It is currently fashionable in Republican circles and in cable TV talk shows to argue that, first, President Obama’s foreign policy projected an aura of weakness, which was then, second, exploited by President Putin with aggressive and illegal moves in Crimea.

It is currently fashionable in Republican circles and in cable TV talk shows to argue that, first, President Obama’s foreign policy projected an aura of weakness, which was then, second, exploited by President Putin with aggressive and illegal moves in Crimea.

The problem with this narrative is that, while convenient, it is also patently untrue. Russia in general and Putin in particular, operate under the power politics rules of international affairs. They will thus act according to perceived threats to the security interests of the Russian state.

Unless President Obama had been willing to use military force, an ill-advised course, there was probably nothing the United States could have done to deter Putin’s actions in Crimea once Ukrainian President Yanokovych was deposed and had departed.

True, President Obama’s sloppiness with his “red line” maneuvers in Syria provided an opening for this charge to be made now.

But as a reality check, ask yourself this question: Assume Obama had used military force to back the red line in Syria, would Putin have acted any differently in Crimea given the perceived threat to Russian bases?

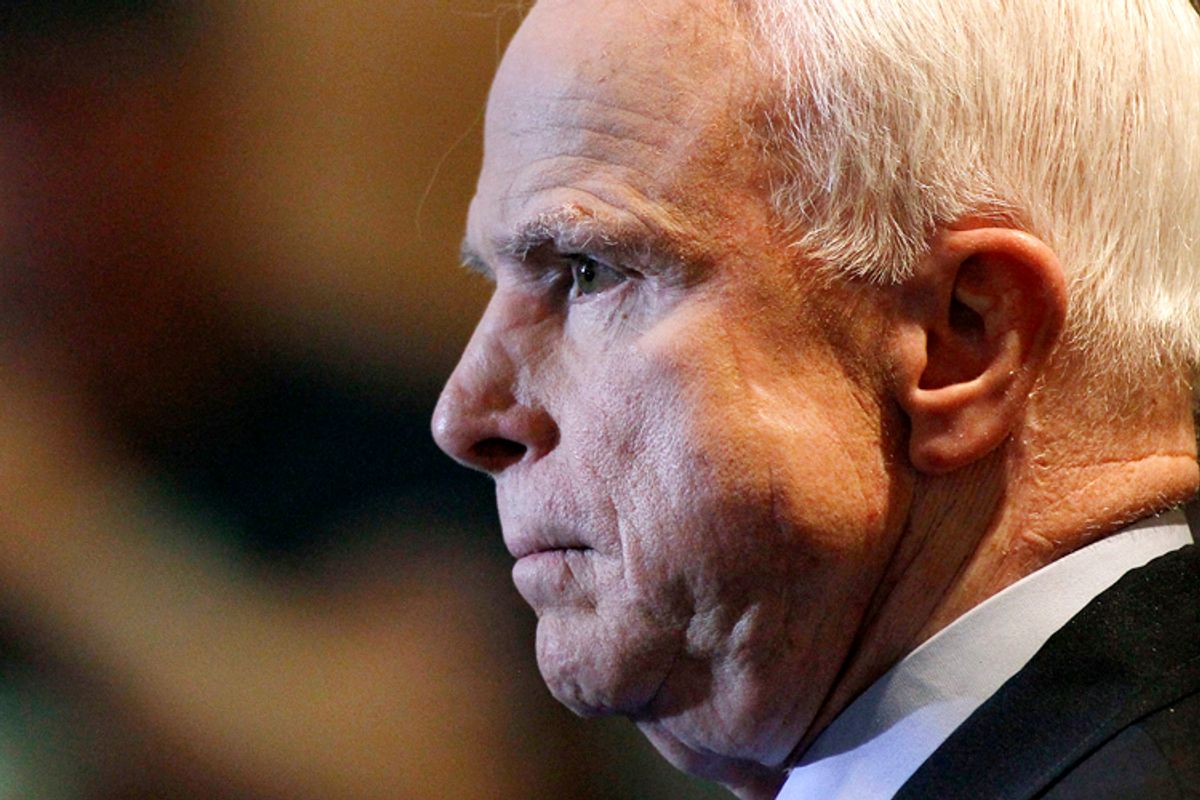

One of America’s most astute foreign-policy minds, Harvard’s Stephen Walt, has criticized the sideline quarterbacks like John McCain and Mitt Romney for “…lambasting Obama for his alleged ‘weakness’ on Ukraine, Syria, Benghazi, or whatever – even though the main complaint seems to be that he isn’t willing to repeat the same costly blunders they either made or supported in the past.”

What if Republicans had been in power?

Let us imagine another world – and go back a few years to 2008 when Bush, Cheney and the neoconservatives were in power. They talked tough and backed it up in Iraq and Afghanistan. They also abrogated the ABM treaty and ramped up defense spending.

Yet, in 2008 the same President Putin who recently sent unmarked troops into Ukraine did something as unsavory. He invaded Georgia to within miles of its capital and recognized the independence of two breakaway Georgia regions.

And yet, the Republicans – with their emphasis on an always muscular foreign policy – stood by relatively idly. Did Republicans think that Putin acted out of anything other than his cold-blooded calculation of Russia’s interest? Or did they believe then that the Bush/Cheney team’s “weakness” invited Putin’s action in Georgia?

No, they didn’t. But evidently, different rules of foreign policy calculations and interpretations apply depending on who’s in office. That may be effective politics, but hardly adds up to a serious policy argument.

Why the U.S. sits on its hands on occasion

There were other incidences of a less than muscular Republican foreign policy in full view of Russian shenanigans. Consider 1981, when the Communist regime in Poland, a Soviet prop, instituted martial law and sent tanks into the streets.

Back then, it was none other than Ronald Reagan who stood guard in Washington against the Evil Empire.

Bottom line: Russia — be it the czar, the Soviets or Putin — will act, regardless of how tough the guy in the White House might be, when they feel that they must secure their vital interests.

That basic truth aside, a good case can actually be made that it was the very muscle flexing that is so often advocated by U.S. neoconservatives that has brought about the unfortunate and dangerous state of affairs we face today.

Clinton was too “conventional” in his foreign policy

And in bringing about this worsening of the global political landscape, the Democrats are by no means without blame. Having won the Cold War, the United States – then under the aegis of President Clinton and Secretary of State Albright — did not give the Russians a framework and path to become integrated into the West.

This failure was all the more stark as it contravened the pivotal U.S. lesson from the mid-20th century, when post-war engagement with defeated Germany and Japan showed positive results. Taking that constructive fork in the road was anything but self-evident, given the torched earth policies of these then fascist powers.

Instead of emphasizing diplomacy through the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, the Clinton Administration opted for a truly bizarre option — emphasizing the expansion of NATO, a military alliance that had been created to counter the by-then defunct Soviet Union.

Favoring U.S. industries, not understanding with Russia

Doing so certainly aided the business prospect of U.S. defense firms in the ensuing decade. And the next move in Clinton’s blow-by-blow strategy — encouraging a pipeline network aimed at undercutting Russian energy firms – had a similar effect. It aided the business prospects of U.S. energy and engineering firms.

Of course, nothing has come of this by now decades-long energy strategy – even though it could come in handy by now. Even eight years of a Big Oil-friendly Republican Administration – often acting in lockstep with the U.S. energy industry’s interests – has not changed that.

The reason why is simple. If one wants to have a real check on Russia, one must focus on changing Russia itself. If, instead, one plays Russia by the same old rules of the game, Russian reflexes will always be in accordance to the inevitable – relying on a somewhat aggressive strategy in its near-abroad as the best defensive option.

Clinton failed to close the deal with Russia

It is not just with the benefit of hindsight that one can argue that the Clinton Administration’s inability to break out of a Cold War mindset was an unfortunate lost opportunity. Worse, it was a clear failure of statesmanship that set U.S.-Russian relations on the wrong course.

The G.W. Bush Administration only made things worse. It adamantly pursued NATO expansion in every corner of the globe that is located next to Russia. And it never ceased to admonish NATO member nations to increase their military budgets, while letting Russia know in no uncertain terms that it could not become a member of NATO.

Talking of “red lines”

The Bush Administration’s push to bring Georgia and Ukraine, both of which had been integral to Russian history, into NATO was actually a point at which the West crossed a red line. One does not have to be a Russophile – and I certainly don’t count myself among the latter – to hold that view.

To understand how this move was seen as a provocation to Russia, one just has to have the human ability to put oneself into somebody else’s shoes – and then also employ just a dose of both fairness and strategy.

After all, Russia’s entire history has been one of invasions. It is not so long ago that it lost over 20 million people in the Second World War.

Shares