I had a girlfriend in college. It wasn’t really working out. Mainly because she was seeing other people and I couldn’t be bothered to ask her not to. Being nineteen in 1989 meant a feigned indifference toward commitment of any kind. It also meant all your tunes were on cassette.

I had a girlfriend in college. It wasn’t really working out. Mainly because she was seeing other people and I couldn’t be bothered to ask her not to. Being nineteen in 1989 meant a feigned indifference toward commitment of any kind. It also meant all your tunes were on cassette.

She handed me a TDK and said, “listen to this.” I did, in the AV basement where I was splicing together a very important 16mm film that less than ten people would ever eventually see. The next day she asked what I thought. I thought the band was hard and raw. I thought they had an unusual sense of melody. I liked how the vocal lines often matched the guitar parts. She said that was good, because they were playing that night in Cleveland.

The venue was tiny, in the middle of nowhere. There were a dozen people inside, tops. The band came onstage to the same sort of applause that breaks out in a cafeteria when someone drops a tray. They were loud. Punishingly loud. I spent most of the show hustling the local sharps at pool, barely paying attention. The band seemed bored of themselves by the end of the third song anyway. After the set, they sat at the bar and drank for hours. All the way home my ears rang so loudly I couldn’t hear my own cynicism.

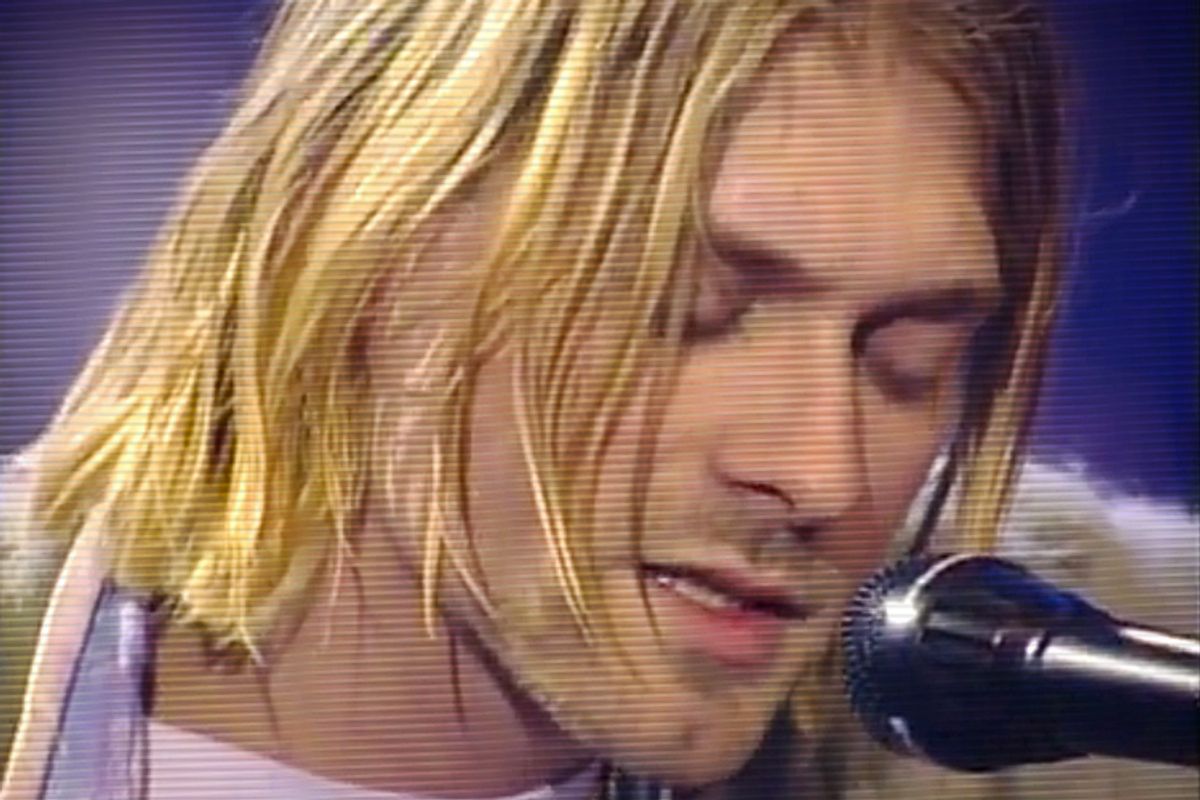

By now you’ve probably guessed that the band was Nirvana, and the cassette wasBleach. Kurt Cobain was 27 years old when he died and will be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame on the 20th anniversary of his suicide, which begs for some sort of analogy. But I’m not going to deliver it.

There is nothing to write about Nirvana that hasn’t already been written, no Kurt speculation that will shed light on his place in the pantheon of screamed lyrics and distorted guitars. Kurt remains beloved for his perceived authenticity, and perhaps his suicide feeds into that notion. Better to die depressed and strung-out than to break up the band and start recording electronica with Michael Stipe. Fans hate when their musical heroes evolve. Or, really, change at all. Kurt is a god because he never had the chance to change. He is revered because he chose a shotgun over disappointing us all by getting older and revealing himself as human.

No one will ever fill Kurt’s Converse Hi-Tops. Less than six months after his death, alternative replacements like the Dinosaur Jr. and Sonic Youth were rudely ignored while a massive search was conducted for the “next Nirvana.” They’re still looking. It was a crude notion that fatally misinterpreted the memo. Nirvana’s sound could have only come out of rain-pounded Seattle and the cultural wasteland that was the Pacific Northwest in the depths of Clinton-era self-satisfaction. It could only have been produced by a trio, fronted by a reticent, self-loathing left-handed guitar player whose basic message was, “you are not alone.”

But we are alone. Because it’s two decades after he intentionally left us.

What remains? The Foo Fighters put out the occasional tepid album. A long-rumored comprehensive Nirvana boxed set is tied up in litigation. Infant Frances Bean is now not only an adult, but a quasi-celebrity. And while not busy locating Malaysian Air 370, Courtney Love continues to collapse in on herself in a way that’s vaguely reassuring.

I probably know less about Kurt and his legacy now than I did twenty years ago. Maybe the true meaning of Nirvana cannot be expressed in words, because if there is any meaning at all, it exists in the brain of a fourteen year-old hearing “I swear I don’t have a gun” for the first time. The big secret of grunge was that it didn’t describe a style of music, fashion, or even attitude. It was the line where the misfits finally broke through. And Kurt was the head misfit. Small, shy, singing about pain and alienation in a dirty sweater. Beaten up and belittled in high school. A heroin addict who founded a strain of alt-metal that had once been the sole provenance of gearheads, dopesmokers, and those who thought Van Halen never took their shtick far enough.

It’s been speculated that Kurt took his life because he could no longer stand the adulation of dudes who tended to fill arenas and buy tour swag and gobble up compact discs. Even while hiding behind goatees and knit caps, Kurt knew most of his fans were variants of the same kids who mistreated him in school. And now he was getting rich singing to them. He certainly wasn’t singing for them, even if many of his lyrics were aimed smack between their eyes. Here we are now, entertain us. Kurt couldn’t handle entertaining his past any more than he could face his present.

Nirvana remains relevant because they arrived at the exact moment the musical paint needed to be stripped, the light-show extinguished, the pomp skewered. A cheap guitar, stubble, and a genius sense of disaffection galvanized a generation. Kurt wasn’t a glam rocker or pretty English boy. He didn’t wear makeup or front a group with synchronized dance moves. He was raspy-voiced and vulnerable, singing about not liking himself a whole lot, and not liking you very much either. Nirvana conquered a bloated pop scene with a sound that had previously been restricted to basements and trashy dives. One minute it was melodic thrash, and the next Lollapalooza was a verb and everyone’s father had Nevermind cranked in their Lexus. It made no sense, but neither did anything else in the early nineties.

What would Kurt be up to if he were still alive? Promoting the Grunge Reunion Tour at forty-seven, bearing his soul and scarred wrists in front of a sea of grey ponytails? Or would he have long packed it in and moved to Montana to live as a hollow-eyed recluse? In either case it’s certain that Kurt would have had an opinion on being included as part of any anniversary, let alone an induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Mr. Cobain would have hated every second of it.

In terms of our lionized punk-poets, we wouldn’t have it any other way.

Shares