Even huge success in the literary world, it turns out, won’t help you sleep at night.

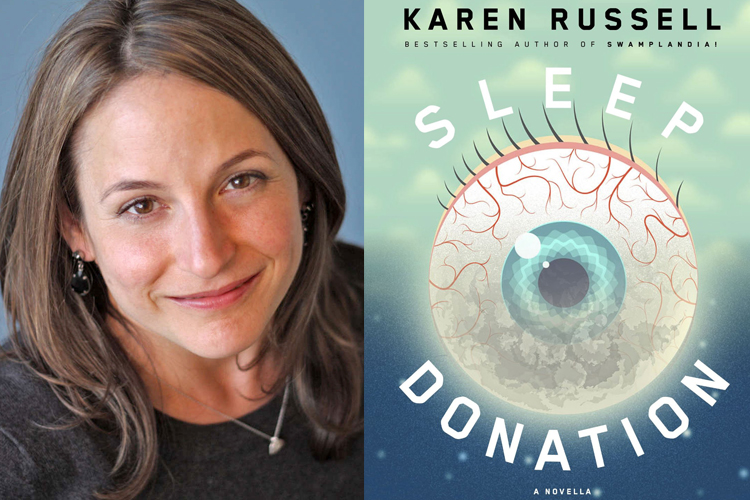

Karen Russell, the MacArthur “genius grant” recipient and Pulitzer nominee, has just released a novella, “Sleep Donation,” via web platform the Atavist. It’s set in a dystopian world in which crippling insomnia can only be ameliorated by the extraction and implantation of healthy sleep, most especially that of infants. The story expands outward from a sci-fi-tinged premise to depict people in the sort of crisis — mourning, confused, pushing against boundaries of propriety — that could happen in our nominally healthier real world.

Russell, herself, spoke to Salon in the midst of an interview blitz that had left her yet more tired than usual, but said that small-scale sleep deprivation is nothing new to her. Nor is the setting of human drama against the surrealistic or the strange: Russell’s first novel, “Swamplandia!,” puts a very real young teenage girl on a quest through a fever-dream, haunted Everglades. The title story of the recent collection “Vampires in the Lemon Grove” is not strictly figurative — the story’s really about vampires who slake their addiction to blood with citric acid.

Since the publication of her debut collection “St. Lucy’s Home for Wayward Girls” in 2007, Russell’s been among the foremost chroniclers of American preoccupations and peccadilloes. If George Saunders’ chosen device to get at the nature of modern life is the soulless corporation that tries to crush the spirit of its employees, Russell’s is the event explicable only by magic that gets at the very real nature of people.

“Sleep Donation” is no exception — indeed, it’s a worthy addition to the Russell bibliography, though purists may argue about the degree to which it, published at its natural length of 110 pages online, is or is not a “book.” Exercising her gift for metaphor, Russell told Salon: “One of the things this offered me that was completely new was the opportunity to build out the story so it could have a placental existence in cyberspace.” As for the degree to which she feels nervous about her reputation as the sort of wunderkind who haunts “[Number] Under [Number]” lists and is fearsomely accomplished for her age, Russell cracked that she didn’t feel young at all and was stymied by anti-aging products at the pharmacy. A surrealist outlook can take many forms.

“There’s a crush of sensation in your day-to-day life, so here’s a parallel universe where you can feel again,” Russell told Salon of her favorite works of fiction. “Sleep Donation” — and its challenging presence on the illuminated screen where its readers click through Twitter and email all day long — does the same.

Hi!

Hi, I’m sorry, doing these interviews today, I ran out of go juice. One of the questions that comes up in a situation like this is, “Do you have trouble sleeping?” And insomnia has a confirmation bias — the more you talk about it the worse it becomes. I worry I’m no longer making sense!

So, looking at it as objectively as you can, do you have insomnia?

In a really funny way — “funny” is my stand-in modifier for a thousand other modifiers — I’ve always had difficulty or strangeness with sleeping. I never sleep all the way through the night. I couldn’t tell you the last time I went to bed at midnight and woke up at 8 — but that’s the case for many people. I never had the kid of truly monstrous insomnia that I write about in this novella. It put things in perspective for me.

One of the things I lost writing this novella is the license to complain about my own sleep deprivation. I was writing about cases that are heartbreaking and mysterious. But I do know that the problems you come at hard during the day show up in your dreams — that happens to me with my drafts, and with my students’ drafts.

They must be doing something right, then.

Right! They’ve successfully translated their concerns into my body with language. It’s a strange feeling to encounter your preoccupations in “Alice in Wonderland” proportions when you’re dreaming.

Your work tends to take place in surrealistic or dystopian settings but to be about more than the details of the setting. How do you strike that balance and keep the extravagant details from taking over the whole?

I guess it’s just about making new observations in those dreamscapes, shifting the balance. You ask yourself what’s supernatural in this universe, and what’s ordinary and banal. When I wrote that first collection, I was so naive. Someone said to me, “You’re a fabulist,” and I said, “Thank you, I think you’re fabulous too!” I wasn’t so conscious of being … Well, what I knew deeply in a realm beyond thought were the books I loved: Calvino, García Márquez, Kafka, Atwood, Stephen King … These folks seemed to be in a twilight space, a crepuscular space that didn’t read as unrealistic but was exaggerated in scale so you could see them more clearly, a funhouse mirror where things can rise to salience. There’s a crush of sensation in your day-to-day life, so here’s a parallel universe where you can feel again. I wanted to make worlds that could do that for readers.

I’ve shifted away from talking about magic and realism as though it’s a binary, but I used to tell classes about the Kansas-Oz binary. The world you’re working on has elements of the real world, so what’s the ratio of bedrock, lumber, brick-and-mortar details that make a world feel real and give the extraordinary elements the oxygen they need?

Your readers need to be able to get into the world in order to understand the larger points you’re making.

Well, there’s the fishwrap-to-the-face technique: “As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into a gigantic insect.” That’s the ante for the reader. Can you go along with this? If you can accept these terms, then we can be friends! Let’s proceed to the next paragraph! Italo Calvino — I love his story “The Dinosaurs.” It’s told from the point-of-view of a bombastic, drunken Italian uncle of a dinosaur who happened to survived the death of his species. That sort of matter-of-fact confidence dismantles your doubts automatically. Writers I really admire are skillful at making these spaces their own universe. I don’t think there needs to be one-to-one correlations between the world of the dinosaurs and Miami, Florida, or Iowa City, Iowa. It’s not a perfect overlay, but there are resonances — a wonderfully uncanny space that is an alien space, but things feel familiar. That vertigo, that productive defamiliarization, is one of my favorite sensations as a reader.

You’re seen as an author, I think, who’s been remarkably productive and successful for your young age…

I like that I still get to be young! I don’t know anymore! I was speaking to my brother the other day and he thought I was 29 — I told him “No, I’m marching forward on the calendar!” (Russell is 32.) I’m young? Not in my family! They say, “Hey, crows’ feet, what’s up!” There are these embarrassing age-defined products. You’re a young man, aging for you will just mean that you’ll appear to have acquired resources. On the other side, there are these products that seem named to humiliate us and were devised by a cruel warlord. “Age Regenerist”… Oil of Olay… this black logo, it looks like you’ve contracted with some wizard at the end of the world to do something evil but necessary to your face.

Do or did you feel anxiety over success coming relatively early?

I think I feel profoundly lucky — I was raised to be suspicious of good fortune, so I almost can’t fathom it. There is a degree to which I know some of it was just blind luck and serendipity. A lot of it has been the support of people I really respect. I will not forget that — the people who made me feel like a real writer. I had a story come out in the journal Conjunctions, and the editor Bradford Morrow had me talk to his class at Bard when I was 23 or 24, at an age where that intervention felt so necessary. A lot of writers are in a Zen state, and they don’t need validation, but it’s always been so heartening for me. I don’t think I’ve really processed a lot of it yet. I’ve got a lot of emotional back taxes to pay.

Did getting an MFA at Columbia help provide validation — and would you recommend it to young writers?

It really is case-by-case. I’m in a funny position now where I find myself, when I teach undergrads, recommending they take some time before they apply to MFAs. That was not what I did. I felt an urgency that in retrospect feels totally lunatic to me. I have nothing to compare it to except being in love. This is all that I want to do. I wasn’t even thinking about — financially, I made some dubious moves. It turns out it’s really easy to get loans — somehow that’s, in retrospect, like walking across a construction beam. I don’t understand how I made it across. It feels like supreme luckiness. But to have the time and be with self-selecting wizards of words who think it’s valuable to spend a lot of your waking life transcribing dreams and imaginings, listening to the music of senses, that’s valuable. It’s a pretty lonely existence.

Your putting this work online feels like something of a statement. Do you feel like it was the right call? Do you feel as though the traditional model, whereby an excerpt would have ended up in a journal and the whole thing as part of a collection, isn’t always working?

I felt like there were some serendipitous forces at work, working on this sketch about a nightmare that goes viral, an escalating mental virus — it was so informed by my own experience of what it’s like to be alive right now, with these technologies that have tremendous amplifying potential. From the moment I met [Atavist co-founder] Frances Coady, this seemed like the perfect form for this content, and I loved writing it for this format. To do a 110-page story … I don’t know any magazines where it’d find this form. The transmission felt so right for this project. With writers like Chris Adrian and Hari Kunzru, they’ve invested new resources into their stories, too. We only have a finite set of stories and preoccupations, and they make it new.

I have loved publishing stories with magazines like Tin House and Zoetrope and I hope to do it in the future. But this felt like the right way to do this story. It was so exciting to be in collaboration with other minds, because writing can be a lonely endeavor. The editorial collaboration is what I’ve always loved. As a non-athlete it’s as close as I’ll get to sports, or being in a band.

The pleasure of writing, not all of my pleasure but a lot of it, comes from building a world, ordering a cosmos with a setting and humans and a landscape. Getting to do that work with artists with skills that I just don’t possess was amazing; [the designer] Chip Kidd did a translation of the tone of the book. One of the things this offered me that was completely new was the opportunity to build out the story so it could have a placental existence in cyberspace. Imagining how the content of this novella could gesture outward onto the Internet and the act of downloading the thing … that’s what felt exciting about that opportunity and connected it to the story of how dreams travel.

The sense of a dream “going viral” feels very Internet-age.

The fluidity of that, the sense of implication, anonymity and the sense of interconnectivity. So much of the story is about how porous things have become between healthy bodies and sick bodies and what we owe to one another. What we owe to one another — freedom and connection — and how we can give that without violating boundaries. It felt intuitively right that this would be the site for this. I’m not a businesswoman so I don’t know how the [publishing] model will change. I felt like magazines fledged me in a way, so I feel huge gratitude to them, and I don’t think they’re going anywhere. We’re in the Wild West with lots of chaos and lots of opportunity. But I have faith that writers will continue to make it new.