Warm weather thousands of miles away would seem an unlikely cause of the United Kingdom’s freakishly wet winter or the bone-deep chill experienced this year by the eastern United States. But a warming Arctic can be blamed for both, said Rutgers University atmospheric scientist Jennifer Francis at the recent AAAS Annual Meeting in Chicago, Illinois.

Warm weather thousands of miles away would seem an unlikely cause of the United Kingdom’s freakishly wet winter or the bone-deep chill experienced this year by the eastern United States. But a warming Arctic can be blamed for both, said Rutgers University atmospheric scientist Jennifer Francis at the recent AAAS Annual Meeting in Chicago, Illinois.

“It’s because the pattern this winter has been basically stuck in once place ever since early December,” Francis said. And the pattern—which has included cold, cold temperatures in the eastern United States, for instance—has been stuck because of the Arctic.

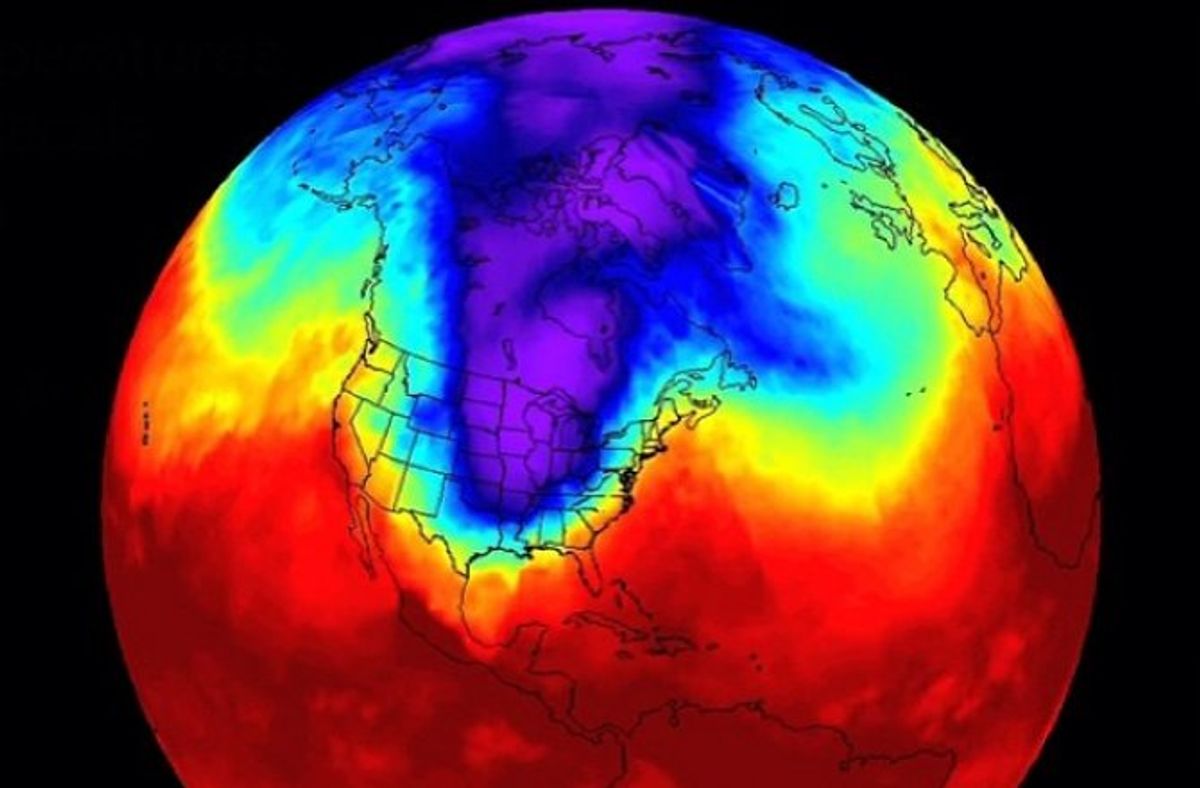

Back in 1896, the Swedish physicist Svante Arrhenius first calculated [pdf] how pumping carbon dioxide into the atmosphere would warm the planet through the greenhouse effect. That warming, he wrote, would be most pronounced in the Arctic regions, a phenomenon known as Arctic (or polar) amplification. And it is now able to be seen above the noise of the world's weather—below is a NASA animation of temperature differences compared to averages, from 1950 through 2013:

The recent amp up of Arctic warming is readily seen by the loss of summer sea ice in the Arctic Ocean. The extent of summer sea ice, in particular, has been on the decline for more than two decades, and the loss of old, thick ice has been especially pronounced (see video below).

“When you’re losing the sea ice, Arctic amplification is certainly here,” said Mark Serreze, director of the National Snow and Ice Data Center. Losing that sea ice, he said, will have impacts in the mid-latitudes, particularly on weather patterns.

The Arctic affects the rest of the planet in many ways, but the one that’s most relevant for Francis’ work is called the poleward temperature gradient—that’s the difference in temperature between the Arctic and the mid-latitudes, where the continental United States sits. That poleward temperature gradient causes air to start flowing from the North Pole southward, and a spinning Earth forces the air to move from west to east, creating the jet stream.

Frequent fliers will recognize the jet stream as the river of air that can give their airplane a boost when flying from Los Angeles to New York City. Weather fanatics, though, might be more familiar with the air pattern for its ability to move weather systems across the continent.

“When you warm the Arctic more rapidly, you’re decreasing the difference in temperature between the Arctic and the areas farther south,” and that’s weakening the poleward temperature gradient, Francis explained. A weaker gradient makes for a weaker jet stream.

“As we weaken this difference in temperature between the Arctic and the mid-latitudes, we expect those winds from west to east to get weaker,” Francis said. “When that happens, we also expect to see that flow in the upper-level jet stream to become more wavy.” Francis compared the jet stream to a river. When a river flows down a steep mountainside, it flows quickly and its path is straight. But when the river flows over a flat plain, it’s slower and its path can begin to wander. The jet stream now sometimes meanders like that slow-moving river:

Read the rest at Smithsonian.com.

Shares