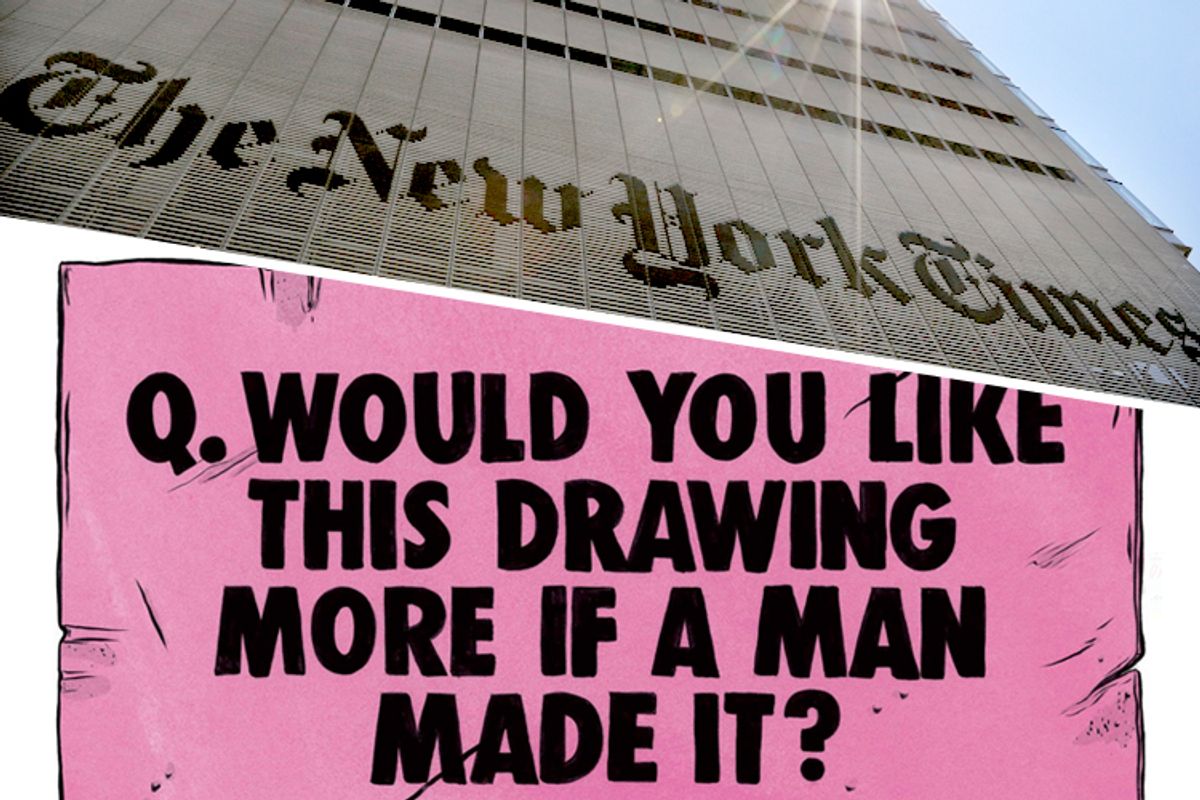

So here's the thing about cover art that proclaims "Q: Would you like this drawing more if a man made it? A: The art world would." When this is the cover of the New York Times Book Review, a publication with its own well-documented issues with reviewing more books by men than women, it makes one turn to the table of contents for a VIDA count.

The results, by my count:

Seven novels are reviewed. Five books were written by men, two by women.

Five nonfiction books reviewed. Three written by men, two by women.

A short list on "rebels and radicals." Four books, all written by men. Ten rebels and radicals mentioned by name, all of them men.

(And a Visuals column that leans male but is harder to quantify.)

So if the question is, Would the New York Times like this book more if a man wrote it?, well, it certainly seems like it would have a better chance of getting reviewed.

But this is Reviewends, a column about how the Times Book Review loves to save all its criticism for (usually) the second-to-last paragraph of a review, only to gently walk part of that critique back in a conclusion that begs, "blurb me on the paperback."

We started chronicling this long-standing pattern last week. Sunday's issue had a couple more classics. Two particularly caught our eye.

Floyd Skloot on "Marshlands" by Matthew Olshan:

The penultimate paragraph critique: "But for all its shocking revelations, the story lacks propulsion, its backward narration and withholding of information distracting us from the action and motivation."

The Reviewend: "Nevertheless, this is a memorable book."

Lucinda Rosenfeld on "Wonderkid" by Wesley Stace:

The critique: "The novel would have been just as funny and far sharper at two-thirds the length."

The Reviewend: "Still, the Wonderkids' increasingly unhinged antics and eventual if predictable flameout ... are entertaining."

But it feels ungenerous to point out these patterns in a week when the Book Review provided us the insane, off-the-rail delight of director Peter Bogdanovich writing on a new biography of John Wayne by Scott Eyman, a shining example of how to review a book without engaging with it at all. (So: A page and a half essay lionizing an icon of masculinity but a terrible actor in an issue with cover art asking "Would you like this drawing more if a man made it?" Yes!)

Here are some of my favorite lines:

"The first time I met John Wayne..."

"Eyman begins his biography with an exciting prologue..."

"The book that follows the arresting prologue..."

"Among the most interesting things I learned from this book are how well Wayne expressed himself in prose..."

"As part of his research, Eyman interviewed me..."

The beauty of this "review" is that it's not at all clear from the way Bogdanovich expresses himself in prose that he ventured beyond the "exciting" and "arresting" prologue, other than to look for his own name in the index. It's deep into the first column that we get the first mention of the book ostensibly under discussion. The last 650 words or so don't mention the book at all. Beyond such insights as "extremely readable" and an "insider's journey" that "repeatedly rings true," Bogdanovich has plenty to say about Wayne but nothing else about the biography.

How would the New York Times Book Review end this piece? How about: Still, the beauty of a review this personal and breezy is how much of the book and John Wayne's iconic life it leaves for readers to discover on their own.

Shares