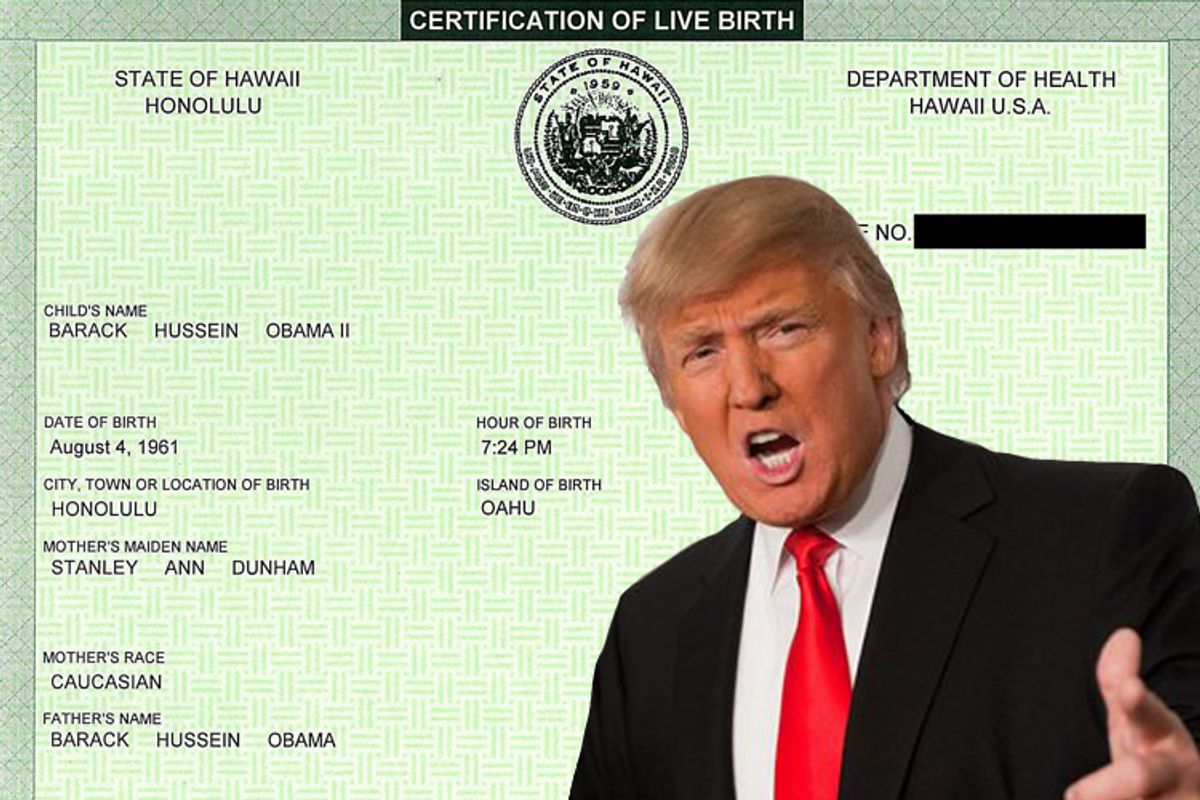

From the steady roll of theories on what happened to Malaysian Arlines Flight 370, to Sarah Palin's "death panels" panic, to Donald Trump's birther theories, misinformation spreads like wildfire in the age of Facebook.

In 2013, professor Walter Quattrociocchi of Northeastern University along with his team studied how more than 1 million Facebook users engaged with political information during the Italian election. During that election a post appeared titled: “Italian Senate voted and accepted (257 in favor and 165 abstentions) a law proposed by Senator Cirenga to provide policy makers with €134 billion Euros to find jobs in the event of electoral defeat.”

The post was from an Italian site that parodies the news. According to MIT Technology Review it was filled with at least four major inaccuracies: "[T]he senator involved is fictitious, the total number of votes is higher than is possible in Italian politics, the amount of money involved is more than 10% of Italian GDP and the law itself is an invention."

Despite the blatant falsehoods of this parody news post, the story went viral -- shared over 35,000 times in less than a month. This, of course, wasn't the worst of it. The post was then picked up by a political commentary page, which gave the falsehoods perceived credibility. MIT Technology Review explains the scary outcome, "Today, this 'law' is commonly cited as evidence of corruption in Italian politics by protesters in cities all over Italy." This is the equivalent of an article from the Onion being treated as credible news (which happens surprisingly regularly).

In order to study how instances of conspiracy theories, like the one above, happen, the team led by Quattrociocchi looked at both mainstream media posts, and those from alternative news media. They looked at how people engaged with these posts including "likes" and comments. They found that people engaged for the same amount of time on both mainstream and alternative news posts. However, people were more likely to engage with posts that were known to be false -- either parodies, or posted by trolls.

Those who engaged with false information posted by trolls were more often readers of alternative news -- or as the study says, those who do not trust mainstream sources. According to MIT Technology Review:

"This suggests an interesting mechanism for the emergence of conspiracy theories. Conspiracy theories seem to come about by a process in which ordinary satirical commentary or obviously false content somehow jumps the credulity barrier. And that seems happen through groups of people who deliberately expose themselves to alternative sources of news."

These results are only from Italy, where mainstream media is influenced by politicians. Newseum in Washington, D.C., ranks it only as "partly free" press, which might be why people turn to alternative press. It seems that one way conspiracy theories form and spread on Facebook is when false information is given the slightest bit of credibility.

Shares