One hundred and seventy-six missing, 14 confirmed dead. Out West, we always assumed the end might be near. We still imagined ourselves frontiersmen, despite the connectedness of 2014. Part of why we lived there was because we liked to be close to the elements, close to nature. Nature, of course, can be destructive as well as beautiful. I don't know whether this fact, the constant possibility of terror, of mud flowing through everything and everyone you know, is part of what made my home beautiful, but it hardly seems to matter anyway, not today.

Because on Saturday night, the day of the slide, voices were heard calling for help, but it was too dangerous to even attempt to go in after them.

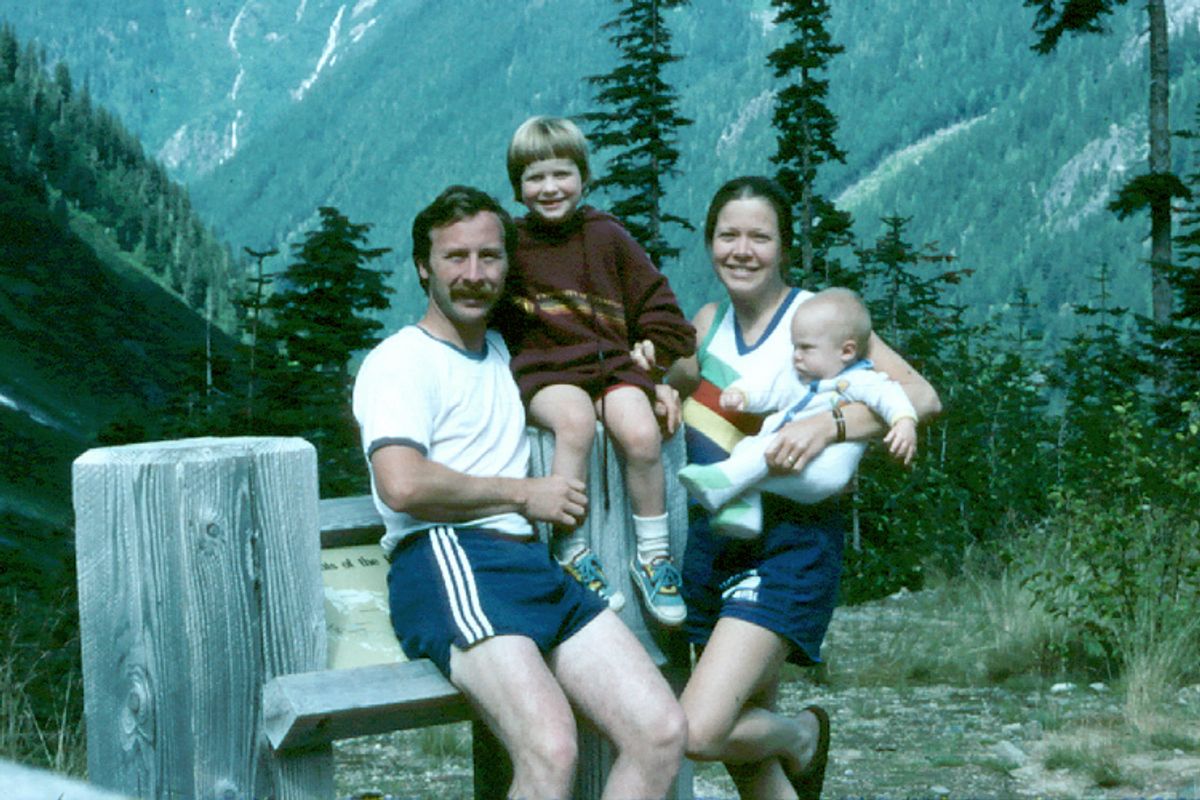

Part of why we lived out there was because we never figured our tragedies would be big enough to make the national news. When I was born, my parents lived in Darrington, now nearly cut off from the rest of the world, right there under those mountains. I was raised in Arlington. But back then, we lived in a rented house that felt like it had no insulation, and we heated that house with a wood-burning stove. On the day I was born, my dad was out in the forest chopping wood to heat the house, and so my mom was rushed down 530, a road that is now no longer a road, to the hospital in Arlington, where I would end up living, and my dad was still in the forest chopping wood to heat the house, and it was February and so it was almost certainly just above freezing and raining; it just had to be raining that day.

We used to go to a church potluck right there on the North Fork. I never thought anyone who hadn’t grown up back there, back home, would know what the North Fork is. This should not be: that I can simply write "the North Fork" and people will know that I'm talking about the Stilly; that I can write "the Stilly" and people know I am talking about the Stillaguamish. It used to be our secret. Every summer at that potluck we played volleyball in the river. We played volleyball in that river right there on that bend that is no longer a bend. Rivers back home ran cold year round, the flow glacial, after all, and it would only be hot enough outside for a week or two to actually want to go in the water. Every spring the rivers rose with the thaw and flood plains were sunk, every year some folks were underwater, every year sink holes and mudslides, but never like this.

On Saturday night until 11:30 you could have heard voices calling out from under mud and rubble, apparently, but it was too unstable to risk any more lives. Mud like quicksand. Firefighters sunk to their armpits and pulled back out with ropes. Isn't that how we always knew it would be, back home? Folks trapped inside nature, and nature wouldn't let us get them?

How do I explain it to you? The day after mud crashed through at least six houses and all our lives I was sitting on my couch and writing. That’s how I make sense of things. How odd to have a tragedy hit your small town, your tiny town, while you still sit on your couch in the big city.

I wanted to hear the news. I turned to CNN and figured that human beings trapped under a bunch of mud and water would warrant an update, but no. No, no: There had been some additional speculation about the whereabouts of a plane and apparently that captures the American imagination, apparently missing planes will sell more ad time than our folks, my folks, screaming out from under the mud. I watched Don Lemon and an exchanging roster of experts talk about a plane down for hours, hours on end, with pauses only for ads, repeating the same news. You would think there was no other news. But there was other news. There was my news.

I've traveled to a lot of places in this world -- Madagascar, Goa, the Alps -- but the 20 miles between Oso and Darrington are among the most crazy beautiful in the world. In the summer when the sky would be clear and White Horse and Three Fingers and Pilchuck would glow and turn pink then orange as the sun went down. The fields to the left or right of 530 yellow; the foothills green, always; the peaks still white, and driving with the window down you couldn't help but smile.

Two weeks ago, a residential building blew up in East Harlem and killed people. It was only a couple of blocks from my house. I was out early that morning for a dentist appointment, but my roommate said that it felt like an earthquake. We both said that it could have been us, still sleeping.

And this Saturday, people heard a crack and then a mountain fell down. Saturday, it could have been my mom, my dad, my sister.

Part of our fascination with tragedy, I think, is our own fear, but you probably knew that already. We are obsessed with Flight 370 because we too are afraid of flying off the grid to never be heard from again. It could have been my house that blew up two weeks ago. It could have been my parents buried under that mud. It wasn’t, not this time, but in towns this small with 176 still missing everyone knows somebody who knows somebody; we’re all too close to the tragedy, to the loss.

Small catastrophes happen every day. My grandmother has been dying of cancer for two years. We lose kids every day to disease, to violence. They're all somebody's kid, somebody's grandma. But there is a different feeling to these public moments of shared catastrophe. They feel random, inevitable, so unpredictable. It all feels so unfair. Ironically, the collective suffering can bring us together, if briefly. These moments remind us how close we are to the brink; how technology hasn't yet made nature less violent; how someday it could be us, our mothers, our fathers, our sisters, our sons, our daughters.

For a moment we're all the same.

Shares