The summer of 1989, at age 35, I sat next to my mother’s bed alongside my only sibling, my sister. Our mother was within weeks of dying, and because of the discovery of a brain tumor the previous Mother’s Day weekend, the capacity for language — her great and glorious talent — was abandoning her. But she looked at us hard that day and gripped my hand with surprising force for a woman nearing her final breath.

“You girls,” she said to us. “My greatest accomplishment.”

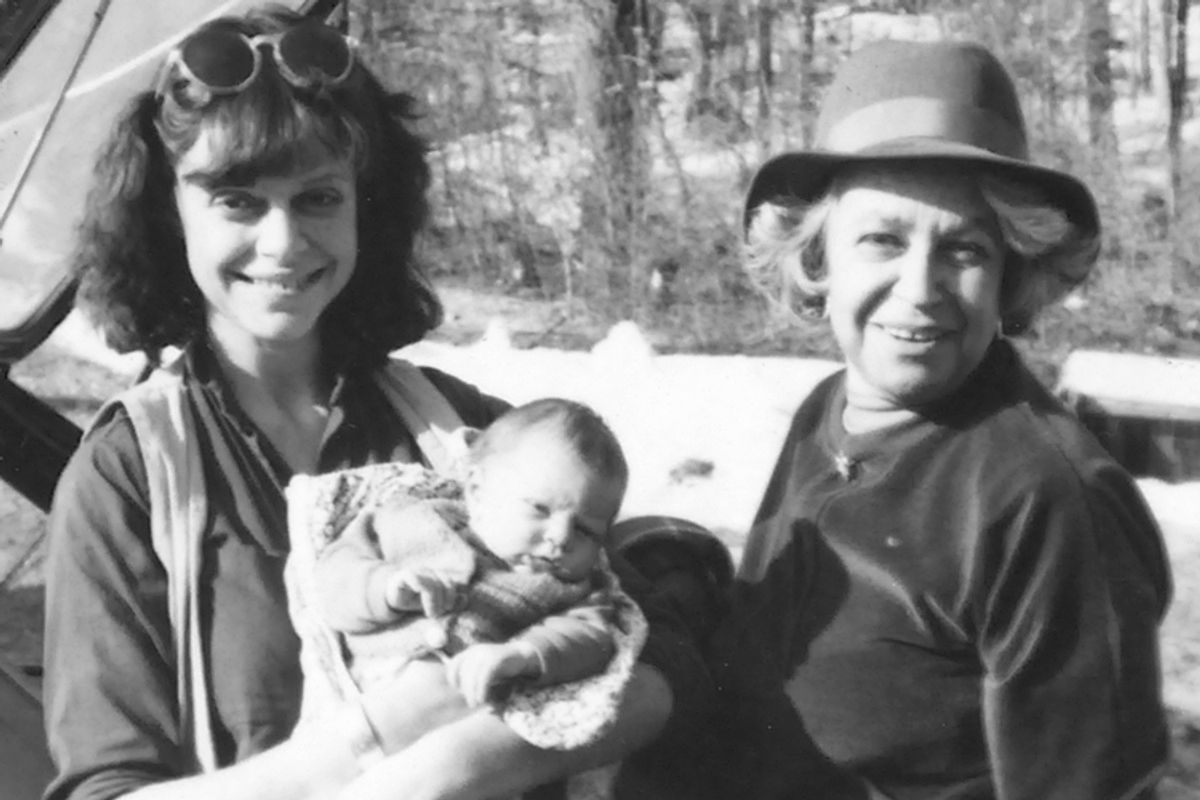

Our mother belonged to that generation of women for whom child-raising and homemaking stood, so often, as the sole occupation — the only one available, and given the alternatives, very likely the most rewarding. Though she possessed a powerful intellect and a Radcliffe Ph.D., my mother struggled, throughout my childhood in the 1950s and '60s, in the unsuccessful pursuit of a full-time teaching position, or any other employment a man with her credentials would easily have secured. For the years I lived at home — until she reached her late 40s — my mother sold encyclopedias door-to-door, found part-time work at a local high school, and ghost-wrote columns for a magazine psychologist who paid her a couple of hundred dollars a month for the job.

It was not so surprising, then, that for all of those years, my mother made the raising of her children her central pursuit, and that as she neared death — and despite having eventually, later in life, created a career for herself — it would be her children’s successes that would stand, for her, as the most compelling testament to her life’s meaning and value.

Much has changed for mothers of my generation, and those after me. But in one way, at least, the notion lingers that where a man — a father — may screw up mightily in his personal life, and still be viewed as a successful individual, for a woman who has children, whatever else she may achieve in life, the measure of success or failure continues to rest to a significant degree on how well those offspring turn out. Who hasn’t heard that quotation from Jacqueline Kennedy on the subject: “If you bungle raising your children, I don’t think whatever else you do matters much.”

Unlike my mother, I was able to carve out a career as a young woman, and maintain it throughout the years of raising my three children, but I used to subscribe to this kind of thinking, too. When a child visited our house, who seemed spoiled or out of control, or socially inept, I’d find myself quietly passing judgment on the parents. The mother in particular. On the other side of things: I derived a lot of pleasure out of my own children’s friendly, well-adjusted way of presenting themselves in the world. In meetings with editors or reunions with high school classmates, I loved showing pictures of the three of them. I passed these pictures around, as if presenting my credentials. I did this. I made these people. I’m responsible for those happy faces.

I didn’t take sole credit, but if — during the years my children remained at home, and plenty of years after that — you had asked me from what source I took my greatest sense of pride, it would not have been the books I wrote that headed the list, or the political campaigns in which I’d been active, the friendships I’d maintained. I would have said (or thought, at least): I raised great children.

And in fact, I might have written a half-dozen more books, and done plenty more besides, if I hadn’t expended so much energy on that aspect of life. I was one of those mothers who sought to provide — in a way that could certainly be termed obsessive — every kind of stimulating, enriching experience within my resources, and beyond them. Whatever our finances, my children never did without art supplies or music lessons or visits to museums. If the best school was located 25 miles from our house, I’d shovel snow off the car at dawn every morning in winter, to drive them there. When the divorce split us up, I made sure we got therapy. When college time came, I refinanced our house to pay for it.

If I were asked to provide a single image of the kind of over-the-top self-sacrifice of which I was capable, over those years (though there would be lots to choose from), it’s this one:

The four of us have traveled to London — one of many trips undertaken, despite shaky finances, out of a belief in the importance of what I used to call “expanding their horizons.” My 12-year-old son, Charlie, has chosen, for his souvenir of the trip, a set of leather juggling balls. As we enter the Piccadilly Square tube station, he’s tossing them in midair. One falls into the pit where the trains come. He gasps. I jump down in the pit to retrieve it.

Over the years since, all of us survived plenty. As a mother, I lived through a couple of devastating and humbling failures that taught me never to judge another parent until I’ve walked in her shoes. My children are grown and gone from home now. The years are far behind in which I believed I could control their universe, or spare them the kind of pain life invariably provides, even for those with the most attentive and over-functioning of mothers. (In fact, it may be those very mothers who become the source of pain.)

Mother’s Day, 2014: Despite all the trouble their parents and the rest of life has offered up over the years, my children have all grown into healthy, productive adults doing interesting and worthwhile things with their lives. And of course, it is a source of huge happiness for me that this is true. I adore them all.

But I also know a humbling fact, from watching the lives of my fellow mothers (fathers too, but mothers have it worse), and from many years of teaching classes in memoir, and hearing stories of other people’s lives, women’s stories in particular. In every class I’ve ever taught, I meet at least one woman (but generally two or three) tormented by guilt over how messed up her children’s lives have become, and how it’s all her fault.

The list is long, of good and loving mothers I know — of now-adult children, the ages of mine— who are not doing so well. Some of these mothers may truly have “bungled” how they raised their children. But I can name plenty of others who breast-fed their children, served them good meals, stayed home when they were sick (or every day), read to them, sang to them, taught them to ride their bikes and swim and ski, and above all, nurtured them daily (in families that remained — unlike my own — “intact”).

And their children are in drug rehab. Or they’re in jail, or suffering from profound depression. I know more than one mother — the kind of person who up until that moment would have been described as “a good mother” by anyone who knew her — whose child committed suicide.

What does this say about those mothers? If the value of these women’s lives were measured by the success of their children, they have failed, and, by the Jacqueline Kennedy measure at least, nothing else they may have succeeded at should matter all that much, as a result. In the eyes of many people (including the woman herself), a woman whose children fail to measure up is guilty of an even greater failure. Bad mothering.

As much as I believe in the importance, for those who choose to become parents, of devoting one’s best energy to the task, I also know now that so much of the story of a young person’s trajectory in the world has to do with things no parent can control: A patch of ice on the road that causes a car to spin into oncoming traffic. A school bully who sends a hate-filled text to a vulnerable 14-year-old. The simple and terrible shift of body chemistry that sometimes, inexplicably, produces a psychotic break in a young person who was, up until then, a high-functioning college student.

When I was a young mother myself — and I actually thought I could spare my children pain by rescuing a juggling ball, or ensure their happiness by providing a terrific drum set or a tennis racquet or tuition at a great school — I believed I could control my children’s world. Because there was a time, of course, when virtually every aspect of their lives did in fact depend on me. It ended the day they made their exit from my uterus. And from that moment on, my power over their lives — the degree to which I can take credit for their successes or blame for their failures — has been steadily diminishing.

My children are all in their 30s now — my daughter the age I was when my mother, her grandmother, named me one of her two greatest accomplishments. As for me: I would say I’m proud of my children, except that unlike my own mother, I see them as having created for themselves a significant portion of the lives they’ve made. I set certain options out for them (along with, no doubt, no shortage of traumas and losses. My divorce from their father top of the list).

But what I believe now is that our sons and daughters decide for themselves what they will do with the gifts their parents lay before them, as well as the damage. We instruct, advise, comfort, encourage, caution and model. We offer up our never-ending love. But in the end, it is for every child to create her own path — with health, luck and even body chemistry all playing a part.

This knowledge both humbles and frees me. I am not my mother’s “accomplishment.” The three children I gave birth to are not mine.

Shares