The question of whether we once again find ourselves in an age of narcissism has recently captured public attention, with a variety of pundits, psychologists, and self-styled Internet-based experts weighing in on both sides. Those answering in the affirmative argue that narcissism is dangerously on the increase and visible everywhere: in rampant consumerism and failed marriages, on Facebook and Twitter, in the executive suite and the halls of government. To them, narcissism again explains everything that is wrong with American culture. The situation is far more dire now than it was in the 1970s. The critics see the civic bonds that Lasch believed were fraying threatened anew by an epidemic of individualistic, self-seeking, and self-promoting behaviors especially evident among the young, the most narcissistic generation in history. In this view, the so-called “Generation Me” suffers from an excess of vanity, entitlement, and ill-gotten self-esteem. The evidence is there—the claim is that 10 percent of twenty-somethings and 25 percent of college students exhibit narcissistic pathology—and the prognosis is not good.

The case for the precipitous rise in narcissism among Americans today rests largely on surveys—especially the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI)—administered to college students from 1980 to the present, and is made most vociferously by the psychologists Jean M. Twenge and W. Keith Campbell, who compiled and interpreted results from thousands of tested students in their widely cited 2009 book, The Narcissism Epidemic: Living in the Age of Entitlement.

Research psychologists have used the NPI since its development in 1979 to measure and predict narcissistic behavior. The test, which can be found on the Internet, asks subjects to choose between two responses to forty questions. Among them are questions measuring grandiosity, entitlement, and exploitativeness, for example, “I insist upon getting the respect that is due me” versus “I usually get the respect that I deserve”; “I find it easy to manipulate people” versus “I don’t like it when I find myself manipulating people”; and “I will never be satisfied until I get all that I deserve” versus “I take my satisfactions as they come.” These questions measure dimensions of narcissism that both researchers and clinicians consider pathological, and there is agreement that they do this well.

Psychologists critical of the NPI argue, however, that a number of the test’s questions measure not pathological narcissism, as its proponents claim, but the positive traits of high self-esteem, psychological health, assertiveness, and confidence. Among these questions are “I think I am a special person” versus “I am no better or worse than most people”; “I see myself as a good leader” versus “I am not sure if I would make a good leader”; and “I am assertive” versus “I wish I were more assertive.” The first of each of these paired responses increases a subject’s score on the NPI, and in the aggregate provide evidence for the ubiquity of narcissism. From the 1950s to the late 1980s, the percentage of teenagers agreeing with the statement that appeared on another test, “I am an important person,” jumped from 12 to 80—an increase larger than any seen on the NPI. Twenge and Campbell consider this finding an especially significant sign of the increase in narcissism. “We think feeling good about yourself is very, very important,” Twenge told a journalist in 2008. “That never used to be the case back in the ’50s and ’60s.”

Some psychologists—Campbell among them—have argued, however, that high scores on the NPI may in fact be indicative of healthy narcissism. The test as it is used now cannot distinguish (nor was it meant to) between pathological narcissism that has negative implications for others and healthy narcissism that is, many clinicians would argue, benign or even a sign of mental health and the foundation for robustly engaging with others and the social environment.

Campbell acknowledges that narcissists, with their high self-esteem, may in fact be happier, more satisfied, and more successful than their nonnarcissistic peers. He admits that research shows that the social psychologists’ narcissists are happier than the clinicians’, who conform more to Lasch’s fragile, empty, and depressed modal type. It is possible, Campbell writes, that the narcissists who end up in psychiatrists’ offices and on analysts’ couches are failed narcissists, those “not doing their ‘job’ correctly”—the job consisting in “achieving and winning.” He concludes that “narcissism may be a functional and healthy strategy for dealing with the modern world,” invoking Freud’s 1931 sketch of the narcissist as a larger-than-life personality striding confidently across the world’s stage.

It may be, as one psychologist told a reporter, that “eighty percent of people think they’re better than average,” but, he added, it was also the case that “psychologically healthy people generally twist the world to their advantage just a little bit”—echoing Freud’s observation that “confidence in success . . . not seldom brings actual success along with it.” And, to be sure, self-esteem can sometimes appear frustratingly reflexive, as in the statement of one young woman that “I am always confident in myself because it will lower my self-esteem if I’m not.” Easily held up to mockery, self-esteem and “unflappable self-confidence” could yet have real effects. Consider the case of a Harvard student recently profiled in the Boston Globe, raised in poverty by an overworked single mother, who credited her high school teacher’s lesson that students should “realize the genius in their inner self” with empowering her to follow her dream of becoming a skilled debater. In the same article, a twenty-four-year-old from an equally deprived Boston background, who started his own company, said he was grateful that his confidence kept him “a little ignorant, maybe even a little arrogant,” because otherwise he would never have done anything. It is possible that rising scores on the NPI reflect this kind of self-esteem. As two psychologists argue, higher overall scores may indicate not an increase “in egotism and self-centeredness” or “narcissism at all” among the young but may instead reflect “positive, rather than negative societal change.” They may also reflect the fact that the popular language of self-esteem is relatively new; the first generation of children raised on it were born in the 1980s and 1990s.

Some argue that there is nothing new in the current condemnations of the fecklessness of the young—that, in the words of one psychologist, “every generation is the ‘Me’ generation.” The notion that overconfident youth will have its deserved comeuppance is hardly novel. In the 1960s, the older generation poked fun at the identity crises of the young, asking whether they were uniquely miserable in their angst—was their collective crisis not just the personal crisis of the past in an updated form? In the 1970s, as we have seen, bemoaning the narcissism of the young—their “fatuous self-absorption”—was a minor industry; from the perspective of 2008, one self-described Boomer wrote that he found “the notion that today’s students are even in the running for narcissistic self-absorption with my own cohort absolutely hilarious.” The essayist Logan Pearsall Smith has quipped that “the denunciation of the young is a necessary part of the hygiene of elderly people, and greatly assists in the circulation of their blood,” and any number of assessments of youth today as lazy, irresponsible, overconfident, and entitled supports his contention. As Time magazine has pointed out, the young were denounced by their teachers as pleasure-seeking and “so selfish” in 1911 and there was no shortage of condemnations of jazz-crazed flappers in the 1920s. Is posting photos on Facebook any more obnoxious “than 1960s couples’ trapping friends in their houses to watch their terrible vacation slide shows?”

Psychologists’ disagreements are not confined to the professional journals but, rather, featured in the popular media. “New Study Finds ‘Most Narcissistic Generation’ on Campuses, Watching YouTube” raises alarms; “Students Not So Self-Obsessed After All” reassures. The New York Times regularly assesses the state of the narcissism question, with articles featuring some psychologists warning of cultural disaster and others maintaining “that the dire warnings of a rise in selfishness were baseless.” Separate from this is a lively, complex, and ongoing conversation about narcissism focused less on the issue of its prevalence than on dealing with its alluring dangers. Books and websites offer nuanced, sophisticated portrayals of narcissistic pathology as well as advice on identifying, dealing with, recovering from, and, most useful of all, altogether avoiding narcissists, whether at work or in intimate relations. Freeing Yourself from the Narcissist in Your Life; Narcissistic Lovers: How to Cope, Recover and Move On; Children of the Self-Absorbed: A Grown-Up’s Guide to Getting over Narcissistic Parents: the list is long, the operative concepts variants of how to manage, recover from, and otherwise deal with, or distance yourself from, what one title terms “infuriating, mean, critical people.” Much of this advice channels a Kernbergian vision, characterizing the narcissist as an interpersonally enticing but dangerous figure who snares unwitting victims in his charismatic net while callously draining them dry. Unlike the narcissism of the research psychologist’s NPI, this popular narcissism can be every bit as paradoxical as the analyst’s. The Everything Guide to Narcissistic Personality Disorder, for example, offers a complex version of narcissism in nontechnical language. And, ordinary people wounded by narcissists offer wrenching testimony on the web to the confusing allure of the narcissist, as well as to the devastation that often follows in its wake, drawing on the writings of professionals but also on readings in the press and popular books.

In the leadership literature focused on the charismatic narcissist, which employs an analytic understanding of narcissism, malignant and healthy narcissism are given equal weight; the leader’s strengths are also her vulnerabilities. In the popular discussion, by contrast, the negative findings and alarming numbers offered by research psychologists tend to dominate. Consider self-esteem, which research psychologists and psychoanalysts conceptualize differently. To many research psychologists, high self-esteem is symptomatic of narcissism, and healthy narcissism seems a “vague and somewhat meaningless way of describing ‘all human efforts.’” For analysts, by contrast, it is more often low self-esteem that is problematic (as in, overly inflated self-esteem is not what it appears to be, often interpreted as a narcissistic defense against actual low-esteem), and healthy narcissism is seen as a clinically useful concept. Self-esteem to analysts is fungible, and since the 1970s they have envisioned people regulating their self-esteem in the interest of maintaining positive feelings about themselves. There is nothing new about this process, often called narcissistic. Talk of self-esteem is not cause for alarm.

Gendered Vanity

Just how limited the popular conversation about narcissism is can be glimpsed in the current conversation about female vanity, which barely registers analytically but figures centrally in popular condemnations of modern women as narcissistic: overly obsessed with outward appearances, entitled and self-absorbed, holding—as one woman admitting to guilt of the same put it—“an inflated sense of our own fabulousness.” Condemnations of fashion and the female vanity on which it purportedly depends are everywhere, and it is easy to cast women as hapless victims of media-fueled bodily narcissism—“beautifully painted and clothed with an empty mind” is how one woman recently surveyed characterized “how people are becoming.”

Vanity, aesthetic appreciation, envy, self-possession, beauty, exhibitionism: this is where talk of female narcissism started and where, in much of popular discourse, we are today. The dictum that narcissism—and the self-admiration symptomatic of it—is more pronounced in women than in men went largely uncontested in the theorizing of Freud and his colleagues. And the purportedly greater female disposition to exhibitionistic display—especially evident in the project of self-making around clothing—is a staple of both the historical and contemporary discussions. But the continuities these similarities suggest are illusory. The earlier discussion was as much concerned with the pleasures as with the pathologies of narcissism. It envisioned a self reveling in sensuous experience of the world, and examined the ways individuals brought the objects among which they lived into the “Me.” In place of the richness of the early analysts’ explorations of vanity and expressiveness, we now have censoriousness and disdain for women’s desires.

The psychoanalyst J. C. Flügel argued in 1930 that clothing engendered envy, jealousy, petty triumph, spitefulness, struggle, and painful contests for superiority among women. Men were almost completely indifferent to female attire, Flügel argued. “Women dress much more to please their own vanity and to compete with other women” than to elicit male admiration, he observed, wistfully imagining women tempering their self-satisfied narcissism and turning their attention to men—other than their dressmakers. Flügel worried that women’s capacity for heterosexual object relations was diminished by the narcissistic satisfactions offered by wearing, displaying, and competing with one another through the medium of their attire. Some recent psychoanalytic commentators in effect assent to Flugel’s observation while adding a positive dimension to it, exploring the many ways in which the circulation of clothing among women—shopping, dressing, admiring, evaluating—constitutes a concretely apprehensible and “highly ambivalent” form of object relations expressive of the emotions rooted in the earliest relationship to the mother—“love, hate and envy.” Clothing shoulders a heavy expressive load in women’s lives from this perspective, serving as “a way of displaying the body, as an indicator of economic power, as an incitement to envy, and as a sexual enticement.”

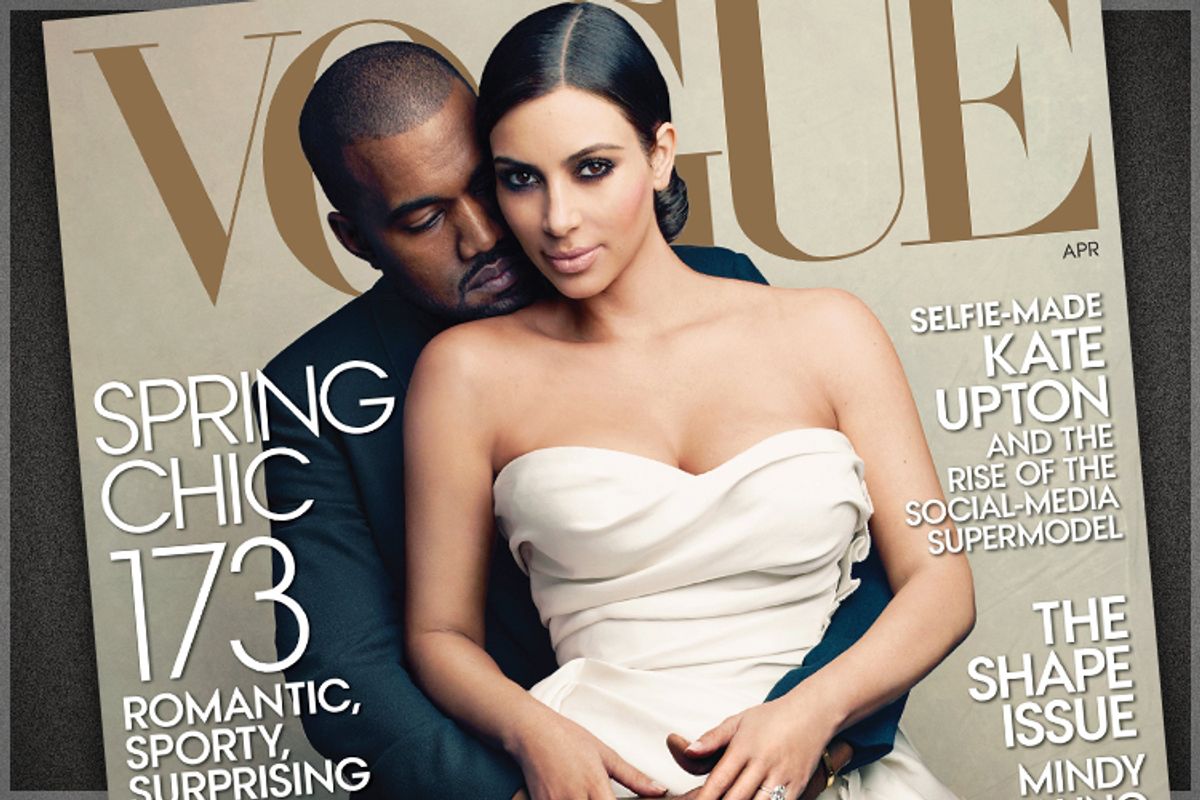

“For all of Generation Me’s lifetime, clothes have been a medium of self-expression,” writes Twenge in Generation Me, highlighting the individuality that now is expressed through dress in contrast to the rules and conformity of the past. Raised on a “free to be you and me” ethos that advocates wearing what one wants to, “not just what other folks say,” today’s young are interested in things “that satisfy their personal wants and help them express themselves as individuals.” People increasingly dress for themselves, Twenge argues, for comfort rather than to elicit the approval of others. Narcissists today are inordinately interested in “new fads and fashion,” and like to both display and look at their bodies. Vain and self-centered, they spend a lot of time focused on looking good.

All of this here presented as new and alarming would have been familiar to Louis Flaccus, our early-twentieth-century psychologist of clothing, who more than a century ago surveyed students about clothing’s relation to the self. Flaccus and his subjects celebrated the material pleasures of clothing. He expounded on the ways certain sorts of clothing were allied with a “slackening of self-restraint” and recognized “the sensual delight in one’s body as body” as an exemplary expression of the “joy of living,” none of which he associated with narcissism. Given the NPI’s dichotomous choice between “my body is nothing special” and “I like to look at my body,” the subject wishing to keep her score low will chose “nothing special.” Not for her the exuberance and exhilaration of Flaccus’s subjects, “glad to be alive” in donning the loose clothes appropriate for an outing, glorying in the “‘I don’t care’ feeling” such garments encouraged and delighting in the “delicious feeling about tripping up one’s usual sober self.” Among Flaccus’s subjects were avid shoppers, but there is none of the reproving disdain of today’s commentators on narcissism in his work, which is awash in self-feeling, pleasure, sensation, illusion, and the delights of appropriation, of clothes “gradually becoming part of ourselves.”

The contemporary Laschian perspective that casts all consumption as pathological is of little use in distinguishing between shopping that is experienced as pleasurable and shopping that is experienced as a compulsion, even an addiction, that must be engaged in at the price of unbearable psychic distress. As exemplary of the latter, consider, for example, the woman cited in a 2000 article who likened “extended clothes-shopping” to an injection and another who described “how she got the shakes if she was deprived of the opportunity of shopping because she was on holiday in a remote location.” Surely, a robustly conceptualized theory of consumption would allow that the meanings shopping has for these women, who speak of it in the idiom of substance abuse, differ from those it had for Flaccus’s enchanted subjects or Twenge’s, female and male alike, instead of characterizing them all as narcissistic in their materialism. Since the mid-1980s, a body of literature by psychologists, psychiatrists, and psychoanalysts, as well as sociologists, on compulsive shopping has explored these meanings, offering testimony to their complexity, as well as, in some cases, to how rudimentary understanding of the phenomenon can appear. This literature casts compulsive shopping as a largely female disorder that, variously, offers “escape from psychic pain,” represents a “flight from feminine identification,” is a form of self-harm akin to delicate self-cutting, and—here we are back in the company of Freud and his colleagues—is at root “a deferred reaction to anxiety over castration, the first cognizance of the lack of a penis.” Market researchers and the social scientists who study them are a step ahead of disapproving social critics, having devised elaborate and largely value-free taxonomies to classify shoppers and their habits: apathetic or recreational, indifferent or gratified, browsers or buyers. They have shown that women tend to cast shopping for clothing—including window-shopping without purchasing—as a legitimate indulgence and a harmless means to pursue pleasure, much as did the early theoreticians of dress. Recall that in that early discussion, men as well as women indulged in the sensuous delights of clothing. Since then, however, men have managed to define shopping as work not play, enabling them to satisfy their impulses to consume—cars, appurtenances of household and yard, electronic gadgets—even as they disavow them by associating them with women and feminine desire.

Flügel took comfort in observing that women did not on the whole laugh at men for their prickliness about clothing, though he had to admit this was likely due more to indifference than to any kindly regard they might have had for men. Now, however, as men emulate the clothes and body consciousness that were once solely women’s province, the laughter prompted by the narcissistic baby boomer male’s “ungraceful descent into middle age” is audible. Expensive antiaging potions disguised as shaving cream; plastic surgery promoted not as cosmetic but as an “investment that pays a pretty good dividend”; diet advice parading as tips for eating out—“it’s almost impossible to tell whether you’re reading a copy of Men’s Health or Mademoiselle,” writes a female journalist, gleefully observing of the men subjected to the tyranny of impossible beauty ideals that has long been women’s lot that “at least the burden of vanity and self-loathing will be shared by all.” Writing of the vogue for uncomfortably tight, low-rise jeans among his peers, a male journalist contends that “American men have come to vanity late and practice it with the zeal of the newly converted.” He sees men co-opting a peculiarly female vanity—even, more concretely, their jeans, with men scouring women’s departments for suitably low cut varieties—and decrees, “we need to suffer to look good,” testifying to their narcissism in spending stupidly on “hair cuts and shirts rather than car stereos and television sets.” Flügel would not have been surprised at these men’s seeking out the “erotic, masochistic” feelings imparted by the too-tight pants that drew this journalist’s ire, and he might not have fully comprehended but surely would have approved of the “super-fucking macho” orientation—or, at the least, of the heterosexual side of the phenomenon—they signified, his concern always that men were insufficiently invested in their own attractiveness to women. Maybe men, a contemporary journalist muses, are finally copying women, now that women wield real power in the world.

We are told that today’s young narcissists—much like the Me-Decade narcissists of the social critics—have been coddled from birth and have grown into entitled, materialistic, shallow adults, obsessed with their appearances and addicted to shopping. What is to be done? The critics’ remedy, in the 1970s, was in part to reinstate a culture of remissive “shalt nots” and “shoulds” whose passing was lamented by Philip Rieff and Lasch. The “fixed wants” of times past—associated in Rieff’s history with obedience, limitations, renunciation, abstinence, and deprivation—were to be restored through a program of asceticism in those who had tasted the delights of impulse release. Writing in 1960, the adman Ernest Dichter suggested—in effect addressing social critics’ recuperative fantasy—that those who decried their own materialism on Sundays while living in a world of material plenty the rest of the week were guilty of a mild hypocrisy. “Agreed, we should drop our interest in worldly possessions,” he wrote. But how were we to actually renounce this “only too human desire?” Dichter’s charge that we “steadfastly refuse to accept ourselves the way we actually are” is as apt today as it was more than fifty years ago.

In "The Triumph of the Therapeutic," Rieff ruefully expressed his doubt that “Western men can be persuaded again to the Greek opinion that the secret of happiness is to have as few needs as possible,” voicing the narcissistic fantasy of the self without needs that animates the literature of lament. The position of self-sovereignty that Rieff and other critics ascribe to the nineteenth-century bourgeois is descriptive of an unrealizable fantasy of independence and autonomy that serves as foil to the modern’s purported neediness and enmeshment. This popular strain of commentary is nothing but the narcissism of the theorist, revealing his desire to inhabit a persona without needs and attachments. Such was Freud’s fantasy as well. In short, the culture of narcissism might in the end be more the province of the orthodox analyst and the ironic, detached, and contemptuous critic of modernity than of the self-absorbed adolescent, the shopaholic woman, and the aging Boomer still in search of his self.

Excerpted from "The Americanization of Narcissism" by Elizabeth Lunbeck. Copyright © 2014 by Elizabeth Lunbeck. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Shares