“You are so blessed!”

“You’re an angel!”

“Are you Catholic?”

“Are they all yours?”

“God bless you!”

These statements are just a sampling of what people say to my husband and me when they find out we have seven children.

We have a blended family — three biological children and four who came to us from Tennessee through an interstate adoption program. Strangers and casual acquaintances step into our circle to celebrate our “good deed” as if we’re doing something to please God. These well-intentioned people have no clue that we are hiding something very important from them: our identity as atheists.

Most people assume it was our faith that led us to adopt. But after hearing all sorts of mischaracterizations and faulty conclusions about who we are, it’s time for me to speak up. We’re not religious and we’re adoptive parents.

In fact, because I’m a happy Secular Humanist parent, I have chosen to advocate for adopting older children and working through the complexities of interstate adoption. My hope is that we can encourage other secular families to find and take in children of their own. For too long, adoption has been linked with religious groups — not always, but often. That needs to change.

I don’t mind discussing adoption or atheism. The two have a lot in common and, in fact, both subjects can learn a lot from each other. Neither needs to be a secret and I don’t want my kids to be ashamed of either label. However, those labels also don’t define our lives entirely; we are constantly evolving and growing and learning new ways to describe ourselves. (When you have seven kids, the definitions change frequently!) People celebrate adoption and many celebrate their own atheism, but the two worlds rarely intertwine. Both worlds are filled with rejection, intolerance and misunderstanding. There are angry atheists and there are angry adoptees. We are, however, on the happy end of both spectrums.

When I first discussed adoption with my husband, he assumed I wanted to travel to China to bring home a newly-born baby. It was hard for him to grasp that I wanted to adopt a child and not an infant. I wanted to provide a home for a child who had grown up without one, not mold a child from birth. There’s a stigma against adopting older children (above the age of eight) and, before I even met my children, I had many people tell me why it wouldn’t work.

Each of our kids has struggled with one issue or another regardless of whether they were adopted or not. All kids can be reckless, hurtful and rebellious, but that’s especially true if the adults in their lives have let them down. It’s upsetting that our adopted children’s biological parents couldn’t have raised these four amazing kids and we’re sad that, in order for our kids to be loved and cared for by us, they had to be separated from their biological parents. Our gain doesn’t make up for their loss. (In a unique twist we have re-established a connection between our kids and their biological parents. Having an open adoption after no contact for a few years is scary for some people, but it has been beneficial for all sides in our case.)

So why did we choose to adopt?

I should start by telling you that my husband never wanted to do it, though he has since become adoption’s biggest advocate. The process took years and, though our biological children were excited at first, the time lapse began to wear on them after a while (Will we ever meet our new brother or sister … ?). The romantic idea of adoption is that it happens quickly; the truth is that the length of time from start to finish can vary quite a bit. The average time foster children spend in care is 3.5 years.

My motivation to adopt is complex, though it might help to explain my own background. I was the product of an affair my mother had while she was married. She met my biological father in college and I learned very few details about him when I was younger. I was told he was Russian and Jewish, though he was actually Polish. I was told he was studying to be a physician, when he was actually a psychiatrist. I was told his name, which my mother remembered somewhat incorrectly. So the true story of my own conception was a mystery to both my legal father and biological father until I was an adult, when my mother finally revealed the truth to both of them. I suppose that story could have crippled me, but instead, I feel like I became more compassionate.

The search for my “real” self led me to read many books about adoption. To my surprise, I strongly identified with many of the experiences of adoptees. I, too, had a strong appetite for an “adoption story,” to be reunited with my biological father and seek out cultural, ancestral and medical information. Though most of the books spoke from a religious perspective, I was able to read around these spiritual findings since I had given up my faith by this time.

During our adoption search, we were approved by three different agencies: our local Department of Social Services (DSS), Lutheran Family Services and a private therapeutic foster care agency. Each agency served an important purpose during the many years we worked with each of them. For starters, we worked with our local Department of Social Services as respite foster care parents, meaning we gave regular foster parents support or a short break by taking care of their kids for an afternoon or a weekend or longer. During our time as respite parents, we were able to help children and families during times of crisis, without becoming official long-term foster parents. It was like we had adoption training wheels.

During our home-study process, when adoption agencies can assess whether we would make good adoptive parents, we were asked about our religious upbringing, the church we currently attended and how we would respect the foster child’s culture and potential decision to attend a church different from our own. We never volunteered our atheism, nor were we asked; the social worker did, however, assume that we attended church. I suppose she had no reason to think otherwise — parents always adopt because of their faith, right? At least, both private and state agencies always wanted to know that information. I understand the need for thoroughly vetting a prospective family, but it’s not like they ever asked us about our political affiliations …

We eventually decided the best option would be to avoid mentioning our lack of religious beliefs if at all possible. As a “waiting-to-adopt” family, our atheism was setting us up for a wide range of discrimination and intolerance. While many adoption agencies target all kinds of different parents these days — including single, older, interfaith, gay, lesbian, transgender and interracial ones — they still tend to ignore secular families. We’re just not on their radar. Since most agencies are funded and run by churches and religious foundations, it is assumed by many staffers, case workers and social workers that the religious faith of the adoptive family alone means they are worthy of parenting children. Most social workers who came to speak with us (as part of a background check) assumed we attended church. We were firm in telling them that we didn’t, but that we respected the children’s right to make that decision for themselves when the time was right. I worried that our atheism would raise some sort of red flag in these agencies, forever marking us as Unfit to Adopt.

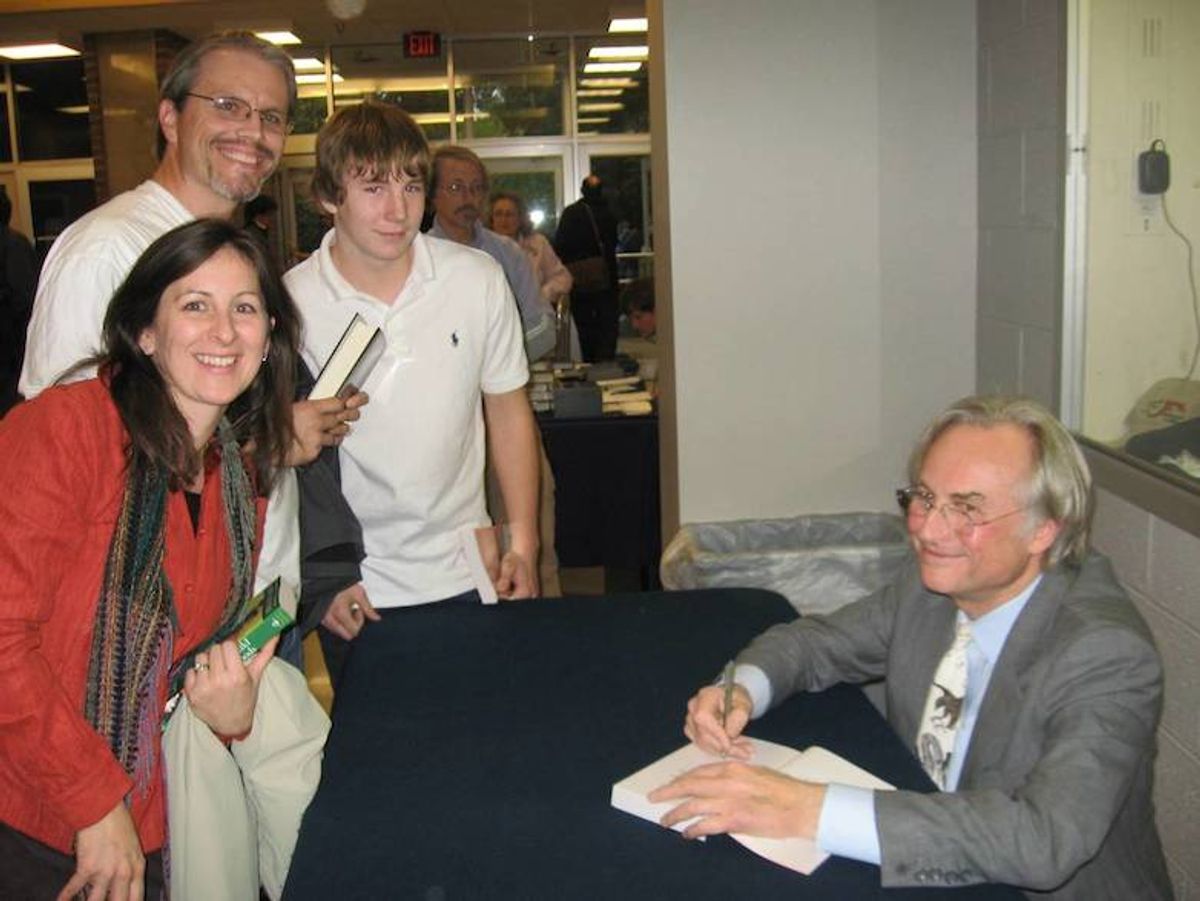

[The Gilmores meet Richard Dawkins]

Even during the mandatory monthly foster parent meetings, I quickly learned that there was a degree of favoritism and intolerance depending on one’s experience. As a new foster parent, I was eager to share what I was thinking, but I discovered the more religious you said you were, the more popular you became within the group and the more placements you received. I never felt I was able to declare my lack of religious belief to the foster care group because I feared I wouldn’t find any support. Meanwhile, other foster parents freely discussed their religious beliefs and even their disgust with a political party with no hesitation. I have seen the same attitudes in other foster care groups, too. I once declared that I didn’t attend church and that I wasn’t very religious, only to be subsequently invited to the foster parent’s church where her husband was pastor. I declined. After that, I was coldly rejected from the group and other future events. Declaring my difference made me an outcast and never benefitted my family. So I decided it would be better to accentuate my family’s values instead of a particular religious label so that we could steer clear from the religiosity that continues to support those who are believers.

That’s when we began inquiring about kids via AdoptUSKids.com. This website became my go-to resource for adopting children in the United States, specifically older children as opposed to infant adoption, and explained the whole process as well as the more complicated proceedings of an interstate adoption. It taught me that waiting families don’t have to adhere to someone else’s idea of “perfect” in order to adopt.

Because our DSS office didn’t participate in interstate adoptions at the time, we switched to an adoption agency that would provide us with a home study that was recognizable by other state agencies: Lutheran Family Services of Virginia.

By this time, we knew better and didn’t express our lack of religiosity to them, but we stated honestly that we did not attend church. We were approved as adoptive parents with LFS on the basis of our experience and recommendations from the state agency.

That’s when we stumbled upon a potential roadblock.

On Feb. 10, 2012, the Virginia Senate passed SB 349. Known as the “conscience clause” bill, it was described as targeting LGBT populations in Virginia, but it also declared differences in religion as a factor for adoption. That meant that agencies receiving millions of dollars in state funding could discriminate against families they believed did not fit into their doctrine. I felt our opportunity to adopt disappearing. Words could not express my frustration. I promised my family I would never surrender.

Thankfully, those worries never came to fruition. We soon received a call that we would become parents — to a group of four siblings from Tennessee. We became adoptive parents because we were qualified and we had the qualities that these children needed. We did it without any help from god and without the support from Lutheran Family Services of Virginia. And while we weren’t expecting that many children, we can no longer imagine our lives without each one of them.

Having gone through the process, I would now offer some advice to prospective atheist parents:

- Clarify your desire to adopt as a family and seek council with a trusted therapist specializing in adoption.

- Read everything you can about adoption, attachment issues and legal barriers in your state.

- Do not let your lack of religious faith detour your goal.

- Join an online atheist & Humanist parenting group for (anonymous) support.

- Try respite care within a foster care agency first. By offering your services as a caretaker, you can learn what it’s like to help a child cope from a traumatic life event first hand. It’s not easy, but it’s rewarding. It’s also a way to dip your toes into the water of adoption.

- Be prepared to be rejected over and over (and over!). Don’t take the process personally.

My husband and I differ about whether or not to disclose one’s atheism to an agency. He believes it’s too soon in our society to be open about it entirely. But I think it’s our duty to be the change. If we don’t speak out, who will?

Before our adoption, we were concerned that, because of our lack of faith, our children might reject us. But our kids accepted our lack of religiousness without a second thought. In fact, they felt very relieved that they wouldn’t have to attend religious studies and meetings or be told what to believe in. Raised in the Bible Belt, these kids now have the freedom to choose about their own paths without judgment. We allow them to challenge our perspectives and debate their own ideas freely in our home, something they were unable to do in the past.

The best part about having a large blended family is that our support for one another helps us explore our own meaning of family; the diversity of everyone’s tragedies and personal challenges have made us stronger and more united. It is this deep resiliency that contributes to our universal happiness. The beauty in creating a family by sharing ourselves has been extremely rewarding. I want this world to be a better place for them and for our many generations of “Happy Gilmores” to come.

[Source: http://i.imgur.com/g9EURYU.jpg]

You might be wondering if our kids are atheists. Most of them are. But our oldest son spent many years attending friends’ churches just for the sake of debate. We focus on being freethinkers rather than giving them any declarative labels. Our kids all attended religious pre-school (it was the only local option) and/or other religious-based camps in the past and understand a variety of religious beliefs. Most of our kids have also attended Camp Quest, the secular summer camp. Some of them have now gone two years in a row! Both times, they came back from camp energized by their experiences, eager to share ideas and debate with their peers. We also attended the Reason Rally last year.

[Two of the Gilmore kids stand next to ‘Jesus on a dinosaur."]

Children waiting to be adopted need secure, happy and creative parents who will let them explore their own identities, deal with losses and grieve. While adoption has traditionally been the purview of religious families, non-believers need to jump into the mix. All children — especially older children — deserve a home, and secular families can do their part in providing homes for them. I encourage you to consider it as a way to really live out your Humanism.

Shares