Why should we care about Wonder Woman?

It's a question that you'd think a book on Wonder Woman would answer. And yet, Tim Hanley's new "Wonder Woman Unbound" never really does. There's plenty here for Wonder Woman fans; Hanley writes with clarity and enthusiasm, and he's got a fine eye for the goofy absurdities of comic-book narratives, from calculating the relative percentage of panels devoted to bondage in early Wonder Woman comics (short version: a lot) to pointing out that the cannibal clams Wonder Woman periodically encounters aren't actually cannibals, but anthrophages (if they were cannibals, they'd eat other clams, and wouldn't be much of a threat.) Speaking as someone who is personally obsessed with at least some things Wonder Woman, I turned the pages with gusto. But still I kept wondering — if you weren't already invested in the character, why would you read this?

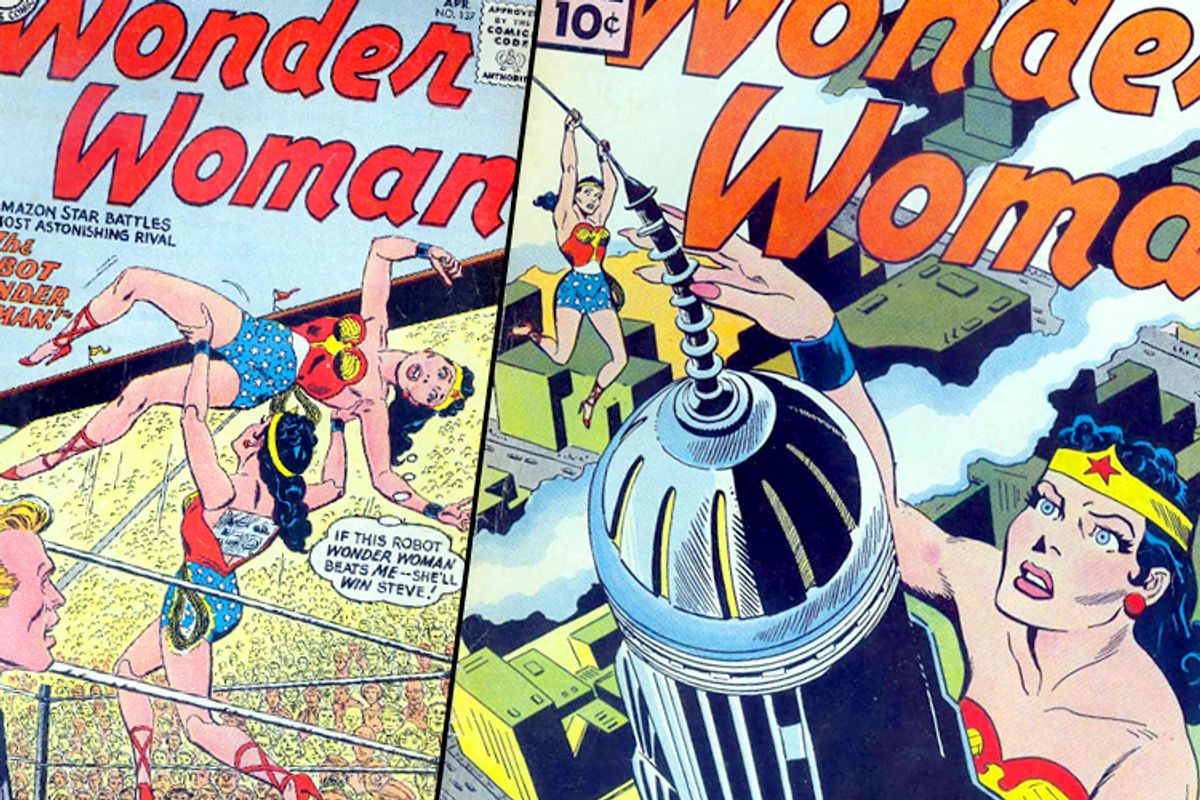

There could be various possible answers to this. You might, for example, make the case that Wonder Woman comics have aesthetic worth — that they are works of art, and are therefore of interest to a wide audience. I actually believe that this is true of the original Wonder Woman comics by William Marston and Harry Peter, which I think are some of the most beautiful, bizarre, outlandish works of art I've ever encountered in any medium.

Hanley, however, explicitly refuses to make that claim. He acknowledges that William Marston used his comics to promote his psychological and gender theories, but Hanley concludes that ultimately the books should just be seen as "adventure stories for kids that presented simple, surface-level messages about a strong and capable heroine." Robert Kanigher, the writer who took over after Marston, doesn't even rise to that level; Hanley argues that he had no sense of continuity and no vision for the book, but simply sat down and typed, churning out nonsensical, repetitive, empty-headed hackwork. Nor does Hanley make any great claims for the Lynda Carter television series. He praises Greg Rucka and Phil Jimenez in passing, but doesn't spend any time analyzing their work or explaining why they might be worth reading. Clearly, for Hanley, Wonder Woman's is interesting for reasons that have nothing to do with the aesthetic merit of the stories she appears in.

Maybe, then, we should care about Wonder Woman because she reflects, or tells us something, about the culture in which she appeared? Hanley does make this argument on a couple of occasions, arguing for example that Wonder Woman's feminism reflected wartime opportunities for women. But as he correctly points out, the character's original conception was extremely idiosyncratic; William Marston believed that women should rule the world by teaching men the joys of loving submission, which meant that his comics were filled with paens to women's strength and images of women tied up. That combination was very popular — Wonder Woman sold hundreds of thousands of issues a month in the 1940s— but the books were so tied to the creator's individual vision that it's hard to relate them to broad social trends beyond Marston's particular crankery.

Moreover, after Marston died in 1947, Wonder Woman's sales plummeted; she became consistently one of DC's least popular books. Nor could you really say that Wonder Woman reflected the changing role of women in any straightforward way. The first issue of Ms. magazine in 1972 featured an image of Wonder Woman, and Steinem created an anthology of Wonder Woman comics with feminist essays included. But the Wonder Woman comics themselves, as Hanley shows, were blandly unfeminist hackwork written by men. As for more recent times, Hanley correctly notes that, "Superhero comics books aren't terribly relevant these days." Moreover, even within the small world of superhero comics fandom, "For the past thirty years, Wonder Woman has been an afterthought." Hanley does provide a fascinating discussion of how Amazonian myths dovetailed with the Ms. magazine circle's theories about originary matriarchies. But that only leaves you saying, why not a book about this in particular, rather than one where you have to spend a bunch of pages telling us the ways in which five decades of Wonder Woman comics were mediocre?

Wonder Woman is, then, in Hanley's view, neither particularly aesthetically worthwhile nor particularly popular nor (except intermittently) relevant. But … she's Wonder Woman. The character is, as Hanley says, "a cultural touchstone," as a symbol of feminism and (though Hanley doesn't really engage with this) as a sex symbol. People recognize her; she has fans. Folks want to read about her and write about her, not because she's art, nor because she's popular, but rather because she means something to them, personally. Gloria Steinem, as Hanley says, had an investment in the Wonder Woman stories of her youth, and that investment had little to do with the actual Marston/Peter comics. Steinem loved the character because she loved the "toe-wriggling pleasure of reading about a woman who was strong, beautiful, courageous and a fighter for social justice." She simply ignored or dismissed the wall-to-wall bondage in those comics, not to mention the virulent racism. She liked Wonder Woman, not so much because of what Wonder Woman was, as because of what she'd decided Wonder Woman would be. It's almost as if she had written her own version of the character, and pledged herself to that. Fandom is built on nostalgia and imagination. You care about Wonder Woman because you care about Wonder Woman. There doesn't have to be another reason.

To some degree, that's kind of exhilarating. Hanley's book is certainly energized by his own love of the character, and it's hard not to be swept along as he follows her through her indifferent adventures, stopping here to talk about how Frederic Wertham's attack on comics ended up providing Batman with a stable love interest, or pausing there to discuss how Tiffany Fallon posed in a Wonder Woman costume for Playboy because she loved Linda Carter. Hanley cares so much, it seems churlish not to care along with him. Love is its own rationale.

At the same time, though, there's something a little depressing about the extent to which that love seems unearned. Whatever you think of the original Wonder Woman stories (and, again, I like them a lot more than Hanley does), at this point she isn't much more than a corporate marketing icon and, perhaps, a nostalgia-tinged memory of a mediocre television show. "She isn't a great character despite her contradictions, but because of them," Hanley declares in his conclusion — but the vast bulk of his book actually suggests that she isn't an especially great character at all, if "great character" means appearing in worthwhile stories or even appealing to large numbers of people. Love can elevate pop culture detritus, but it seems like the bland logic of marketing and pop culture legacy memes can wash out passion as well. "Wonder Woman Unbound" demonstrates how much an engaged author can do with indifferent material. But it also made me wish that we'd demand more from the icons to which we grant our affection.

Shares