Imagine you’re a conservative state politician ideologically opposed to government-provided health insurance for those with low incomes, but you nonetheless recognize the folly in forgoing billions of dollars in federal funds available to states that expand Medicaid simply to prove a Dickensian point (of questionable popularity).

It turns out that you can take the money, expand but also partially privatize Medicaid in your state, scrap some of its benefits, funnel a piece of the cash to the insurance industry, create new co-payments to make life a bit harder for those who happen to be both sick and broke, and even teach the poor a lesson or two about the value of health, wealth and weight loss, to boot!

In a concerning new trend, states around the country are pursuing a so-called private option to the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion, changing it to a system of “premium support” inclusive of various conservative “innovative solutions.” Other states, meanwhile, are maintaining traditional Medicaid but adding unprecedented forms of cost sharing. In doing so, even as they begrudgingly accept Medicaid’s expansion, these states – largely under the control of Republican governors, legislatures or both – are historically reshaping the program. The price of their “innovation” will – predictably – be paid by those living in (or near) poverty.

First, how did this “private option” emerge? The ACA was written to expand Medicaid to everyone in the country earning less than 138 percent of the federal poverty level. This expansion is fully funded by the federal government until 2016, after which its contribution decreases (though to no less than 90 percent). However, in June 2012 the Supreme Court ruled that though the individual mandate was constitutional, the federal government couldn’t require states to expand their Medicaid programs; ever since, the Medicaid expansion has been hotly contested in state after state. Though 26 states have so far chosen to expand healthcare for low-income adults, the remaining 24 (mostly red) states have refused (or are still debating) the expansion.

But apart from the states that have flatly rejected the Medicaid expansion (which would have happened almost entirely on the federal government’s dime), many other states are using their newfound leverage to take the money and run (in a conservative direction). And the administration – eager to maximize the scope of the expansion – has been willing to compromise.

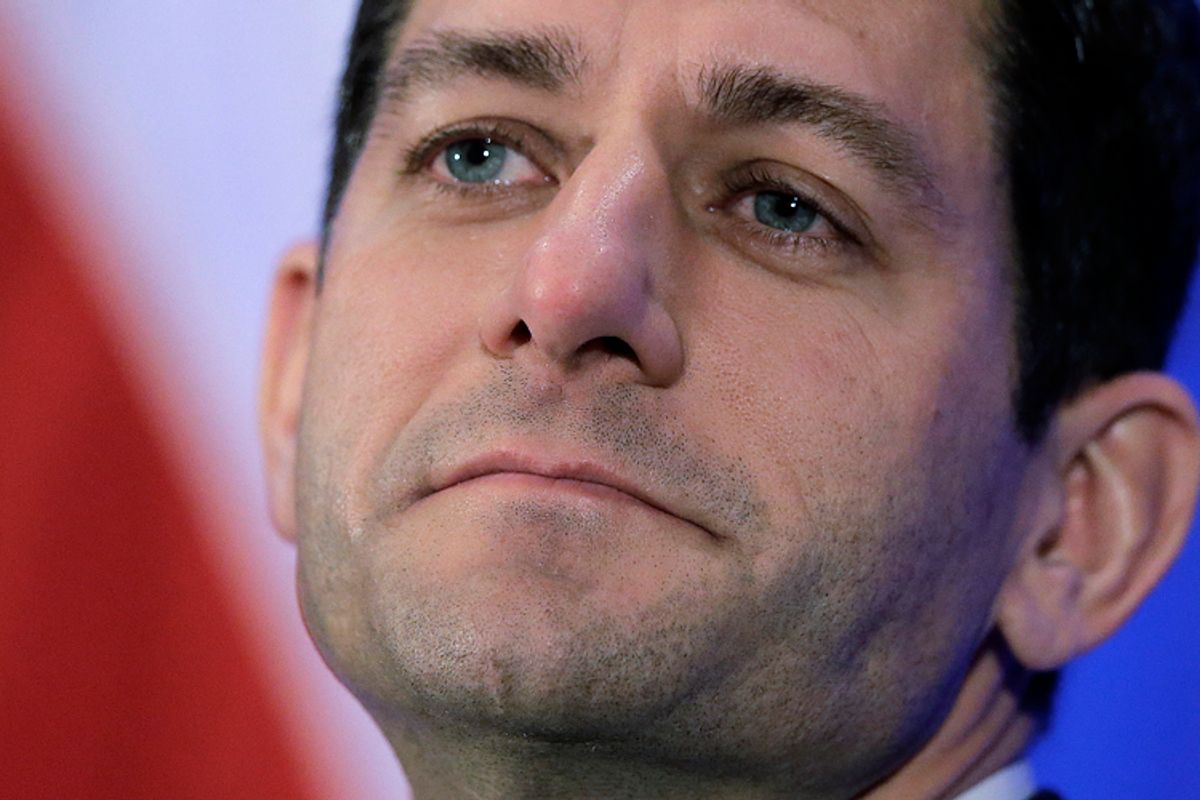

Arkansas was the first state to win a federal waiver to create a “private option” as a “compromise” to the Medicaid expansion. Rather than enroll the newly eligible into the traditional Medicaid program, Arkansas will instead use federal money to help those with low income buy private health plans, analogous to the concept of “premium support” that Paul Ryan is perpetually pushing for Medicare. More recently, in December, Iowa became the second state to win a private option waiver from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Many other states – ranging from Pennsylvania to New Hampshire to Utah – are seeking to follow suit.

Now, private health insurance has consistently been found to be more expensive than public programs, so it’s clear that a consideration for costs has little to do with this strategy. The specifics of the waivers, however, which strip benefits and raise co-pays, more clearly elucidate the purpose of the private option.

Take Iowa, which used its waiver to exclude coverage of some traditional Medicaid benefits, like nonemergency medical transportation (at least for one year, after which CMS has required that it study the results). Now it might not seem obvious why a health insurance program should cover such transportation (most don’t), unless we appreciate the minimal resources and frequently complex medical needs of many of those who rely on Medicaid.

It’s simply unrealistic for individuals who have minimal or no disposable income, who may have multiple chronic illnesses or mental health problems, to coordinate and fund transportation to their innumerable treatments, tests, office visits, outpatient procedures, and so forth. According to a recent survey, for instance, of those using Medicaid-funded transportation, almost a third were attending behavioral health or substance abuse treatment, while another 18 percent needed it to make it to dialysis. In fact, in the case Smith v. Vowell, a federal court went so far as to find that Texas’ “deprivation of medically necessary transportation” to patients receiving public healthcare benefits was neither “therapeutic, practical, nor legal.” The Iowa state government nonetheless felt the need to take a brave stand against this important program (even though it would’ve paid nothing for it upfront, and a small fraction indefinitely in the future).

What else is “innovative” about private option Medicaid? One commonality among the proposals is the introduction of new co-payments for Medicaid enrollees, for such things like office visits and prescriptions. In the case of Iowa and Arkansas, these co-payments can amount to 5 percent of annual income. The sicker you are, of course, the more you’ll need to spend, which apparently – for some lawmakers – makes perfect sense. Iowa, Pennsylvania and Michigan are also enthused about charging for “nonemergency” use of the emergency room, which amounts to a $50 fee in the case of Michigan.

Now, presumably, the point of such fees is to punish those hypothetical individuals who, for unclear reasons, purposefully scam Medicaid by wasting days at a time sitting in E.R.s, despite knowing that they are perfectly well and sound. Could there be a flaw in such reasoning, however? After all, I (like most physicians) have sent patients to the E.R. for what sounded like concerning symptoms over the phone (or even from clinic), who ultimately didn’t require admission to the hospital. Clearly, physicians can’t perfectly predict who actually “needs” the E.R., though apparently our patients with low income must quickly learn how to – or otherwise pay a price (or, even worse, avoid the E.R. altogether, even when they might actually need it).

Now such “cost sharing” represents “largely uncharted territory” for Medicaid, as an article in the New England Journal of Medicine recently put it – and for a good reason. For though these fees and co-payments may be pocket change to the well-paid legislators who created them (many of whom will later leverage their purported “public service” into lucrative careers in lobbying or industry), for those living in poverty, these quantities of money mean a great deal. At the very least, such co-payments create a strong disincentive to use healthcare, to fill prescriptions, to see their doctor, or even to sign up for Medicaid to begin with.

However, perhaps even more obnoxious – if not quite as deleterious – are the so-called Wellness Programs that the private option programs create. For instance, the “Iowa Health and Wellness Plan” not only creates co-payments at point of use, but also charges enrollees a monthly premium, which they can offset by earning “rewards” through engaging in “healthy behaviors.” “In the new plans,” a recent white paper from the Iowa state government proclaims, “members have a financial stake in their healthcare. The waivers are designed to drive appropriate consumer behavior in their use of the health care system.”

It’s obviously not enough that the chronically ill living below or near the poverty level have their lives on the line: We must teach them to be better healthcare consumers. But how can we drive such individuals (who apparently care nothing for health for health’s sake) toward “appropriate consumer behavior”? Well, it’s complicated. According to the white paper, enrollees should work to earn “rewards” to offset their monthly premiums by completing various health-related tasks. These rewards may either be “basic” or “enhanced,” depending on the “level or milestone achieved.”

For instance, “accomplishing a weight loss of 5 percent may result in an ‘enhanced’ reward of an additional $50.” This $50 can then be used to pay down the premium that private option Medicaid itself created. I should point out that there is no support for such programs in the medical literature; a review in the health policy journal Health Affairs last year concluded that “evidence is sparse that financial incentives induce behavior that improves health,” whether with respect to losing weight or quitting smoking. Even putting aside the empiric evidence, however, it’s surprising that anyone would even think otherwise: nicotine is so addictive that it can surmount the concerns of entirely reasonable and intelligent people about lung cancer, emphysema, stroke, heart attacks, and death. Does anyone really think that a $25 gift card will be a game changer? In any event (as most of us among the imperfect can attest), it’s quite hard to quit unhealthy habits or lose weight, even when one is financially secure; under severe financial, physical or psychological stress or strain, it’s that much harder. Imposing a fee and then requiring various behavioral changes (say, weight loss) to offset this fee is not all that different than directly penalizing those with low income for, say, being overweight. That may bring a smile to the face of some; I find it petty and unproductive.

In other words, between privatization, co-pays, cutbacks in important benefits, and these silly “wellness” programs, the private option somehow manages to combine the worst aspects of “liberal” public health paternalism, neoliberal healthcare consumerism, and conservative anti-welfarism. What’s not to like?

In sum, the waivers already won have allowed federal Medicaid dollars to flow into private insurance companies; have initiated the rollback of traditional Medicaid services like medical transportation; have facilitated the introduction of co-payments and premiums for people who have almost no money; and have introduced repugnant “wellness programs” that allegedly “drive appropriate consumer behavior” toward health. But these programs might even have a moral purpose! Pennsylvania, for instance, is reportedly working not only to eliminate coverage for transportation, but also to waive the requirement that it pay for contraceptives and the implantation of intrauterine devices for Medicaid patients. While the administration will hopefully have the good sense to send such nonsense back to the Keystone State, I believe they’ve already conceded too much.

“Programs for poor people,” goes an old aphorism, “are poor programs.” With respect to a means-tested program such as Medicaid, there is no doubt truth in this. As compared to Medicare or private insurance, patients with Medicaid can face serious hurdles in accessing the healthcare system, whatever their benefits on paper. Of course, to address such a disparity, we would need a universal single-payer healthcare system for all. Before we achieve that, however, Medicaid is what those with low-incomes rely on. The refusal of half the states in the country to expand Medicaid could cause, at least by one estimate, in excess of 7,000 deaths. Meanwhile, as I’ve explored here, other states are seeking to convert the public Medicaid program into a system of premium support bereft of important benefits and full of new charges and paternalistic “rewards.”

Those with low incomes (and, in point of fact, most of those with middle incomes as well) have been essentially excluded from benefiting from the last three decades of economic growth, while a tiny sliver of the country has prospered enormously. Providing adequate health insurance, without co-payments and with important benefits like transportation, is the least that they deserve. Now some might say that whatever the problems with the private option, some healthcare is better than none. That may very well be true, but it doesn’t mean taking it with a smile – or without a fight.

Shares