Common wisdom says that Elvis's adoption of black sources, and in particular his cover of Arthur Crudup's R&B hit "That's All Right" in 1954, was an apocalyptic break with country tradition. Elvis, then, invented rock and roll by integrating American music. The only problem with this version of history is that it's not true. Elvis wasn't the first rural white performer to work in a black musical idiom by a long shot, as the list below demonstrates.

Allen Brothers, "Salty Dog Blues" 1926

Country musicians were covering African-American songs long before R&B existed. The Allen Brothers recorded this version of blues performer Papa Charlie Jackson's "Salty Dog Blues" in 1926. In fact, it's somewhat misleading to categorize the Allen Brothers as "country" and Jackson as "blues," given their similar styles and repertoire. Some Allen Brothers recordings were famously released by their record company in its race series instead of its hillbilly series, much to the brothers' dismay. The performers wanted to keep their marketing segregated out of racism, but as far as musical style went, there simply wasn't that much difference between black and white.

Maddox Brothers and Rose, "Milk Cow Blues" 1947

The Maddox Brothers cover of Kokomo Arnold's 1934 blues hit "Milk Cow Blues" is a number that has made its way firmly into the country repertoire; there are also versions by Bob Wills and, in the modern era, George Strait. The Maddox Brothers continued to cover black artists, most notably with a great 1955 performance of Ruth Brown's "Wild, Wild Young Men." That song was no doubt inspired in part by Elvis's success, but, again, it was also simply a reflection of the fact that the Maddox Brothers had long been influenced by blues, jump blues, and African-American styles.

Mustard and Gravy, "Be Bop Boogie" 1950

This isn't an R&B cover by Mustard and Gravy (Frank Rice and Ernest W. Stokes), but it certainly, and deliberately, references the R&B tradition. Be Bop was well-known as a jazz style by 1950, but it had also become associated with rhythm and blues in songs like Lionel Hampton's 1946 hit "Hey-Ba-Ba-Re-Bop." The trombone solo makes the link to horn-driven black bands explicit — though the use of saxophones, trumpets and horns was far from uncommon in country at the time.

Moon Mullican, "Well Oh Well" 1950

The King label was a hotbed of musical integration, in large part because of producer Henry Glover, an African-American producer who oversaw both King's country and R&B divisions. Glover would often have white performers cover numbers from the R&B catalog, like "Well Oh Well," which was initially a hit for Tiny Bradshaw. Glover was especially close friends with Moon Mullican, who always acknowledged the black influence on his boogie-woogie piano style, and who often played with black performers in live settings. The session for "Well Oh Well" was integrated as well; Eagle Eye Shields was the drummer, and Clarence Mack played bass, as he had on the Bradshaw session. In an interview later in life, Glover said, "Moon had such a great soul. He was just like a black man to me, you know, like he thought, felt and expressed himself and everything else."

Wynonie Harris, "Don't Roll Those Bloodshot Eyes at Me" 1951

Glover not only gave R&B tunes to his country artists; he also had R&B performers cover country tunes. This song was written by Western swing performer Hank Penny, complete with sax solo. Harris's version doesn't so much transform the song as it uncovers its jive-talking R&B heart.

Hank Penny, "Catch 'Em Young, Treat 'Em Rough, Tell 'Em Nothin" 1951

The earthy, not-politically-correct sex war advice here is quintessential Hank Penny; I'd always assumed he'd written this. And he may have. But it's also possible that it was originally by Mabel Scott. I haven't been able to track down enough information to know for sure who did the original. If you know who was covering whom, please let me know in comments.

Hardrock Gunter and Roberta Lee, "Sixty Minute Man" 1951

"Sixty Minute Man" was a major pop crossover hit for Billy Ward and the Dominoes in 1951. As such, it inevitably generated covers, such as this country version. As this demonstrates, Elvis didn't make R&B successful with white audiences; rather, his decision to cover black artists had to have been influenced (like Gunter and Lee's) by the fact that such artists were already enjoying great popularity with a wide range of listeners.

Zeb Turner, "I Got Loaded"

Peppermint Harris's original 1951 single has a shoulder-shrugging honky-tonk feel that just about calls for a country cover. I'm not sure of the exact date on Turner's version, but these things tended to be rushed to market, so it must have been in '51 or '52.

Billy Jack Wills, "I Don't Know" 1952[?]

Billy Jack Wills is less well-known and successful than Bob Wills, but his band was in many ways as innovative as his brother's. Where Bob's music was based in jazz swing and blues, Billy Jack embraced bop and R&B, as on this spirited cover of Willie Mabon's "I Don't Know," with strutting trumpet and mandolinist Tiny Moore taking a turn on vocals.

Leon McAuliffe, "Night Train" 1952[?]

McAuliffe was most famous for his work in Bob Wills' band. He then formed his own outfit, and while he wasn't in general as progressive as Billy Jack, he too flirted with R&B, as this cover of Jimmy Forrest's Night Train demonstrates — with the squonking gut-bucket sax replaced by McAuliffe's surprisingly gut-bucket steel guitar. You wouldn't think he could make it do that. (Though they've got a sax in the band too, just in case.)

Jack Turner and His Granger County Gang, "Hound Dog" c.1953

"Jack Turner" is a pseudonym for virtuoso country novelty duo Homer & Jethro, covering (complete with barking) the Leiber & Stoller novelty blues hit originally recorded by Big Mama Thornton. Again, Elvis's 1956 cover version wasn't an innovation, but rather one in a series of white performers who performed the song.

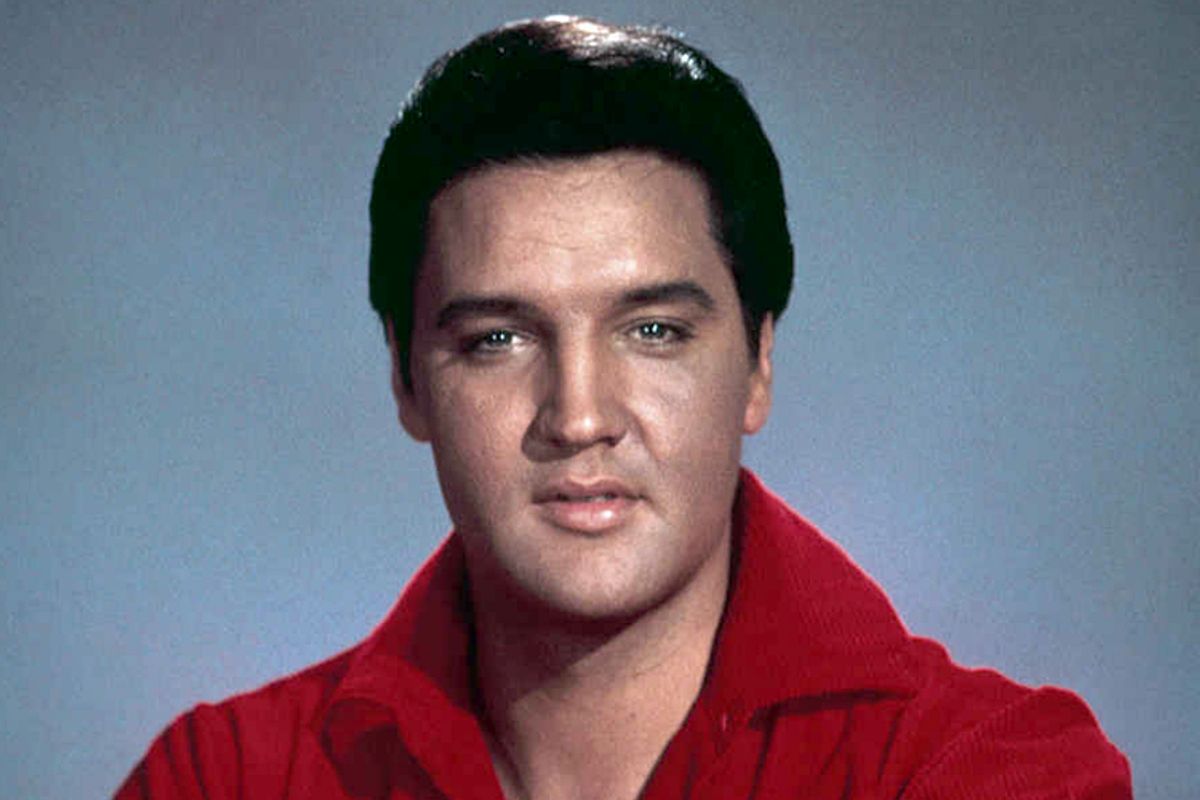

Elvis Presley, "That's All Right" 1954

Putting Elvis in context can be seen as diminishing him in some ways. While he was a great performer, his was not the first white man to get a black sound, as Sam Phillips suggested — white performers had been covering R&B for years, and blues for decades, before Elvis had his breakthrough.

The fact that Elvis's choice of cover material wasn't anything special also rebuts some criticisms of him, though. Elvis didn't steal black music; on the contrary, white performers had been covering black music since the dawn of recording technology, and vice versa. In fact, as the Allen Brothers demonstrate, separating black and white music had as much to do with segregated marketing as with any essential differences in performance styles. "That's All Right" is perhaps best seen not as a founding moment for white people discovering black music, but rather as an especially popular entry in a long American musical tradition of integration.

Shares