Maureen Dowd had to get the flu to discover that she likes dragons. In an otherwise fairly silly New York Times Op-Ed column last Sunday on the pallidness of Washington, D.C., power plays compared to the bloody rivalries in HBO's "Game of Thrones," Dowd begins by explaining her initial resistance to the series, based on the novels of George R.R Martin. "I’m not really a Middle-earth sort of girl," she writes. "I had no interest in the murky male world of orcs, elves, hobbits, goblins and warrior dwarves."

The idea that epic fantasy is somehow a "male" genre is apparently entrenched at the New York Times. Most notoriously, critic Ginia Bellafante wrote a disgusted review of the series' premiere in 2011, implying that "the Dungeons & Dragons aesthetic" has no place in a high-class venue like HBO. "While I do not doubt that there are women in the world who read books like Mr. Martin’s," Bellafante wrote, "I can honestly say that I have never met a single woman who has stood up in indignation at her book club and refused to read the latest from Lorrie Moore unless everyone agreed to 'The Hobbit' first. 'Game of Thrones' is boy fiction."

As the author of a lengthy profile of Martin (the same one Dowd references in her column), I can offer eyewitness testimony to contradict that. The Martin book signing I observed in Pasadena, Calif., drew a crowd of about 300, and it was the most diverse group of readers – in race and age as well as in gender – of any bookstore event I've ever attended. (I wonder how Lorrie Moore holds up in that department.) But let's not rekindle the preposterously operatic outrage that Bellafante's misbegotten review provoked among fantasy fans. "Game of Thrones" has since proven itself a palpable hit with all kinds of viewers, HBO's biggest since "The Sopranos."

Instead, let Dowd's tale serve as a reminder: Not just that fantasy gets unfairly stereotyped, but that all of us, as readers, have stubborn ideas about what kinds of books we're going to like, and at least some of the time we're dead wrong. In a refreshing 1999 essay for Salon, writer Gavin McNett related how, while recovering from a wisdom tooth extraction, he sneakily began reading his girlfriend's copies of Diana Gabaldon's "Outlander" series: "I once carried a dogeared copy of Walter Benjamin’s 'Illuminations' through every punk squat in Europe," he relates, "and was now reading a historical romance novel."

And loving it. To his surprise, McNett, who had once read a generic regency romance for a college course and thought it "a rickety trellis of plot devices hung with obsolete undergarments and bad adverbs," found "Outlander" to be "a carefully written book, with three-dimensional characters inhabiting a complex, believable world." Gabaldon breaks with several established tropes of romance fiction in her saga, injecting lashings of history and action as well as a dollop of time travel. McNett followed his girlfriend in plowing through several more fat volumes of the "Outlander" books, which is currently being produced as a series for Starz.

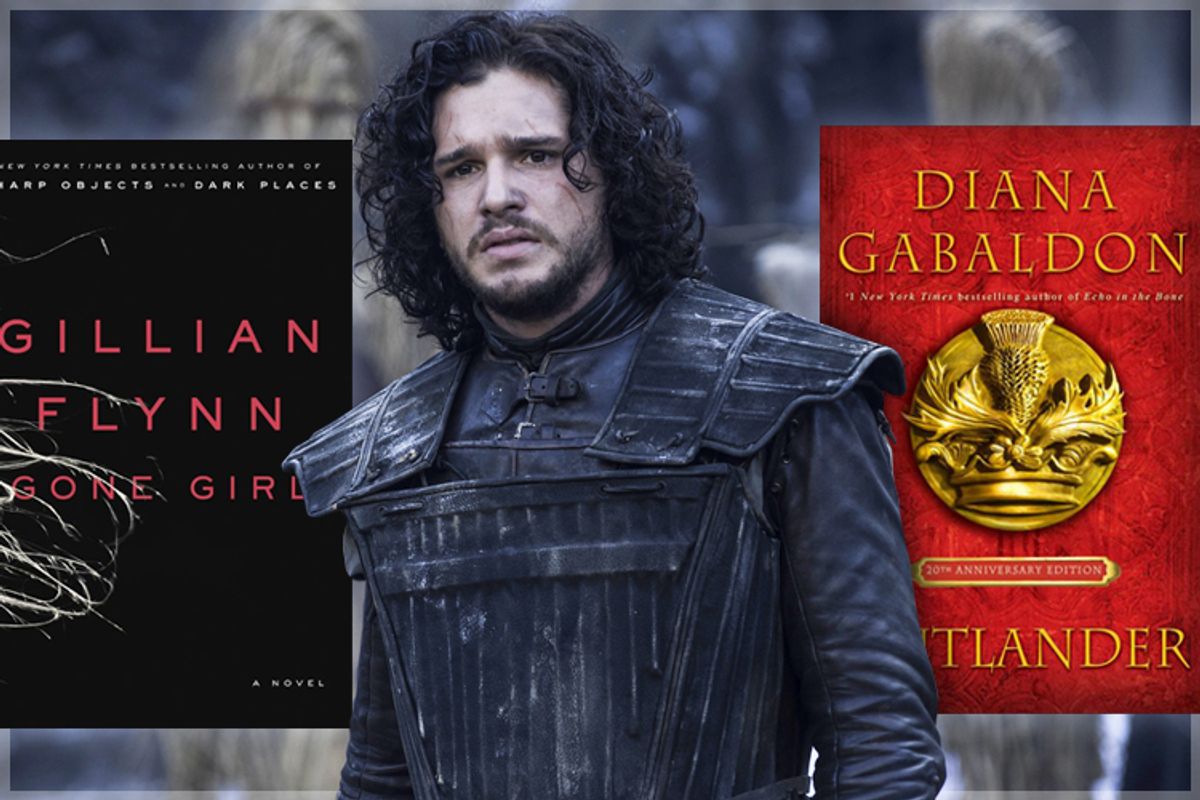

It's often the authors who choose to defy a genre's tireder conventions, as Martin did, who best succeed at winning a large crossover audience. The twist might be anything from Gillian Flynn's biting social satire in a thriller like "Gone Girl" to the lavishly entertaining plotting in a literary novel like Donna Tartt's "The Goldfinch." Every genre has authors who do this. And readers who can't get past their supposed aversions to dragons or sex scenes or coming-of-age stories – markers we come to associate with books that are "not for me" – stand to miss out on a lot. Yes, if you're partial to the trappings of a particular genre, whether it's the whiskey and wisecracks of a hard-boiled private detective yarn or the magical swords of epic fantasy or the exhaustively detailed mother-daughter-sister-friend relationships of women's fiction, then chances are you'll happily gobble up the weaker and more predictable examples of the form. But the best books in every genre have the capacity to delight far more readers than they currently do, especially since most of them will never be made into hit TV series.

There's something about a convalescence that softens up the staunchest prejudices. Both Dowd and McNett were sick when they ventured into new fictional territory. For me, in my mid-20s, it took a combination of illness and a broken heart to break my college-dictated literary diet of American modernists and fat 19th-century novels. I could eat nothing but Cheerios and read nothing but P.D. James' Cordelia Gray mysteries. I had not opened a detective novel since an Agatha Christie binge in my teens, and I had no interest in James's more popular character, Detective Chief-Inspector Adam Dagliesh. I now realize I preferred Cordelia because she was a young woman, unaffiliated with any institution, whose comfortless childhood, solitary nature and determination to unearth the truth were all traits I identified with. The melancholy, ruminative nature of the novels came as a revelation to a reader who equated mysteries with Christie's sprightly but ephemeral puzzles or the stunted emotional range of tough-guy noir.

In a world overflowing with books, readers understandably scan for traits they associate with their favorite kinds, but too often other traits become a reason to eliminate some titles out of hand. Sticking to a well-worn rut is easiest, but in addition to narrowing your taste, mind and imagination, it will cheat you of untold reading pleasure. I've learned to listen when friends insist that this or that specimen of a genre stands out from the crowd, which is how, even though I really couldn't care less about dragons, I ended up reading "A Game of Thrones" several years ago. I'm just glad I didn't make myself wait until I got sick to do it.

Further reading

Maureen Dowd on "A Game of Thrones" for the New York Times

Ginia Bellafante reviews the first season of "Game of Thrones" for the New York

Shares