate largely duped and/or bribed into not noticing or caring. An embattled remnant of the population -- despised, ridiculed, harried -- preserves the pure American faith in its mainly rural redoubts in the South and West, but whether it can reclaim the country is increasingly in doubt. One thing, however, is certain: If it fails, America will be lost forever.

An obvious difference between these stories is how they judge the changes they describe. These changes -- in economics, the transition from an agrarian capitalism centered around individual producers to an industrial capitalism dominated by corporate power, with an associated scheme of social protections; in politics, the movement from white heterosexual male privilege to a more inclusive ethos -- chart the evolution of the modern world. They just are modernity. The first story accepts them as on the whole positive, but the second recoils from them in horror. In the economic innovations of modern life, the second story sees only an unholy engorgement of federal power and the loss of an aboriginal liberty; in its social transformations, only corruption and confusion. Its preferred vision, which is the vision of the Tea Party and its familiars in the right-wing media, is a vision of restoration: of the return of a world in which power remains in the hands of white heterosexual males who best their peers in solitary economic combat. Everyone else in this world is either an inferior to be pitied and watched over (women, poor whites) or an absolute other to be controlled and exploited (non-whites, homosexuals).

This wholesale rejection of modernity is certainly striking, but another aspect of the second story is equally problematic. The first, progressive narrative is at bottom a story of enlightenment, and in two senses. Most obviously, it embodies the Enlightenment’s emphasis on the emancipatory powers of human rationality. Modernity arises when we replace a blind acceptance of authority -- political, social, or religious -- with a reliance on the critical scrutiny of evidence and an experimental attitude toward human practices. But associated with this is a “lower case e” kind of enlightenment. Modernity, on this view, is simply what we get when we learn from our experience. Once upon a time we thought women were too emotional, too “flighty,” to trust with the vote -- but we were wrong. We thought non-whites were barely human and incapable of civilized life -- but we were wrong. We thought homosexuality was an unnatural perversion that poisoned the soul -- but we were wrong. And we thought that the market, left wholly to its own devices, was a self-regulating mechanism of perfect freedom. We were wrong about that, too.

The progressive narrative sees history as a value-laden process of empirical discovery. As our experience widens, as reason refines itself and our sympathies enlarge, we adjust our practices accordingly. But the second, reactionary narrative rejects enlightenment in both senses. It regards “The Enlightenment” as the moment when Reason exalted itself above Faith and mankind bowed down before the false idol of secular humanism. And it utterly rejects the idea that the modern state represents an adjustment to new realities. (If it admitted that the world has changed, this would force a question about the suitability of its pre-modern dogmas.) As the Right sees things, the “realities” of 2014 mirror those of 1776; only the way we think has changed. So it interprets the characteristic features of modern life as ideological emanations -- illusions foisted on a deceived public by the machinations of cloistered intellectuals. Modernity, for the Right, is what communism was for Joseph McCarthy -- a vast, intricate, fatal conspiracy.

Its virulent alienation from modern life is the foundational fact about the American Right. (It can be argued, of course, that this kind of animus is at the heart of right-wing movements generally.) Once we see this, we can understand both its paranoia and its sense of victimization -- as well as its stridency and shrillness. We can also understand its tortured relationship with the “reality-based community” -- with the idea that beliefs should be checked against facts, not facts against beliefs. The Right reverses the epistemic order of modern thought: it deduces reality from theory, not theory from reality. Its ontology is as faith-based as its social policy, and has to be.

Like many on the left, I often respond to especially egregious examples of right-wing perversity with a plaintive, “How can anyone be so dismissive of the facts?” But only those prepared to dismiss the facts -- especially that subset of facts we call “the modern world” -- could believe the things they claim to believe. The most basic lesson of modernity is that we must be prepared to change our minds. When we are not -- when insistence subverts instruction, and our beliefs are refreshed by resentment rather than experience -- we insulate ourselves from any possibility of empirical correction. Because the Right defines liberalism as a wholly false ideology, anything that lends it support, no matter how apparently well-grounded, must be in error. The a priori falsehood of liberalism guarantees the falsehood of any “fact” that seems to support liberal views. Counterexamples to Republican opinion therefore carry no weight and need not constrain their conclusions. The ultimate expression of this logic, engineered by media figures with ad time to sell and politicians with primary voters to placate, is the oft-remarked conservative “bubble” -- the self-contained universe of discourse in which true believers endlessly parrot the same views and interpret this as independent confirmation of their truth.

This shrillness and hermeticism, combined, produce the characteristic rhetoric of today’s Republicans -- a rhetoric that manages to be both portentous and self-parodic. They aren’t content to describe Barack Obama as a liberal Democrat with lots of bad ideas; he must be “the worst president ever,” a Manchurian Candidate by way of Kenya who wants to deliver the country to the Muslims, the Terrorists, the Black Panthers, or the United Nations. (Take your pick.) They can’t settle for arguing that “Obamacare” is flawed policy; they’re too busy warning us about “death panels.” Despite 80 years of economic practice (and theory) to the contrary, they must reject any counter-cyclical role for government and oppose an economic stimulus during the worst business downturn since the Great Depression. Cosmology and evolution are “lies from the pit of hell.” Climate science is a fraud. And the statistical models used to award Ohio to Barack Obama in the 2012 election are less solid than the blustery certainties of Karl Rove.

This situation is not without its comic aspects, as recent controversies about the racial identity of Santa and Jesus -- and the Biblically inspired thoughts of “Duck Dynasty” star Phil Robertson -- make all too clear. But the potential tragedy here cuts much deeper than the comedy. The reactionary narrative of modern life underwrites the casual slander of women who seek reproductive autonomy as “sluts,” just as it quickens efforts to still the electoral voices of non-whites and the poor. But the perversity of the Right’s vision is nowhere more evident than in its economic thought. The Paul clan’s crusade against the Federal Reserve is just one element in a much broader fantasy, one that longs to combine a 21st century economy with an 18th-century government. All would be well, we are told, if only we stripped off the encrustations of political modernity -- the regulatory agencies, the bureaucrats, the safeguards and oversight -- and returned the market to its pristine form. There stalwart yeomen will contend with each other in a Lockean state of nature, and a grateful land will reap the inevitable rewards.

It doesn’t occur to our libertarian fabulists that economic conflict in this world would not involve one yeoman farmer contending with another, but working- and middle-class Americans contending with -- Wal-Mart. Or Bank of America. Or Exxon. The modern state arose, in large part, in reaction to the modern corporation. This form of enterprise achieved truly great things, but also made possible a concentration of economic power never before seen in human history. Purely private entities suddenly became genuine rivals of governments and churches, and equally serious threats to the liberty of individual citizens. Like it or not, the simple fact is that the federal government is the only institution of sufficient scale to interpose itself between multinational corporations and American families. To remove it from the picture -- to “drown it in the bathtub” as Grover Norquist wants to do -- would leave average Americans utterly exposed to the tender mercies of a rapacious global capitalism. To the Rand Pauls of the world this sounds like the perfection of freedom. It sounded like something very different to Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson.

Under the influence of the Tea Party and its allies in the media, the Republican Party no longer seeks to govern with caution and realism. It seeks to bring back a lost world. This has created a politics in which policy disputes are simply proxy fights in a much deeper, more fundamental campaign: a war of worldviews. Is it any wonder that the present Congress is on track to be the least productive in the history of the nation? To collaborate constructively, parties must regard each other as legitimate actors within a political system whose structural principles they generally endorse (or at least accept). This condition is not satisfied when one party, under the influence of a revolutionary faction, recoils from basic features of that system. In such cases it will consider those who operate (and cooperate) within the system to be dupes (at best) or traitors (at worst). Constructive collaboration becomes impossible, and politics unravels into paranoia, paralysis and suspicion. Sound familiar?

The essential conflict in our politics today is not between Democrats and Republicans. It’s between Republican modernists, who have the numbers and a great deal (though not all) of the money, and an anti-modernist [faction] with energy and urgency and most of the microphones. In an article published last summer, I argued that the modernists would not displace this faction until it nominated one of its own for president and precipitated an electoral disaster of Goldwaterish proportions. I still think that analysis is likely to be correct, though last fall’s government shutdown, a humiliating defeat for the Ted Cruz-led Republicans, seems to have hastened the process a bit. Whatever the timeline, we should all watch the ongoing struggle closely. A great deal depends on the outcome.

Shares