Hello, my name is Scott Rodd, and I'm calling to inquire about internship and employment opportunities at [Insert Your Publication Here!]. Do you have a moment to speak with me this afternoon?

Fetching little salutation, is it not? Those few lines were refined down to the slightest pause and intonation during months of phone-schmoozing with smart, hardworking Americans employed at magazines and newspapers around the country. My poor roommates — trying to bask in their unfettered college bliss, untroubled by the thought of cover letters and job prospects — could probably recite these lines from memory by the time I took off from school at the end of December, down to the slightly higher register I use when talking on the phone with potential employers (or my grandparents).

Responses to my spiel ran the gamut. There were the exceedingly enthusiastic office managers, such as ________ at the New Republic: “It's so great you're interested in working for us! Unfortunately, our internships are unpaid, but it's well worth it! I started as an intern here myself!”

Then there were the overworked, underpaid staffers, such as ________ at Los Angeles magazine, who saw eager internship candidates as tinder for their fiery wrath: “You're seriously calling for information about internships? When you could have just sent an email? Not to be rude, but I can't be bothered with these kinds of questions. Do you think I have time to just sit around and talk to everyone who wants to work here? Do you understand how busy I am?”

Most responses fell somewhere between these two extremes — professional, curt, yet sympathetic to my desire to work in the industry. (My brief interaction with Los Angeles mag, I am happy to report, was the only time I'd been so thoroughly torched.) I hounded just about every publication I knew, and even tried a number of places I hadn't heard of until deep in the trenches of the job hunt. All of which — obscure or big-time — rejected me roundly or gave me the run-around until I (1) harangued them to the point where they had to reject me, (2) was led through a telephonic maze resulting in a terminal dead end, or (3) was promptly escorted out of their NYC offices when I showed up unannounced (which, in all fairness, only happened once).

*

The number of recent college graduates who are out of work and living at home in this country, as you may know, is nothing short of alarming. In a recent report on young adults and debt, Richard Fry of The Pew Research Center determined that in 2011, 45 percent of recent college graduates (ages 18-24) were living at home, compared to 31 percent in 2001. I had no interest, however, in contributing to the trend of the “Boomerang Generation.” With graduation on the near horizon this fall (I graduated in December), I resolved to live above the fray. I resolved to find a job.

But not just any job. I wanted to work at a magazine or a newspaper — that is, I wanted to work with words, in some capacity. That's what I told one of my roommates, Michael, and his girlfriend, Loren, when they asked what I wanted to do after graduation.

“You mean, like, write books?” Loren asked.

Not exactly, I said. Think of it this way: if there are words on a page, whether it be on paper or a screen, there has to be a person behind it. Someone had to come up with those words to reach whoever is on the other end reading them. Words are all around us — it can mean writing just about anything.

Loren was searching through a drawer in our kitchen when she pulled out a little white booklet. “Like a toaster manual,” she said.

This became a running joke among my friends — that I would end up doing some sort of instructive, technical writing on how to avoid burning toast or where to not apply some topical cream. It was a joke that I encouraged by participating — after all, it would only be offensive if it were true. I was graduating summa cum laude with departmental honors, made the dean's list every semester, and held two internships abroad. I had a short story forthcoming in a nationally distributed literary magazine, participated in two undergraduate literature conferences, and had a wide breadth of employment experiences (including an internship at a small publisher). I was, to use HR argot lifted from a recent meeting at my school’s career center, an “extremely motivated candidate” who was “highly suitable for the positions” I sought.

At the top of my list were publications like the New Yorker, Time, Esquire, the New York Times, and Harper's, among others. Harper’s may have been the place I was most interested in — they offered a three-month, highly intensive internship that involved fact-checking, copy editing, writing and generating ideas for the magazine. I'd applied for their summer internship the previous year, spending a month poring over six pages of application responses, and received the following personal response:

Dear Scott,

My colleague ________ and I want to thank you for taking the time to complete the Harper’s Magazine internship application. I'm sorry to say that you have not been chosen for the program, but the thoroughness and intelligence of your application were greatly appreciated. We wish you the best of luck for the future.

One close friend was fairly candid with his skepticism about the internship. What're they gonna have you doing there, he said, scrubbing butts and fetching coffee? But I didn't let his cynicism faze me — I revised and resubmitted my application at the beginning of October. Even if I was scrubbing butts, I thought to myself, these were Harper's butts we were talking about.

I took the next few weeks to tighten my résumé, draw up a cover letter template, and polish some writing samples. For the publications that openly solicited applications, like the Atlantic, the Nation, and Wired, I submitted my materials, careful to tailor each submission to the specific publication — for example, by inserting a quote from the magazine's mission statement page in my cover letter.

For the places that didn't openly solicit applications, it was simple: I called them.

New York was the first magazine I called, because their number was openly listed on their contact page. I reached the front desk, and the receptionist transferred me to the woman in charge of hiring.

“Hello, this is ________.”

“Hi,” I said, “I — I was transferred to you because I was interested — well, I am interested in an internship at New York.” I stumbled through a brief, clunky bio of myself -- my name, where I studied, my areas of interest — and asked what I needed to do to apply for an internship.

“You'll need to send a résumé, cover letter, and three clips to ________@NYMag.com.”

“OK, and is there a deadline for the application?”

“The sooner, the better for the spring session.”

“Great, I'll get right on that,” I said. “Thank you for your help.”

“Yep, take care.”

Was that all it took? A simple phone call and I was on congenial terms with someone on the inside? On a kick after how smoothly my call went with New York, I decided to tackle another name at the top of my list: GQ. Under the Media Kit tab on the website for Condé Nast, the parent company for GQ and a number of other magazines, I found a list of editors and publishers with their contact information. I dialed the number for the associate publisher at GQ. His assistant answered, and we spoke for a few minutes about internships at GQ.

“So, who's your contact at GQ?” the assistant asked.

“My contact — ?”

“Yes, I assume they gave you this number.”

“I actually don't have a contact at GQ,” I said.

“You know this is a direct line to the Associate Publisher, right?”

“Right.”

“So, how did you get this number?”

Truth is, I told him, I found it online. At this point, the assistant’s voice took on a different tone — more officious than when we were chatting about internships.

“Well, I'm surprised they make that information available to the public.”

It was at this early point in my search that I first asked myself, Was my cold-calling showing boldness? Was I being proactive and outgoing here? Or was I simply grouping myself among the wingnuts who called to pitch stories about, say, Government Conspiracy? Was this helping me stand out among other potential candidates, or was I blending in among wackjobs with access to a landline and too much time on their hands?

Still, I pressed on. I called a few more Condé Nast brands, like the New Yorker and Ars Technica, and moved on to other publications on my list. Most reputable publications, it turned out, weren't as easy to reach as the brands under Condé Nast. Not only do they avoid openly listing phone numbers, they often set up lines of defense — such as computerized option menus or live receptionists — to deflect unwanted calls if you do get their number.

Some lines of defense proved impenetrable. The worst were receptionists who, I came to suspect, were stationed somewhere far from where the real action took place — somewhere remote and probably not very well ventilated. These people were almost always ill-humored and curmudgeonly.

When I called Rolling Stone, for example, I started in on my usual spiel, but at the mention of “internship,” the receptionist interrupted me.

“You're gonna have to go to their website,” he said.

Not the website or our website, but their website.

“I checked the website,” I said, “but I still have some questions. Is there someone I can talk to about — ”

“Like I said, it's all on their website.”

“Right. Can you just connect me with the editorial department?”

“I wouldn't even know who to transfer you to,” he said. “Plus, they’re just gonna tell you the same thing I told you — check the website.”

Click.

*

By mid-November, I'd steadily worked through most second-tier publications on my list — Newsweek, Vice, Village Voice, LA Times, etc. — and started applying to reputable news websites, like Salon, Huffington Post and Politico. At this point, I'd gotten pretty good at navigating through whatever lines of defense I encountered when calling these places. Computerized directories were a cinch, and live receptionists offered the opportunity to evoke sympathy, exchange small talk, maybe even share some light telephonic flirtation — any proficiency in schmoozing would get you a decent shot at being connected with the editorial department. Other times, it took just plain wit — for example, when I called InterActiveCorp., the parent company for the Daily Beast.

“Good afternoon, InterActive,” the receptionist said. “How may I help you?”

“Hi, can you connect me with the editorial department at the Daily Beast?”

“Do you have the name of you person you're looking to speak with?” she asked.

“I don't, sorry.”

“I apologize, sir, but I can't transfer any calls without a specific name. Is there anything else I can help you with this afternoon?”

“No, thanks,” I said.

I hung up and opened the Daily Beast's homepage. I perused some articles until I found a suitable name and title. I dialed the main line again.

“Good afternoon, InterActive. How may I help you?”

“Hi, can you connect me with Daily Beast Associate Editor ________?”

“Please hold.”

I was in — but getting through this first line of defense guarantees little. Instead of reaching ________, I was connected with an assistant who, though sweet, proved unhelpful. I asked about internships, and she struggled to provide even the most basic information. She put me on hold as she leafed through a company directory, but apparently found no one suitable for me to speak with.

“Did you try emailing, maybe, internships@thedailybeast.com?” She asked the question with a tone of hopeful uncertainty, which I knew was probably the best I was going to get here.

When I emailed internships@thedailybeast.com later that day, I received the following, immediate response:

The original message was received

from m0043384.ppops.net [127.0.0.1]-- The following addresses had permanent fatal errors--

<internships@thedailybeast.com>

(reason: 550 5.1.1 User unknown)

I sent out a flurry of applications leading up to Thanksgiving in order to take some time off from my search when I went home for break. I spent those few days binge eating and giving curt, open-ended answers to my parents' questions about prospects after graduation. Just before returning to campus, I received a stock email from Harper's, thanking me for applying to the internship program (again), but regretting to inform me that I had not been accepted.

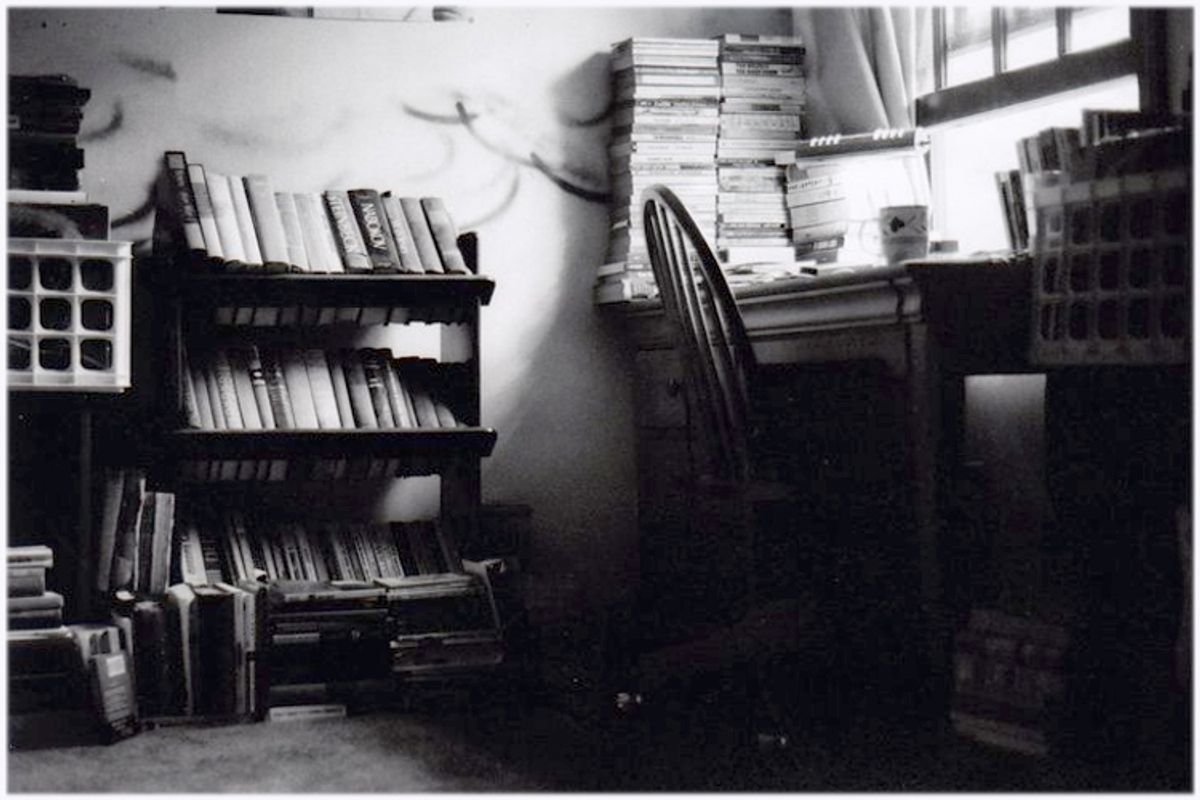

Anticipating that this response was only the precursor to a wave of rejections, I braced myself by increasing my application output. After class on M/W/F, I'd bring my lunch to the English Department lounge and comb through endless Contact Us pages, gathering phone numbers and email addresses until I had to go to work at the Writing Center. On T/Th, days that I didn't have class, I'd sit in the common room of my suite in boxer shorts, revising cover letters and cold-calling publications until lunch (or until I had to put pants on, like when the cleaning lady came in). I applied to regional magazines like Chicago, Cincinnati, and Indianapolis Monthly, as well as city-based news sites like Gothamist and Philly.com. I even sent my resume to a handful of music publications, like Spin, Pitchfork, Billboard and, on a whim, The Source and Vibe. To offset the anticipated pang of rejection, I needed to keep the application process a zero-sum game: For every door of opportunity that closed, a new one had to be opened. Only later would I realize that most of these doors closed softly, unnoticed — the majority of publications relying on the tactful passage of time to deliver rejection.

With a week of classes left, and the stress of finals beginning to mount, I had nearly reached the end of my rope. One evening, after alternating between studying for European history and emailing editorial assistants, I lay in bed with a pillow covering my face to block out the overhead fluorescent light.

“Rough day?” one of my roommates, Conor, asked as he walked in the room.

I let out a muffled groan from under the pillow.

“So, who had the pleasure of receiving your application today?” he asked.

“Buzzfeed,” I said through the pillow. “They have an opening for a food intern.”

“Food intern?”

I pushed the pillow aside and sat up. “I said in my cover letter that I wrote an essay on Mediterranean food for one of my classes.”

“Did you actually write an essay on Mediterranean food?” Conor asked.

“I ate tapas in Spain once.”

“So, you lied in your cover letter.”

I lay back down and, before replacing the pillow over my face, said, “I draw a distinction between lying and desperation.”

*

A week and a half later, classes had finished and finals were over — I was officially a Bachelor of the Arts. My roommate Nick and I stuck around on campus through the week, mainly staying in and drinking 40s. We were flat broke, so when we did go out, it wasn't to the bar but a friend's place on Water St., where we drank beer from a leftover keg stowed in the shed.

Luckily, Nick and I got paid at the end of the week. The U.S. Army deposited $300 into Nick's bank account; the Susquehanna University Writing Center, $26.70 into mine.

And then, unable to postpone the inevitable any longer, I drove home, exactly where I vowed I wouldn't be when I finished school. And I wasn't just breezing through for the holidays before returning to my busy, independent life — I was there indefinitely, with anywhere and nowhere to go.

I was reluctant to look for a job -- honestly, I was reluctant to unpack -- but it was inevitable in the face of my pressing financial situation. I printed a half-dozen résumés and set out on foot around the town center. I had to find work at the right sort of place — somewhere that my existing skill sets had application, sure, but just as important was finding a place where there was little chance for promotion or upward movement. Positions with the terms associate or junior in their title, for example, were out — those prefixes could easily be dropped, leaving me with little choice but to ascend to the next rung. I didn't want to succeed, I didn't want to move up — not here, at least — because moving up meant remaining in place. A tree can only grow tall by planting roots. I was content to be a low-lying bush, exposed to harsh conditions without the protective foliage of a fancy title. In fact, I wasn't even a bush: I was a tumbleweed in wait.

The first place I applied to was called La Petite France, a French bakery with aesthetically mismatched mugs and plate ware. I sat down with the owner and she asked me about my experience in food service. She was a small woman with a heavy French accent who, I could tell right away, was shrewd and disciplined in all matters of business. I talked her through the employment experiences on my résumé, casually digressing from time to time to note some additional accolade that was listed. Did I mention I graduated summa cum laude in December? With departmental honors? Oh and those two internships — they were in Dublin. As in, Ireland. And my GPA? A mere —

“Yes, good — and do jou know how to vork a commercial dishvasher?”

*

It took neither very long nor a four-year degree to figure out that the trick with the small Champion dishwasher in the back of the bakery was to front-load mugs and cups and keep the plates toward the back — otherwise, water didn't spray evenly over all the dishes. When scrubbing pans with layers of baked-on egg-wash, there was no trick. Just pure elbow grease.

When you are starting on the lowest rung at a job, there is little opportunity to do the “right” thing — only the opportunity to not screw up too badly. You also assume the responsibilities that none of your coworkers want to do — the kind of dirty, prideless tasks that come with the territory of any low-wage job. On my second day of work, standing behind the counter, I witnessed a young girl rise from her chair and vomit in the middle of the bakery's seating area. Her mother had just bought the girl a second chocolate croissant, which was now on the floor in a warm pile of slush. My coworkers and I gathered in the kitchen and silently exchanged glances.

“So, who's gonna clean it up?” one of the girls asked.

“I don't know,” said another girl. “I mean, what do you guys think?”

We resumed our exchange of silent glances. I appreciated the gesture, at least, of them trying to make this look like a democratic process.

“Where's the mop?” I said.

*

Do only good things, as they say, come in pairs? Doubtful, because scooping up half-digested croissants off that busy bakery floor wouldn't be the last time I'd encounter puke that week. On New Year's Eve, shortly after the stroke of midnight, I found myself on my hands and knees in a tiny Queens bathroom, hunched over a salmon-pink toilet bowl. My folded body blocked the doorway, so not only did I barge in on my friend while she was using the bathroom, she now had to witness my desperate purging.

“I didn't think you drank that much last night,” my friend Martha said the next morning. A group of us were on the living room floor of the apartment, nested in piles of blankets, unwilling to get up and face the day. I didn't think I drank much either — at least, not that I remembered. It must have been one too many gin and tonics, or the champagne when the ball dropped — the carbonation probably upset my stomach. As we looked through pictures on our phones and pieced together the night, however, the list of culprits began to grow. It could have been the Modelo, or the vodka orange juice, or the Coquito, or the Prosecco, or the Colt 45...

What made the trip to NYC feasible was an unexpected bonus check from my summer job and some Christmas cash from the family. I arrived in the city a few days before New Year's but had to limit my expenditures to public transportation and cost-friendly activities. I explored Central Park and walked the aisles of used book stores, fighting the urge to take out my wallet as I perused the shelves. When my buddies made their annual trip to the Turkish baths on 10th Street, I visited the Met, where I elected to pay five dollars for admittance instead of the recommended 15.

Some shrewd, pragmatic packing also helped make the trip manageable. I figured booze and food would be the major expenses in NYC — at least, the expenses I could try to minimize. I opened my dad's liquor cabinet, which was well-stocked yet untouched for the better part of 15 years, and perused the selection. A thick layer of dust coated the shoulders of the bottles, so I figured whatever I took wouldn't be missed. I stuffed a fifth of Gordon's London Dry into my bag next to the loaf of bread and jar of peanut butter that would suffice as breakfast and lunch during the trip.

In addition to these provisions, I packed a jacket and tie in my bag, which wasn't just to look good when I got soused on New Year's. With most of the publications I applied to headquartered in NYC, I thought the trip might be a good opportunity to put a face to the résumés I'd carpet-bombed the city with. In the days leading up to the trip, I restarted my telephone campaign, but this time with a new addition to my pitch — not only was I a recent graduate and eagerly searching for a job, I would also be in New York City on New Year's.

At the time I was convinced that, had I not stood out as a candidate before, this would somehow raise me above the rest of the field.

I decided to limit my calls to the places I'd already established a congenial rapport with, or that, at the very least, seemed like the kind of places that might treat me with some dignity — as someone searching and earnest, someone vulnerable to rejection.

The first person I called was the woman I had spoken to previously at New York. When I reached her voicemail, I left the following message:

“Hi Ms. _____, this is Scott Rodd. We spoke — well, what must've been a few months ago — about internship opportunities at New York. I wanted to touch base again and let you know that I am still very interested in this opportunity, and that I will be in New York City this week and would be more than happy to talk with you in person about my enthusiasm for working at a publication like New York.”

The voicemail I left with Ms. _____ served as a template for messages I left on answering machines all over Manhattan. Part of me feared that I'd come up on these places' radar as some semi-qualified gnat who kept buzzing around and wouldn't take a hint. My hope, though, was that my enthusiasm would be well received on the other end of the line, interpreted as coming from a guy who'd be a pleasure to have around the office and at after-work functions.

I didn't hear back from any of the places I contacted this second time around, and my messages, in the end, couldn't have been too well received. When I stopped at New York's offices on my way to Grand Central — a last-ditch effort before leaving the city — Ms. _____ offered enough of her time to tell me that my résumé had been received when I submitted it over a month ago, but that, sorry, she didn't have any time to speak with me about my enthusiasm for working at New York.

Was it possible that she didn't recognize who I was? After all, when I gave the receptionist my name, she dialed Ms. _____'s extension and said, “Hi, Ms. _____, there is a Mr. Ruff here to see you.”

“It's Rodd, actually,” I said.

“I'm sorry, a Mr. Rauld is here to see you.”

A look of confusion and — perhaps I'm reading into this too much — mild amusement came over the receptionist's face as she held the phone to her ear. The receptionist motioned for me to have a seat on the couch to wait. Ms. _____ entered the lobby and, when my allotted 20 seconds with her were up, I returned to the front desk to retrieve my jacket and bag. The receptionist offered her consolation.

“Well, that was quick.”

More likely than Ms. _____ not knowing who I was due to some flub on the receptionist's part is that she knew exactly who I was — that relentless gnat who showed the gall to actually come bumbling into New York's busy offices unannounced and uninvited. And part of me wondered, Could I blame her, really, for promptly showing me the exit with a clear indifference toward whether or not the door hit my ass on the way out?

So, as it turned out, New Year's would be the only time my jacket and tie were put to good use that trip. And while I started the night surrounded by close friends, holding a gin and tonic and dressed to kill, I practically wound up on death's doorstep — or, perhaps more accurately, death's bathroom floor. But if I didn't realize it then — half-conscious, purged and strung out on the cold tile — I am at least able to recognize it now. That from where I lay on the dirty bathroom floor of that cramped Queens apartment, I had nowhere to go but up.

Shares