Since at least the end of the Reagan administration, we’ve seen occasional pronouncements from political commentators about the impending breakup of the Republican Party, pulled in one direction by its fire-breathing conservative base and in another by corporate elites and Washington insiders. It keeps not happening. One factor here is just magical thinking on the part of liberals, along with the continual frustration of losing elections to an opponent who combines troglodyte social views with discredited economic fantasies and a paranoid, mythological foreign policy. (Let’s leave aside, for the moment, that on the latter two questions the Democrats are only marginally better.) Wouldn’t it be a nicer country if the nasty Republicans, and the millions of citizens who vote for them, simply went away?

Still, there really are significant divisions within the GOP, as the party’s panicked post-2012 retreat on immigration reform, and the humiliating aftermath of the government shutdown, have made clear. (With lightning speed, Ted Cruz went from Our Next President to Our Next Prime-Time Fox News Host.) To the immense frustration of the Republican establishment in Washington, the party faithful have repeatedly snatched defeat from the jaws of victory by nominating some Tea Party zealot or Christian flat-earther who blunders away a potentially winnable statewide election by saying something stupid about women and sex. As things stand, the Republicans have a good chance of retaking the Senate majority in this year’s midterm elections, even though they have no coherent policies on any major issue and their only platform is to run out the clock on the Obama administration and hope against hope they can beat Hillary Clinton in 2016. Amazingly enough, if it weren’t for their propensity to commit ritual suicide in close elections, the Republicans would already hold the Senate majority, in all likelihood.

To a large extent, the predictions of a GOPocalypse that’s coming someday soon but not right now are based on observable political and demographic factors I don’t need to explore at any length here. As John Judis and Ruy Teixeira argued 12 years ago in “The Emerging Democratic Majority,” long-term shifts in the American population, as the country grows steadily more diverse and more metropolitan, would seem to favor the Democrats. And there’s no question that the Republican Party of 2014 is a peculiar coalition of groups with distinct worldviews and ideologies that don’t always overlap: The corporate overlords and 1-percenters, the burn-it-down Tea Partyers, the decaying but still vocal “Christian conservatives” and the Ayn Rand libertarians are united only by a strident rhetoric of American exceptionalism, a professed dislike of big government, and by what we might call the identity politics of whiteness. They can all agree that they hate Obamacare (for varying reasons) and view the presidency of its author as a continuing nightmare. But they disagree about almost everything else.

Another factor in forecasting Republican doom, I think, is the dim historical sense that political parties are not necessarily permanent phenomena, and that we’ve had various permutations of a two-party system throughout American history. Four American presidents belonged to the Whig Party — actually, the number is six if you count Abraham Lincoln and Rutherford B. Hayes, who were prominent Whigs before they became Republicans — and that’s been gone for more than 150 years. The Federalist Party, our nation’s very first, barely limped into the 19th century and was dissolved in 1824. What historians now call the Democratic-Republican Party (technically an ancestor to both of today’s major parties) dominated national politics for more than 20 years and then abruptly split apart. Couldn’t some version of what happened to them happen to today’s Republican Party?

I think it’s pretty obvious that the answer is no, or maybe no with an asterisk. But history still has some interesting lessons to offer in this regard. The facetious explanation for why it can’t happen is also partly a true answer: The Whigs and the Federalists never had a website. They didn’t spend millions of dollars a year on branding and consultants; they didn’t have thousands of employees, and millions of volunteers, who were deeply committed to their party’s name, heritage, symbolism and mythology.

Generally speaking, political parties die when they suffer an abrupt and massive loss of popular support (which was what was happened to the Federalists), or become divided and paralyzed by issue they can’t resolve. That’s what befell the Whigs, in most respects a liberal, modernizing, reform-minded party that could never decide what position to take on slavery. Today’s Republicans, you might say, face both dangers in the long term, having decisively lost two consecutive presidential elections and facing a mine-studded landscape of contentious issues they’d rather not deal with, including women’s reproductive rights, same-sex marriage, marijuana legalization and (especially) immigration reform.

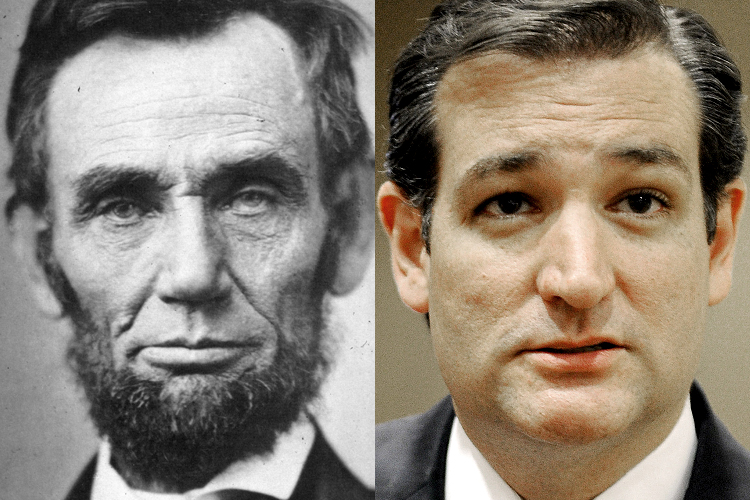

But I don’t believe either of today’s parties is likely to break up or fade away, 19th-century style. Every few years someone makes a semi-serious effort to launch a new political party of the right or left or center — from Henry Wallace to George Wallace, Ross Perot to Ralph Nader — and they always end up disappearing or being absorbed. The two-party system is baked into American politics at this point, but just because the two parties have familiar names doesn’t mean they’re always the same thing. You don’t have to have a political science degree to understand that today’s Republican Party has nothing in common with the one that nominated Lincoln in 1860, and very little in common with the one that nominated Dwight Eisenhower in 1952. Intra-Republican discord does suggest the birth of a possible new alignment in American politics, which may someday be called the “Seventh Party System.”

While not all historians agree about this (since their job is to disagree about things), there’s a commonly used division of American political history into five or six distinct periods. The First Party System prevailed from the birth of partisan politics in the new republic, around 1792, and lasted less than 30 years. As distant as the conflict between Alexander Hamilton’s Federalists and the opposition led by Thomas Jefferson (usually called the Republicans at the time) now seems, many of the issues sound familiar. The Federalists, based in New England, favored a strong executive, a strong central government and especially a central bank and a national economic policy. The Jeffersonian Republicans, while they claimed to identify with the ideals of the French Revolution, had their roots in the plantation South, favored an extremely limited central government and a literal-minded reading of the Constitution, and presented themselves as apostles of individual freedom (as long as those individuals were propertied white men). Set aside your prejudices about Hamilton as a right-winger and Jefferson as the father of democracy and those sound a heck of a lot like today’s Democrats and Republicans, respectively.

As the Federalists shrank to a regional party in Connecticut and Delaware and then disappeared, Jefferson’s ruling Democratic-Republican Party split into various factions, especially after the disputed election of 1824 — the last one conducted without competing political parties — was settled by a highly dubious bargain in the House of Representatives. The Second Party System, which lasted almost up to the Civil War, involved close combat between the aforementioned Whigs and Andrew Jackson’s newborn Democratic Party, technically the same one that exists today. Despite what you may have heard in school about “Jacksonian democracy,” it’s not a legacy to be proud of: It was a party of open racism and open corruption, built on a superstitious white-male populism, antediluvian economic policy and a mistrust of big-city Eastern elites. There’s more than a little Andrew Jackson in Sarah Palin; he’d be a Tea Party hero today.

The Whigs’ implosion over slavery led to the Third Party System, a period of enormous change that led to the doorstep of the 20th century and was dominated by the legacy of one man. Former Illinois Whig leader Abraham Lincoln became the brand-new Republican Party’s first president and then, of course, the party’s guiding martyr. The Democrats, of course, had no division over slavery: They were for it. Most elections of this period were evenly matched, but the Republicans were able to present themselves as the party that had saved the nation, freed the slaves and adopted many Whig-like reform policies: They supported a strong central government, public schools and land-grant colleges, homestead acts, railroad building and so on. At this stage, it’s the Democrats who inherit the incoherent Jefferson-Jackson anti-elite movement, and who represent an unstable coalition of Southern whites and Catholic immigrants in the Northern cities, united only by their sense of grievance.

Next comes the Fourth Party System, which was still largely dominated by the Republicans but much more difficult to summarize. This period covers the Spanish-American War and World War I, the Progressive Movement and the beginning of the Great Depression. It brought women the vote for the first time, a political sea change whose ramifications continue to unfurl a century later. It also marked the moment when activist progressives like Teddy Roosevelt and Bob LaFollette quit the Republican Party in favor of various ill-fated third-party efforts, leaving the GOP firmly under the control of pro-business, low-tax, anti-regulation conservatives. Although the Democrats still represented the white supremacist movement in the South, the party’s base shifted significantly northward. Faced with the growth of socialism and anarchism, Democratic populism was forced to adopt a more urban and activist orientation. There’s no way to encapsulate all the changes in American society during that period, but in terms of political-party history, those were biggies.

Before we get to where we are now, we go through the more familiar-looking territory of the Fifth Party System, when Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal coalition made the suddenly reinvigorated Democratic Party the dominant force in national politics for more than 30 years. Discredited by the calamity of the Great Depression, the Republicans remained in the electoral doghouse (except for the almost nonpartisan choice of Eisenhower) until the fluky and traumatic election of 1968, possibly the most discussed year of the 20th century. That was when Pat Buchanan’s “Southern strategy” succeeded in peeling large numbers of Southern whites, presumably traumatized by civil-rights legislation, away from the Democrats for the first time in American history.

There’s no clear consensus about where the Fifth Party System ends and the Sixth begins, but surely the turning point lies between Nixon’s victory in 1968 and its even more spectacular sequel, the Reagan revolution of 1980. Among other things, that was the moment at which the remaining Northeastern liberals in the Republican Party were conclusively defeated, and ultimately driven out. If Andrew Jackson’s ghost was purged from the Democratic Party within the Fifth Party System, Teddy Roosevelt’s was purged from the GOP in the Sixth. While it’s true that the Democrats remain rooted in big cities and the Republicans in exurban regions, over the course of six or seven decades the two parties swapped demographics and positions to a not-insignificant degree.

To most scholars, though, the Sixth Party System is an era of conservative ascendancy and triumph, the age of neoliberal economics and neoconservative foreign policy, of Newt Gingrich and Rush Limbaugh. It seems axiomatic to me that after Obama’s two presidential victories — elections the Republicans were startled to lose so badly — we are either already in a new era or right on the edge of one. Just to take a wild guess, the Seventh Party System looks like an era of permanent gridlock and overheated rhetoric, one in which the genuine policy differences between the parties are minor (since both serve the interests of different elite sectors) but the symbolic differences enormous. It looks like an era in which the Republicans have lost the ability to compete in national elections, but cling to a share of power as a backward-looking regional white-rights movement whose only agenda is to gum up the works and foment outrage. It looks, in other words, like a tedious slog, one that’s likely to drag on for years until something else happens. But I guess the historians will have to tell us for sure.