One evening when I was 8, in the candlelit kitchen of our apartment in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, I sat at the table while my mother stirred a large glass of Kahlua and milk. In the background, Bruce Springsteen sang of gritty streets and the sinister seduction of cocaine. Whenever Springsteen was on the turntable, the mood of our apartment turned morose, and I often felt weighed down by his music as if smothered in heavy blankets.

“I want to talk to you,” my mother said, looking up from her drink as she slid me a glass of chocolate milk. “About drugs.”

I nodded, and she went on. “I’ve done drugs,” she said. My eyes widened as she confirmed what I long suspected but didn’t want to believe. “And now I am done. No more drugs.”

At this time, a one-on-one with my mother was so rare as to be nearly extinct. My stepfather had recently left her, after a fight in which she charged at him with a butcher knife and slit open his palms as he struggled against her. He moved into his own apartment a couple of blocks away, but after a few months, he skipped town altogether and disappeared. The six months after he left and before we moved in with my grandparents were perhaps the loneliest and scariest of my life.

Mornings were unpredictable. They wavered between my mother refusing to get out of bed in the morning — time when I dressed and walked myself to school after tending to my toddler brother — and waking me up with slaps and violent shaking, due to her desperate dope sickness. She once yanked me out of bed so hard by my legs that I slammed down to the floor with a force that knocked the air out of my chest. I would then follow her into the kitchen while she banged the kitchen cabinets.

“I suppose you want breakfast, you little cocksucker,” she’d snap, while I stood still, my hands balled into tiny fists by my sides. At 8, I had no idea what a cocksucker was. I thought it was a reference to roosters.

So I’d give a stiff little nod, and in response she’d grab a plastic bowl from a shelf and hurl it in my general direction. After ducking out of its way, I’d pick up the bowl from the floor and proceed to the refrigerator for milk. My silence enraged her more (though then again, so did my words or tears, so I opted for silence in the hopes of being as inconspicuous as possible). Often, she’d grab me by my hair or neck, pulling me back toward her as I walked past.

“When I was your age, I could scramble eggs, but you can only pour yourself cereal. You’re useless,” she said as she let go of me.

Another of my failures was an inability to properly braid my Lady Godiva-length hair, which my mother would gripe about as she attacked my scalp with the plastic teeth of her comb. On the occasions when I squirmed too much or she was confronted with an especially stubborn knot, she would drag me across the peeling particle-board floor by my mane while she wildly waved a pair of scissors in the other hand, threatening to take away the only part of me I knew to be pretty. When she tired of the burden of my weight, she’d let me go and order me to braid my hair or she’d get rid of it for good. I’d stand there sobbing, my fingers shakily trying to thread three thick strands together while her scissors pointed tauntingly at my head. Eventually she’d give up on the threat and settle for a swift kick to my midsection or some more expletives whose meaning I didn’t know, but whose tone I couldn’t help but understand.

After school, my mother often went away for hours at a time, leaving me to babysit my brother and fix myself more cereal or a bologna and mayonnaise sandwich for dinner. When she returned, she banished Matthew and me to the bedroom or disappeared into the bathroom. Later on, I’d find her slumped in our lounging chair or sprawled out on the rollout couch, her legs and arms brandishing marks that looked like the vampire bites I had seen in the horror movies I was much too young to watch but which she’d allow anyway. My mother’s state veered dramatically between catatonic and so cranked up that, Catholic schoolgirl that I was, I suspected demonic possession. I kept half-expecting her head to start wheeling around on her shoulders like Linda Blair’s in “The Exorcist.”

When she came clean to me that night about her drug abuse, she didn’t apologize or show any sorrow over her vicious mood swings, of which I was the sole witness and scapegoat. Instead, she disavowed the junkie she was as though it were a separate spirit that had taken her over and that she had chased out solely through the brute strength of her own newly discovered willpower. After acknowledging her addiction and redemption in the same breath, she went on to offer a laundry list of reasons why I should never do drugs, which included macabre anecdotes, most of which I would learn much later in my life were merely urban legends.

My mother’s favorite story — the one she repeated more than once that night with a morbid energy that held me captive — was about a woman who spent Thanksgiving in the grip of an angel dust-and-heroin hallucination, and beheaded and stuffed her own newborn, mistaking the crib for her refrigerator and the baby for the frozen turkey. It wasn’t until the evening’s meal when she presented the decapitated body of the infant to her family that she realized the gravity of her error.

I asked my mother the obvious question of whether she had ever mixed PCP and heroin, to which she responded with an eager “yes!”

I paused, considering my sleeping brother in the next room.

“Have you ever done it in the apartment while we were here?” I asked, to which she — with a much more serious countenance — only nodded.

My mother went on to let me know that she had “done it all” — PCP, LSD, cocaine, crack, heroin and an assortment of pills, both “uppers and downers” and often mixed up together in an assortment of self-administered cocktails of her own creation. However, heroin was by far her favorite, or had been her favorite: the great love of her life.

Having finished her diatribe, my mother slowly took the stirrer out of her drink and licked it before pointing it at me with the same menacing gesture she had with her scissors.

“Don’t you ever do drugs, Laura,” she said. “Don’t you dare.”

* * *

Once a week two police officers graced my third grade classroom to inform us of the evils of drugs as part of the Drug Abuse Resistance Education, or D.A.R.E., program.

We viewed short films featuring hulking, tattooed black men pushing crack pipes into the hands of young, impressionable white children. We listened to gory stories of desperation and overdose. I raised my hand during one of these sessions and told the turkey story. My classmates were rapt. I asked the policemen if they had ever heard of this event. No, they said, but it didn’t surprise them. This could surely happen with someone on drugs.

I thought of my mother, home alone with my brother. I stayed silent for the rest of the day, my eyes constantly checking the clock, which was placed only a few feet above a plaque engraved with the Ten Commandments. After each interval of checking the time, my eyes would settle on the fifth one: Honor thy mother and father. I couldn’t ask the nun if this applied to parents who were addicts, because my mother told me I was not allowed to out what she was to anyone.

“They’ll take you away,” she warned. “You’ll never see your brother or grandmother again.”

That day after I told the turkey story, I ran straight home after school.

I found my mother dozing with the radio softly humming a Springsteen record and her right forearm freshly marked. Despite the bravado of her earlier declaration to give up drugs, she had only managed to stay clean for a few days. After checking her pulse (as she had recently trained me to do), I went to the kitchen where I removed all the knives from the drawers, as well as the one pair of scissors. I then brought them out to the alleyway of our building and tossed them into the dumpster.

When I returned, I fed my brother and myself some cheese and crackers for dinner. After that, I locked our bedroom door from the inside and pushed as many objects as my small body could muster in front of the door as a barricade against all the real and imagined horrors that existed on the other side. I switched on the small television and settled in for a late night of sitcom-watching, pretending the fictional families portrayed on the screen were my reality.

I didn’t dare leave the room for the rest of the night.

Many years later, I still shudder at the sight of sharp knives, as hyper-aware as I’ve become to how susceptible skin is to pointed objects.

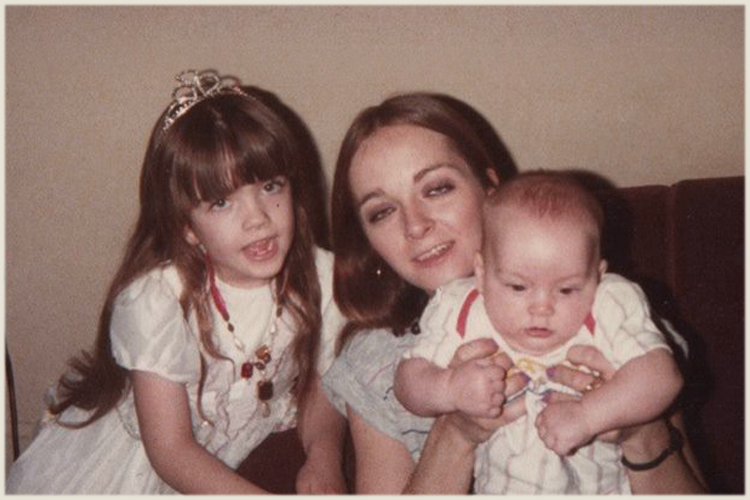

Whenever a celebrity overdoses, there is a surge of articles and essays from recovering addicts. However, we hardly ever hear from their children. I never did drugs, while my mother was never capable of becoming fully clean. My brother only ever knew my mother as an addict, which probably had something to do with him eventually becoming an addict as well. Being older, I had known her back when she was a working professional, an executive assistant to the vice president of CBS headquarters. I was the one who watched as our mother morphed from a smart but shy and soft-spoken woman to a depressed and crazed addict prone to violence and abusive behavior. She died at 52.

As an adult, I have never felt entirely entitled to my history. It does not make for appropriate dinner table banter, so I either evaded or outright lied when questions about my family came up (and they always do). I got away with it, because I was educated and articulate and people tend to believe what they see on the surface as the whole story. I didn’t fit the stereotype. But I felt rejected and even invisible as a huge swath of my past remained in the closet, mostly for the sake of not making others uncomfortable. I was angry that I felt forced to lie about my mother, who for better and for worse, had a great deal to do with shaping the person I became.

By lying about who she was, I was lying about who I was. So, I started telling the truth.