Who'd have guessed that shepherding could be quite so interesting?

Evie Wyld's new book, "All the Birds, Singing," which comes out today, takes as its milieu a remote British island where Jake, our female protagonist, drinks and herds sheep. She does the former better than the latter, as some malign force -- local kids, perhaps? -- is brutally murdering her sheep. Jake feels compelled to figure out just who is doing the killing all while revealing the darkness in her own past only bit-by-bit, in a manner that's at once confusing and utterly gripping.

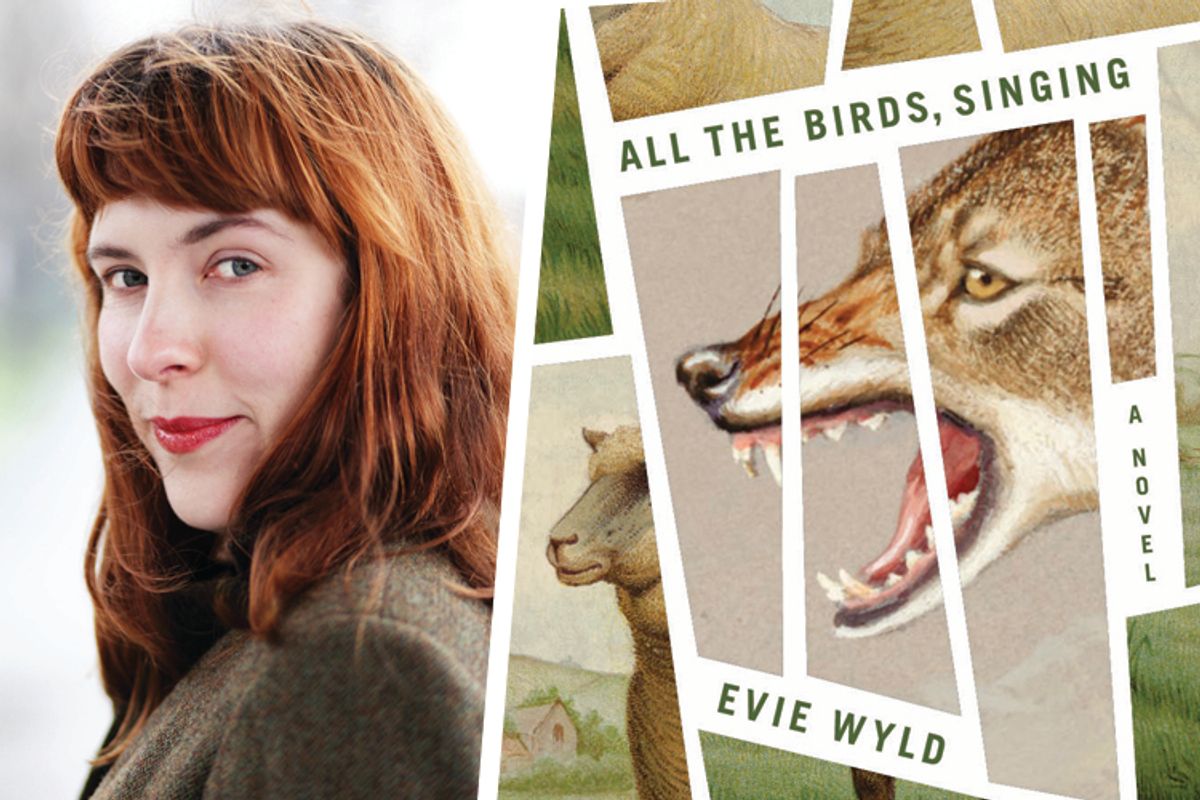

"All the Birds, Singing" raises the question of what, precisely, is "genre" and what is "literary." The book, whose author runs a small bookshop in London, has the brisk pacing of a well-thumbed pocket paperback found in a summer cottage, and yet it's the sort of book that gets listed by British newspapers (the Guardian, New Statesman, Independent, and Observer among them) as a best book of the year and gets a push from a highbrow publisher (Pantheon). The success, last year, of "The Goldfinch" was a perfect test case: The book was rife with allusions, sure, but was as compulsively readable as a Harry Potter novel. Wyld's trick has been to present the novel as the story of a shepherd dealing with an immediately affecting work crisis, but to very slowly complicate it; the mystery of what's going on with the sheep, were it the book's only subject, would make for a fun read on its own. But the sheep are only the beginning.

The new book, Wyld says, is meant to be viscerally affecting, not just admired: "I knew I wanted to write something frightening," she told Salon. But that effect comes not solely via what happens in the plot but by how it's told. Wyld said that the editing process "became like a [math] problem and I had to remove quite a lot of work that I was really proud of because it just didn’t fit any longer with the structure." What remains is based in part on surrealistic memories to set the scene in her novel's present day: The island is based on Wyld's childhood memories of visiting a British island where "there are still rumours all these years later that the puma bred with a wild cat and produced killer beasts." The sheep, too, came from life: "I’m still not their biggest fan," she noted, after a hiking trip years ago brought her into contact with sheep that managed to get themselves tangled in brambles and resisted her help. Further research among shepherds in Wales indicated just how vulnerable sheep are: "The main thing they do is find different ways to die. Disease, weather, mink, foxes, getting trapped, starving to death, overeating and then falling over. Many different ways to die if you’re a sheep."

Thus, when it came time to write, "it was like I was resisting sheep as much as possible," and she has resisted to this day the opportunity to shear a sheep, despite many opportunities to lend her work a bit more verisimilitude. The muteness and unfeeling nature of the sheep -- so unlike dogs -- is as authentic as it needs to be: Wyld's book could take place anywhere and with any set of identifying details. It's not the shepherding that's interesting at all, really, but the mute and vulnerable sheep are the perfect backdrop for Wyld's particular nihilism and the way in which she tracks her protagonist's isolation.

"I noticed it most when my father died, how separate we all were from each other. You come to realize even surrounded by people that everyone is alone," she said. "And I don’t mean that to sound sinister. I think it’s one of life’s great strengths." She'd been isolated, too, with a case of encephalitis as a child: "My convalescence meant being on medication that kept me very quiet and dopey. I think I lived a fairly solitary childhood in a way and I liked it like that. I was more interested in my imagination than reality."

No wonder that the island at the center of "All the Birds, Singing" feels weirdly out of time, or imagined -- it's a digestion of experiences from Wyld's own life, reimagined and recast in opposition to a horrific past. As for the question of whether her book is meant to be devoured or savored, treated as highbrow lit or a ripping read, Wyld demurs. "I don’t believe in an ‘ideal reader’ like some writers do, I think that the point of reading, and of writing is that depending on your experience of life, everyone will come away with a totally different version of a novel. I think that’s a good thing."

Shares