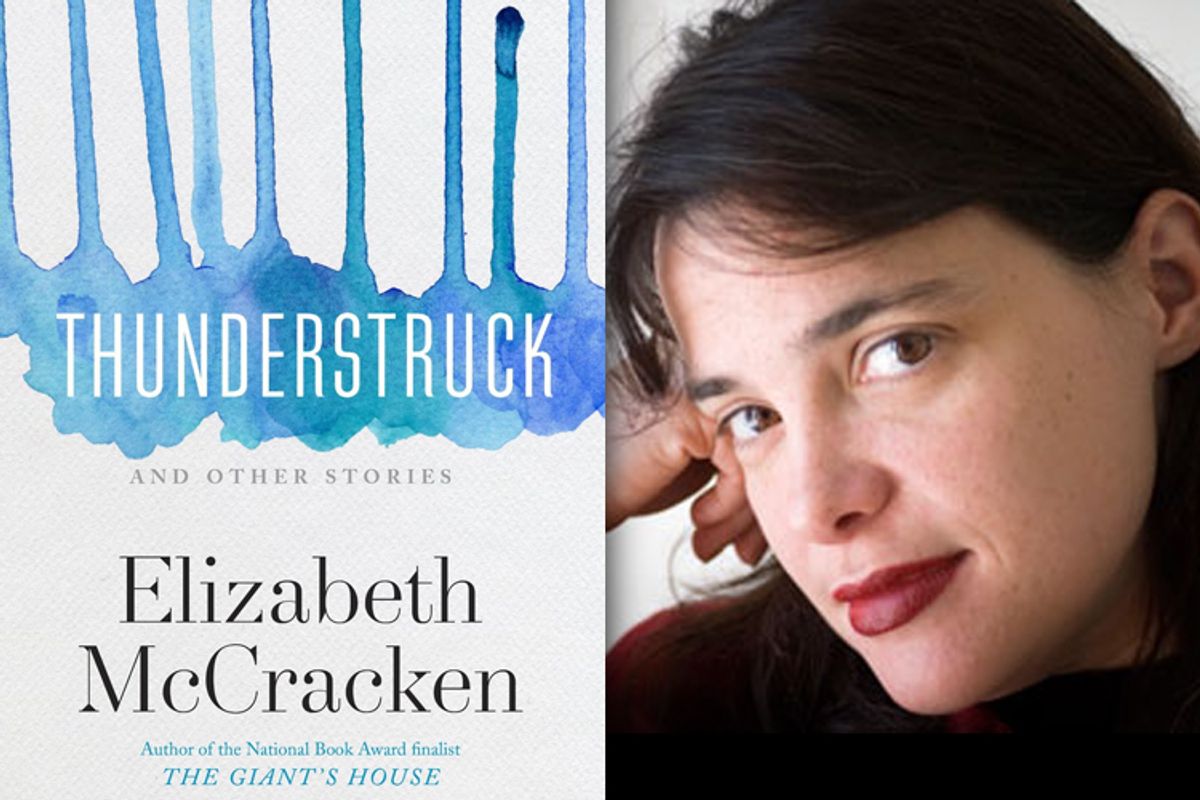

Elizabeth McCracken’s writing is characterized by humor, gasp-worthy metaphors, and a careful, playful attention to language. She is the author of two novels ("The Giant’s House" and "Niagara Falls All Over Again"), a memoir ("An Exact Replica of a Figment of My Imagination"), and two story collections, the latest of which, "Thunderstruck and Other Stories," comes out Tuesday from the Dial Press. Each of "Thunderstruck’s" nine stories is a storm: delightful and destructive, packed with electricity, fascinating to watch unfold from the safe harbor of a comfortable chair.

McCracken, a former librarian, currently holds the James A. Michener Chair in Fiction at the University of Texas, Austin. She’s known among students for her insightful and utterly enjoyable workshops and classes — not to mention the police whistle she often wears around her neck. I talked with Elizabeth over email and in her book-lined campus office.

"Thunderstruck" is your fifth book and second story collection. Has your writing process changed much since publishing your first book, the collection "Here’s Your Hat What’s Your Hurry," in 1993?

I used to be a writer with superstitions worthy of a professional baseball player: I needed a certain desk chair and a certain armchair and a certain desk arrangement and I could only get really useful work done between 8 p.m. and 3 a.m. Then I started to move, and I couldn’t bring my chairs with me. Then I began to live with other people (husband, children) and so working weird hours while alternating bottles of beer with cans of Diet Coke (which is pretty much how I wrote "Here’s Your Hat") became impractical. Now I write during daylight while drinking coffee and cans of sparkling water. I’ve been reunited with my favorite work chairs, though. I still think they’re lucky.

Where and when did you write the stories in "Thunderstruck"?

Variously, though mostly they’re recent. “Juliet” is the oldest story in the book. I wrote it in the mid ‘90s, when I was circulation desk chief at the Somerville Public Library. Three of the stories are part of a failed novel that broke into pieces when I cast it aside 10 years ago, though the material’s been considerably reworked. Three of the stories I wrote when I was on leave from teaching in the fall of 2012 — I actually wrote several more, but the other stories didn’t make the cut, and I’m still working on some other stuff I wrote that semester. I was probably insufferable on the subject of hard work in my spring workshop of 2013, I worked so hard while I was on leave. That’s another way my writing process has changed; now that I teach full time, I work incredibly long hours when the semester’s over. Geographically the stories were written in: Iowa, Paris, Berlin, Denmark, Cambridge, Mass., Austin, Texas. I might have worked on one a little in Kilkenny, Ireland, but probably to no good effect.

You’ve said you see a lot of workshop stories in which the coffee’s always cold and the beer’s always warm. What tics have you learned to watch out for in your own writing?

Dozens. I can only list the ones I recognize: lots of characters standing up next to other characters in bed, haircuts (one of your Michener colleagues mentioned this to me, but I’d already clocked it), examining forks. Revising stuff lately I was shocked to see how often my characters scratched their ankles, felt their feet, and touched their own ears. Well, I guess fictional characters, like everyone else, have mostly given up smoking and have to do something else. Maybe next I’ll give them all crochet hooks and lengths of yarn. Lot of facial hair, too, and I seem to be unable to introduce a character without noting eye color and relative height to everyone else in the room.

Anyone who follows you knows you adore Twitter. What’s the appeal of tweeting, for you?

I love the whole genre of — what’ll we call it? Shortest form narrative? Church message boards, fortune cookie fortunes, aphorisms, Al Jaffe’s Snappy Comebacks to Stupid Questions, books of quotations, famous telegrams (“How old Cary Grant?” “Old Cary Grant fine. How you?”) dirty jokes on cartoon postcards, New Yorker comic captions, hokey one-liners, knock-knocks. So there’s that: I love strange compression out of context. Twitter’s also interesting as a vehicle of affection: I like how strangers can be fond of each other, even sentimental. You and I are both fans and followers of the peculiar and wonderful Duchess Goldblatt account — purportedly an 81-year-old fictional European duchess — which is on the one hand flat-out funny and on the other hand full of pet names, declarations of love. She is very sweet to people she likes, which is one of the reasons I wouldn’t want to know her identity. A secret admirer is never so delightful once unmasked.

Have your literary influences changed since you started writing? Do you find yourself, as your career progresses, accreting influences, adding to the list of writers who inspire you? Or do you feel like you’re less easily swayed now than when you were on book No. 1 or 2?

When it comes to other people’s writing, my older influences are more powerful than more recent ones, partially because I’m now more worried that I’ll suddenly accidentally steal something from another writer. Maybe also because — and I lament the loss of this — when I was younger the concrete of my writing was still wet, and it was easier to make an imprint. But extra-literary influence is another question, and I feel like that changes constantly — the photography of Francesca Woodman, the paintings of Julie Speed, the comics of Lynda Barry — though of course Lynda Barry is also a brilliant writer. She’s also an old influence: Reading her work in the Village Voice when I was young had a big effect on me.

Humor is a hallmark of your writing. Where does your comic sensibility come from, and why do you think humor finds its way so naturally into your writing?

I don’t know how to get it out. I mean, I wouldn’t want to: It’s a native species. This is a topic I’m quite boring about, when I teach: some young writers mistake humorlessness for seriousness. They remove all traces of humor as though with a scalpel, and the patient doesn’t survive the surgery. On Twitter I was complaining about this, and several writers responded, “But I don’t like jokes; I don’t know how to make them.” Well, life likes jokes, life is constantly making jokes, even at the most inopportune moments. Probably particularly then. As you well know, from your own splendid work: an appreciation for the absurd throws everything else into relief: sadness, beauty, emotion. Humorless fiction is a sealed room. There may be meaning inside: the pitch dark will render it meaningless. As for humorless human beings — I don’t even know how to talk to them. They’re the first people I plan to eat in the lifeboat I’m certain I will some day end up in.

Do you have a favorite story from "Thunderstruck"?

No. I have ludicrous little points of pride in all of them, and am aware of their deficiencies, too. “Juliet” is probably my least favorite, just because I wrote it so long ago — I can’t remember its infancy, I guess I mean, when it was little and helpless, and now I’m just stuck with this awkward teenager.

A number of stories in "Thunderstruck" reference fairy tale tropes: We hear the phrase “once upon a time” a few times, mentions of little girls and boys, old grandmothers. What’s your relationship to fairy tales and how do you think they’ve affected your storytelling?

The uncanny, bodily transformations, love, family you can trust, family you can’t, cannibalism, the forest, physical oddballs — what’s not to love? These are my basic preoccupations, though maybe they’re merely human preoccupations. Certainly we’re living in a great age of fairy tales at the moment. Allan Gurganus, my first teacher in graduate school, talked a lot about fairy tales, and maybe that was the start of my interest as far as fiction goes (I still would do anything Allan told me to do) — though I do remember being a kid, absolutely obsessed with them, particularly a pair of books illustrated by woodcuts of “Little Red Riding Hood” and “The Three Billy Goats Gruff.” I loved all my books of fairy tales, but I favored the ones with frightening illustrations—I had a big volume of fairy tales that was illustrated with really pretty paintings, and I remember my dissatisfaction with the pictures for “The Seven Swans,” in particular. Too much beauty, not enough monstrousness! I have a love of the monstrous bordering on beauty, I guess, that has worked its way into nearly everything I write. It’s certainly particularly loud in my first novel.

And finally, is there anything you are working on next?

Oh, a thing. It’s a thing. That’s probably as much as I’ll say.

Shares