Human beings have always dreamed of flight, the legendary Italian aeronautical engineer Gianni Caproni tells his young Japanese protégé in Hayao Miyazaki’s elegiac and subtle farewell to filmmaking, “The Wind Rises.” But the dream is cursed: Flying machines will inevitably be used, Caproni says, to wage war and slaughter the innocent. Still, he says, he’d rather live in a world with pyramids. The metaphor is not explained, but like so much else in “The Wind Rises,” its meaning lies just below the surface: Every human endeavor on a large scale is compromised, and no one’s hands are clean. The greatest wonders of the ancient world were built by slaves, to honor tyrants.

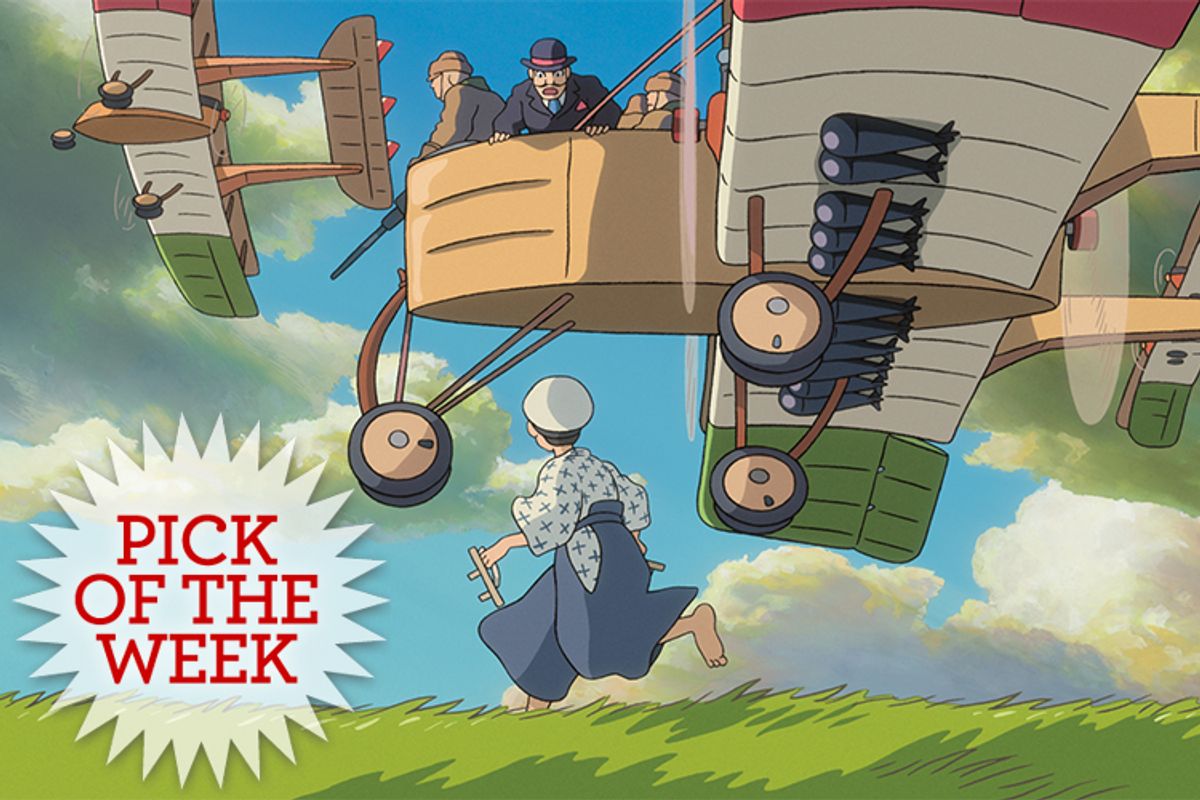

Caproni’s soliloquy on the nature of dreams itself occurs in one of several haunting dream sequences in the film, one that finds Caproni (voiced by Stanley Tucci in the English-language version) and young Jiro Horikoshi (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) surveying the world from the uppermost wing of a huge and fanciful triplane. Some people may wish to describe “The Wind Rises” as a restrained or realistic work because it takes place in a recognizable facsimile of 20th-century Japan, rather than a fairy tale landscape or the mythological past, as in “Spirited Away” or “Princess Mononoke” or “My Neighbor Totoro.” But not me. This Oscar-nominated animated film, which Miyazaki has said will be his last as a director, is a work of immense mystery and strangeness, loaded with unforgettable images, spectacular sweeps of color and nested, hidden meanings. It feels to me like a meditative epic about Japan’s traumatic journey into modernity, and a complicated allegory about the innocence, arrogance and culpability of artists. It’s one of the most beautiful animated films ever made, and something close to a masterpiece.

There’s a certain amount of controversy surrounding “The Wind Rises,” which is based in large part on the life story of the real Jiro Horikoshi, designer of the notorious but magnificent Mitsubishi Zero, the lightweight and highly maneuverable fighter plane that enabled many Japanese victories early in World War II (including, of course, the attack on Pearl Harbor). Honestly, though, most of the controversy has come from right-wingers in Japan, who have accused Miyazaki of being insufficiently patriotic for depicting Horikoshi as a man plagued by doubts and apocalyptic premonitions. I’m not quite sure how anyone in the West could see this movie and believe that Miyazaki (a well-known pacifist) is trying to whitewash Japanese war crimes or duck the question of individual guilt. Arguably the question of individual guilt is the movie’s primary subject, or one of them. While Caproni — who also built planes for a fascist government — assures Horikoshi in one of their dream-meetings that airplanes are not instruments of war or ways of making money but “beautiful dreams,” the film’s constant thrum of death-haunted subtext suggests that Miyazaki does not find this sufficient.

While the phantasmagorical encounters between Caproni and Horikoshi (as far as I know they never met in life) are central to understanding this film, and feature its most breathtaking animated landscapes, they aren’t the only aspects of the story that feel like dreams. Miyazaki takes us back and forth between the bucolic, agrarian Japan into which young Jiro is born and the more urbanized and modern landscape his work gradually makes possible, or at least symbolizes. When Jiro goes to work at Mitsubishi in the late 1920s, teams of oxen are still required to haul aircraft prototypes to the airfield, and Japanese engineers have a reputation as second-rate copycats. When Jiro is sent to Germany in the ’30s to study at the Junkers factory, he doesn’t understand the nature of the society he sees there, or the character of the partnership between his own country and that one. He prefers to focus on the strains of Schubert’s “Winterreise” coming from an open window, and not on the boy being chased through the streets for unclear reasons.

While Miyazaki is the most famous of all Japanese animators, and his art and craft are on full display here, he may not get enough credit as an ingenious storyteller, who builds a narrative through hints and inferences and echoes. Jiro’s dreamlike voyage to Germany is echoed later by an encounter with a German tourist in Japan (voiced perfectly by Werner Herzog in the English version), who politely makes clear that Jiro is ignoring the consequences of his work — a brutal invasion of China, a puppet regime in Manchuria — and predicts that both their nations will be destroyed. As a young man, Jiro performs a life-altering act of kindness during the Great Kanto earthquake of 1923, one of history’s worst natural disasters, which is unmistakably presented here as a premonitory vision of the destruction that will be visited upon Japan in 1945. Indeed, a deeper parallel may be at work, in that Jiro’s willful naiveté resembles that of the physicists who split the atom — they knew what that discovery would lead to, but also believed it was important in its own terms.

Indeed, I suspect there’s a note of covert artistic autobiography in “The Wind Rises,” whose title refers to a famous line by French poet Paul Valéry, contemplating a graveyard by the sea: “Le vent se lève! … il faut tenter de vivre!” (“The wind is rising! We must try to live!”) I don’t mean that Miyazaki fears his art has been perverted to evil purposes, or anything as blunt as that. It’s more that Miyazaki too has pursued his dreams without thought of consequence, himself fueling a change in the world around him that he doesn’t quite understand. He gives us Jiro as a pure-hearted genius by day, full of love and innocence, and a dark dreamer at night, sending his airplanes out by the thousands to destroy and be destroyed. On the one hand: “Isn’t this lovely?” On the other: “Watch out for what lies below.” Those are the messages Miyazaki has sent us all along, and this tender, ambiguous fable makes the perfect farewell.

"The Wind Rises" is now playing nationwide.

Shares