I am going through a box of letters written to my father, the critic John Leonard, sifting through his memories before they are shipped off to an archive at Boston University. Here's one from Hunter S. Thompson, exactly the kind of crazed scrawl you'd expect from the original gonzo journalist. There's a handful from best buddy Kurt Vonnegut. Heartfelt thank-yous from Carly Simon, Edward Said and Jan Wenner. An importunate note from National Review's Bill Buckley, asking for some help promoting his novel. It's all fascinating and all impossibly archaic. People just don't do this anymore. If you're lucky, they'll dash off an email. They're more likely to favorite your tweet and be done with it. These letters might as well have been written in cuneiform. They have weight.

But I'm looking for a specific document, something that won't end up in the BU archive, something I intend to keep in my own treasure chest: a letter Bill Gates wrote to my father nearly 20 years ago, explaining why he got me fired from a job.

The missive in question was a response to a television appearance my dad had made a few weeks prior, in which -- roaring like a mama grizzly guarding her cubs -- he all but challenged the CEO of Microsoft to a fight. Gates hadn't bothered to personally contact me about my transgressions, but when slapped by a white glove on "CBS Sunday Morning," he took notice.

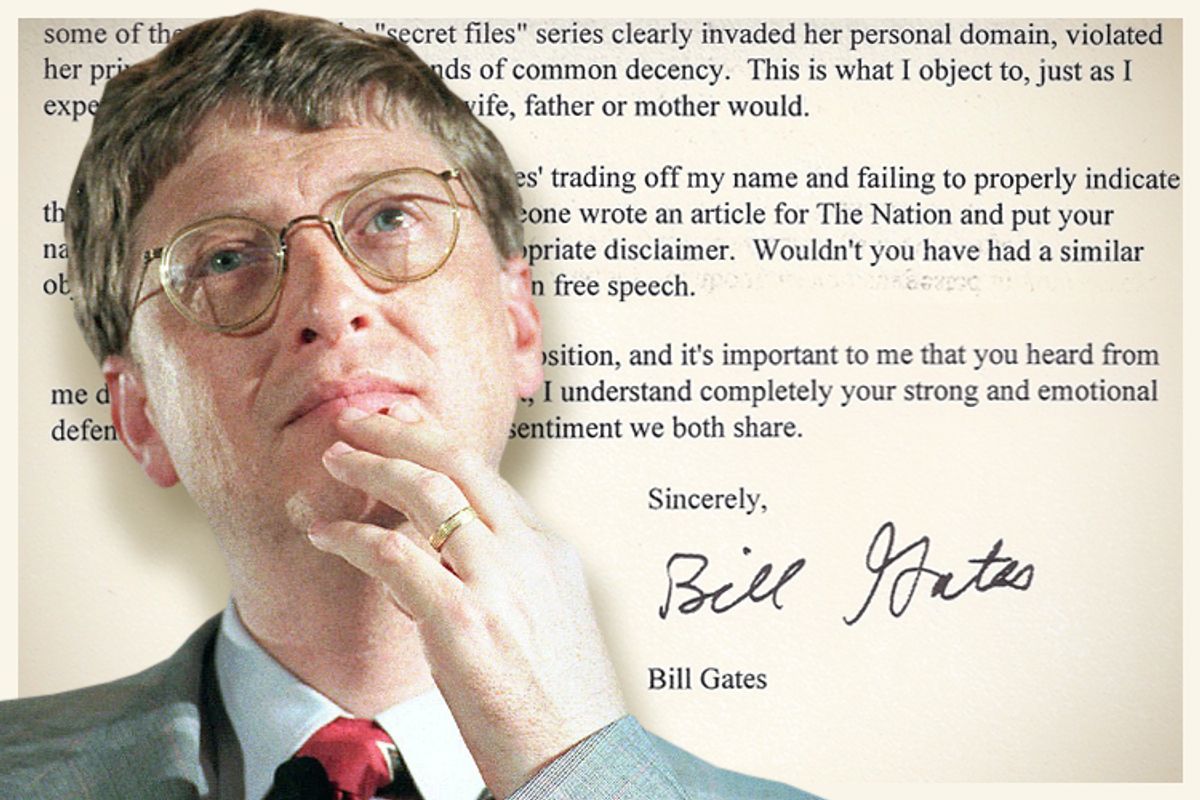

And there it is! A two-pager, written on his personal stationery, complete with his signature and a polite, but firm, declaration that he, Bill Gates, had just been trying to protect his family. Attacking Microsoft or Gates himself was fair game, explained the billionaire, but I had violated Melinda Gates' privacy "and crossed the bounds of common decency." Such was cause to let slip the dogs of war. (Or personal lawyers, as it were.)

I posted a pic of Gates' signature on Facebook, and caused a mild hubbub among friends and followers. My daughter, a college sophomore, expressed agitation. Wait, what? She'd never heard this story! That, in turn, took me aback. How was her ignorance possible? I used to dine out on the story of how Bill Gates got me fired! But it had happened so long ago my own children didn't know about it? Unconscionable! I mentioned the affair to my editors at Salon, and it was quickly decided: In the interest of history, and perhaps a few weightless retweets and Facebook shares, the full story must be told, again!

* * *

Christmas, 1995. I am a hustling freelancer, working for anyone who will pay me to write about "The Internet." My wife is in graduate school, my baby daughter is a year old, and I've got bills to pay. I'm not turning down any work. When New Line Television approached me to ask if I was interested in contributing to a new joint venture the company was starting up with America Online called "the Hub," I didn't think twice. Before they even explained that my "channel" would be a weekly satirical serial called "The Secret Files of Bill Gates," I was on board.

The concept was simple -- even, well, sophomoric. I was a hacker who had infiltrated Microsoft. Each week, I would riff on some new thing I'd found in the bowels of cyberspace. For example, I intercepted Bill Gates' emails with the chairman of the Chinese Communist Party, Jiang Zemin, in which, among other things, Gates asked for advice on how to deal with anti-Microsoft press coverage. ("Dissent," Gates was told, "usually boils down to a failure of marketing.") Another concerned Microsoft's demands that its new partner NBC include references to Microsoft's products in its Thursday night sitcom lineup. (Like, how crazy was that idea? Ridiculous. Can't imagine anything like that ever happening! ) My last -- never published -- installment had Bill Gates ordering Michael Kinsley, the publisher of Microsoft's new Web magazine, Slate, to publish his poetry.

And so on.

In 1995, AOL's move into content constituted big news. The old-schoolers and college kids may have sneered at AOL.com email addresses, but never you mind, America Online was indeed where the majority of Americans got online. The company was growing at incredible speed. The future of journalism? AOL seemed as good a place as any for us to figure out what that looked like.

But Microsoft, in 1995, was still the mightiest of them all. Slow to appreciate the promise of the Internet, to be sure, but few among us foresaw a future in which Microsoft would become effectively irrelevant. Instead, we felt foreboding -- it was only a matter of time before Microsoft ruled all of cyberspace. In the 1990s Microsoft routinely crushed competitors with a single glance. The rollout of Windows 95 was a major cultural event. For AOL to go out of its way to tweak Bill Gates, when Microsoft was a huge advertiser on AOL, seemed a little impertinent -- cheeky enough to attract the attention of the Wall Street Journal, even.

Not long after the news of the Hub's launch, my Christmas break in Florida was interrupted by a WSJ reporter. He wanted to know what would happen when Microsoft's lawyers came calling.

Funny, I had asked my New Line bosses exactly the same question. And they'd told me something to the effect of, "Oh, we've got lawyers too. Don't worry about it." I cavalierly repeated this assurance to the WSJ reporter. Whatever. COME AT ME, BRO!

My channel launched in March. Six weeks in, I happened across a news report recounting the courtship between Bill and Melinda: The story went that Bill was always traveling -- consolidating his company's control over the the computing universe with relentless energy -- but they'd still make an effort to connect. They would even go to the same movie while in different cities, after checking to make sure the showtimes were similar. Very cute. Nerdily romantic, even.

So I mocked it. My fictional hacker discovered a chat transcript between Melinda and Bill Gates, celebrating the anniversary of the first such "movie date." Only, Bill wasn't really there! He'd sent BillBot in his place. The conversation didn't go well. Artificial intelligence still had its bugs.

An excerpt:

mg: i knew you wouldn't remember, you big lug. i don't know why everyone thinks you're so smart. we saw Bride of Killer Nerd. and you said it wasn't as good as the first one, Killer Nerd. but it was still funny.

billg: please do not call me a nerd. i am not a nerd.

mg: not any more dear, not any more. rich people aren't considered nerds.

billg: i am a rich people.

mg: you mean, we are rich people, right. ha ha. so where are you now?

billg: i am in a united airlines 767, approximately 20000 feet above topeka, kansas. piloted by neil o'malley. today's movie is The Net. please put your seatbacks and tables in their full, upright position. where are you?

mg: oh, I'm just sitting at my desk, looking at the sales reports for Bob.

billg: Bob is a good friend of mine. i like Bob.

mg: yeah... right. bill, are you ok? you sound kind of strange.

billg: sound? this chat room is not sound-enabled. you are incorrect.

mg: fine. You're TYPING kind of strange. what's wrong? did the deal with Time-Warner go sour? I heard a rumor netscape was involved.

billg: "netscape" is a forbidden word. please do not use it again or your chat room privileges will be cancelled.

mg: Huh? don't use that tone of voice with ME, mr. "i am rich people" gates. or you might as well turn that plane right around.

And so on. Melinda's furious discovery that her husband has sent a bot in his stead is followed by an email exchange between Gates and one of his top executives, Brad Silverberg. Bill wants an improved BillBot 2.0, and he wants it now.

In retrospect, I don't think I can cite the Melinda Gates episode of "The Secret Files of Bill Gates" as one of my greatest literary triumphs. I'm ashamed to say that it's the only episode that didn't include even the slightest whiff of a critique of capitalism, and yet it's the one that got me in trouble. Melinda Gates proved to be my Rubicon. The die was cast. Bill Gates' personal lawyers sent the Hub a letter. I was let go less than 24 hours after the receipt, via a voice mail.

The voice mail said that the action was a direct response to the legal letter, but a few hours later I was told that my channel "had been underperforming."

I did not waste one second. After listening to the message, I called the Wall Street Journal reporter who had interviewed me a few months before. "Hey, remember when you asked me what would happen when Bill Gates' lawyers came a-calling? Guess what!" I mouthed off on The Well, and my friend Scott Rosenberg wrote a news item about the affair for a newly formed "Web magazine" called Salon.com. I appeared on CNNfn, looking absurd in a button-down collarless shirt. I made as much hay as I could. As far as I was concerned, getting fired by Bill Gates was the best thing that could happen to a hustling freelancer. I was going to take my 15 minutes of fame to the bank.

However, I did not expect that my father would decide, a few weeks later, to use the five minutes of media criticism he was allotted on "CBS Sunday Morning" to take personal issue with Bill Gates' professional assault on someone who "looked, in fact, remarkably like the father of my only grandchild."

And I certainly wasn't prepared for the full-throated finish.

To Michael Kinsley, I say, 'Watch out.' Microsoft, America Online and the other cyberspace cadets who promised to revolutionize journalism with glitzy online magazines will behave just as badly as thin-skinned old press barons like William Randolph Hearst.

And to Bill Gates, I issue a warning: 'Mess with my family and I'm unamused.' Andrew was gentle. You haven't seen truly savage satire yet.

Which led, a few weeks later, to "The Letter." (Which you can find in full at the bottom of this article.)

Some excerpts:

It has been brought to my attention that your CBS Sunday Morning essay last week concerned the matter of AOL's web magazine, The Hub, and my objections to a "Secret Files of Bill Gates" series pretending to be my email downloaded by a hacker. I have since read the transcript of your essay and I wanted very much to write and make clear my views on this topic...

My objections to the series are very specific and not in any way aimed at the author's right to express himself freely online or anywhere else. I have strongly and publicly supported freedom of speech on the Internet, and I hold the idea of protecting the First Amendment very dear. Online speech must remain just as free and open as any other medium if the Internet is to flourish and society is to benefit from its enormous potential....

Rather, this issue is about something that, considering your defense of your son on Sunday, I'm sure you can understand. It's about my wife Melinda, her right to privacy and her wish to be treated with the common decency any ordinary person would expect. Melinda is not a public figure, and she has made a serious and sustained effort to maintain her private status and live as normally as possible given my notoriety. Without question, certain aspects of her life are newsworthy and could be construed as falling with then "public" domain. But some of the content in the "secret files" series clearly invaderd her personal domain, violated her privacy and crossed the bounds of common decency. This is what I object to, just as I expect you or any other husband, wife, father or mother would....

I do hope you can understand my position, and it's import to me that you hear from me directly on this matter. For my part, I understand completely your strong and emotional defense of your son and family. It's a sentiment we both share.

A few years later, I tried to parlay this exchange into an interview with Bill Gates on the topic of Microsoft and open-source software. We know each other from way back, I told Microsoft's top P.R. guy. Sadly, Bill declined.

And there you have it. The rest of the '90s were pretty busy for reporters who covered "the Internet," which might explain why, by the time my children were old enough to comprehend my boasting, I couldn't remember as far back as those halcyon days.

Reviewing the archives -- the hard copy of the letter, a DVD of my father's "CBS Sunday Morning" appearance, even the digital file of my Hub episode, with its quaint truncated file name "BILLBOT" -- I am compelled to wonder how this drama would have played out in our current world of social media.

How viral would the mano-a-mano challenge from my father to Gates have gone? How many obnoxious tweets would have mocked, say, my clothes? How many toxic flame wars would have broken over the fact that my father dissed postmodernism repeatedly in the segment involving me? (He somehow managed to weave the epic hoaxing of Social Text by Alan Sokal into the Gates affair.) Hell, would his lawyers even have been summoned from their lairs, in the current anything-goes climate of cyber-cacophony? Surely, the Onion has run countless stories more obstreperous than anything I ever came up with.

Reconsidering the the day Bill Gates got me fired, what strikes me most is how seriously we all took our words, back then. Today we spill them across cyberspace like chaff in a ticker-tape parade, unable to remember what we tweeted about last week, much less 20 years ago. In retrospect, I've got to give Bill Gates a lot of credit for taking both my words and my father's so seriously, and taking the time to write a letter. Twenty years later, it seems to mean something more now than it did then.

Click below to read the full contents of Gates' letter:

Shares