Give me a book that begins with a time and a date and a boring address, something along the lines of “At 9:36 on March 24, 1982, Dep. Frank McGruff of the Huntington County Sheriff’s Department was dispatched to 234 Maple Street in Pleasantville, North Carolina, a quiet, suburb 10 miles west of Raleigh, to follow up on reports of gunshots and screams.”

There is nothing more generic than this sort of sentence — which is why I was easily able to make one up on the fly — and yet there’s nothing more seductive, either. In it is promised: the regular-guy lawman (who always seems to have a new baby at home), the horrific crime scene (there is always more blood than anyone expects), the enigmatic object found lying in the foyer (marked with an X in the helpfully provided floor plan), the minute-by-minute timeline of that fatal half-hour, the witness reports that don’t add up, the fractal-like multiplication of scenarios and theories and complications.

I’ve always felt somewhat sheepish about my appetite for true crime narratives, associated as they are with fat, flimsy paperbacks scavenged from the 25-cent box at garage sales, their battered covers branded with screaming two-word titles stamped in silver foil, blood dripping luridly from the last letter. The most famous practitioners of this louche genre — Joe McGinniss, Ann Rule, Vincent Bugliosi — come coated with a thin, greasy film of dubious repute and poor taste. (Can there ever be a valid reason to title a book “A Rose for Her Grave”?) True crime is also the mother’s milk of risible tabloid journalism, of endless trashy news cycles in which the same photo of a wide-eyed innocent bride (where is she?); a gap-toothed kindergarten student (who killed him?); a bleary-eyed, stubbled suspect (why did he do it?) appear over and over and over again.

Occasionally, true crime is where literary writers go to slum and, not coincidentally, make some real money: Truman Capote’s “In Cold Blood,” Norman Mailer’s “The Executioner’s Song.” It’s not the Great American Novel, yet somehow such books have a tendency to end up the most admired works of a celebrated author’s career. Is it because better writers tease something out of the genre that pulp peddlers can’t, or is it just that their blue-chip names give readers a free pass to indulge a guilty pleasure?

By contrast, crime fiction has a better rep. It is the most respectable form of genre fiction, the one that even the snootiest literary critics will admit to enjoying now and then. They justly praise the innovative prose styles of Raymond Chandler or Elmore Leonard as vehicles for a distinctively American voice. And crime — transgression of the social and moral order — is one of literature’s central themes, after all. Isn’t one of the greatest novels of all time called “Crime and Punishment”? Plus, from Cormac McCarthy’s “No Country for Old Men” to Toni Morrison’s “Beloved,” many novels by literary titans are crime fiction by another name.

True crime, however, labors always under the stigma of voyeurism, or worse. It’s not just unseemly to linger over the bloodied bodies of the dead and the hideous sufferings inflicted upon them in their final hours, it’s also kind of sick. Gillian Flynn’s second novel, “Dark Places,” describes the wincing interactions between its narrator — survivor of a notorious multiple murder like the Clutter killings of “In Cold Blood” — and a creepy subculture of murder “fans” and collectors; when she’s hard up for cash, she’s forced to auction off family memorabilia at their conventions. Yuck.

The very thing that makes true crime compelling — this really happened — also makes it distasteful: the use of human agony for the purposes of entertainment. Of course, what is the novel if not a voyeuristic enterprise, an attempt to glimpse inside the minds and hearts of other people? But with fiction, no actual people are exploited in the making.

I love crime fiction, too, but lately I’ve come to appreciate true crime more, specifically for its lack of certain features that crime fiction nearly always supplies: solutions, explanations, answers. Even if the culprit isn’t always caught and brought to justice in a detective novel, we expect to find out whodunit, and that expectation had better be satisfied. A novelist who dares to build her narrative around a murder and then refuses to collar the perp by the last chapter — as Donna Tartt did in her sumptuous, underappreciated second novel, “The Little Friend” — will never hear the end of it. Readers of books and viewers of television and film demand not only to know who did it but why, preferably with a tidy little back story about a molesting uncle, bullying schoolmates or a mom who tricked with sailors in the next room. We believe in evil, but we also want pop psychology to explain it away.

Crime fiction reassures us that for every murder there is a sleuth as obsessed as we are with getting to the bottom of the puzzle. There are the formulaic clashes between the committed police detective and the self-serving brass, the feds who interfere with the locals (or vice versa) for purely territorial reasons, the nagging spouse and the occasional sloppy, time-serving colleague who just wants to wrap this thing up before he’s set to retire with a full pension. But there’s also always someone, the hero — whether public officer or private dick — who really, really wants to find out the truth and has the brains (and sometimes the brawn) required to do it.

Because most of us have a lot more experience with crime fiction — TV and movies, but also books — than we do with actual crime, our sense of how law enforcement works has been distorted by the imperatives of entertainment. Forensic scientists often complain that the public expects them to possess and deploy the wizardly high-tech tools they see every week on “CSI.” Because the “CSI” team’s gear is presented as omniscient and infallible, legal professionals must contend with jurors’ overinflated confidence in forensic evidence. Even the most appalling news stories of incompetent or corrupt lab workers will never register as deeply as watching Gil Grissom and his earnest sidekicks stay up all night and ruin their marriages for the sake of seeing justice done.

For all their lingering shots of mangled bodies and gooey, maggot-ridden corpses, these TV procedurals paint a too-pretty picture. If Jack Nicholson were a true-crime author, he’d be telling the audience for such pseudo-gritty shows that they can’t handle the truth. Finding myself seated next to a criminal prosecutor-turned-defense attorney at a wedding several years ago, I asked him what pop culture gets the most wrong about crime and punishment in America. After a long pause, he said, “I’m torn between two answers: How much police care about getting it right and how competent they are to do it.”

True crime is not above trafficking in misleading clichés — because, let’s face it, there’s not much that true crime is above. The majority of the genre is cheap sensationalism, deploying the most shopworn clichés: tragic maidens; idyllic small towns; smiling devils; winsome, doomed tots. Much true crime has achieved its goals if it gives its readers something to shiver over late at night or to whisper about at school. (Most of my early knowledge of true crime classics like “Helter Skelter” came from other girls who got ahold of the books while baby sitting and recounted the most horrific details to a breathless audience on the playground the next day.) Plenty of it offers a comforting message similar to that of crime fiction: that, for all the bewildering and seemingly random violence of this world, it is usually possible for us to know what really happened and who’s responsible.

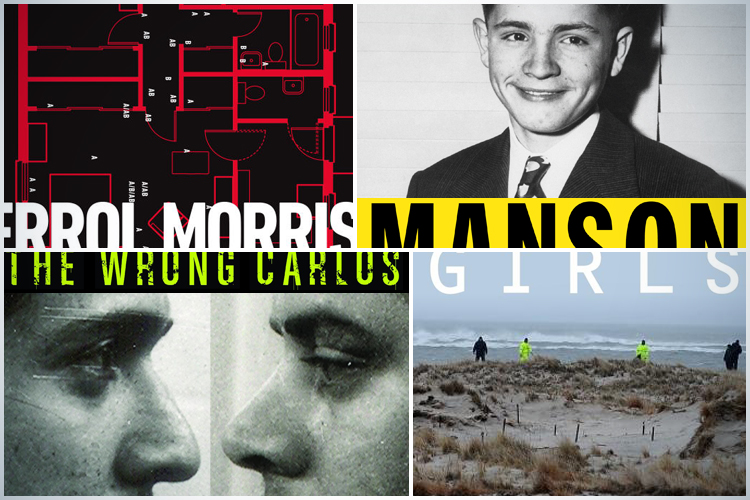

But we also live in a golden age when it comes to a more challenging vein of true crime. These books include Robert Kolker’s “Lost Girls,” about 14 unsolved murders in Long Island; Raymond Bonner’s “Anatomy of Injustice,” about the wrongful capital conviction of a black handyman for the rape and murder of an elderly white widow in South Carolina; Janet Malcolm’s “Iphigenia in Forest Hills,” about the celebrated journalist’s inability to accept the guilty verdict against a young mother accused of hiring a man to murder her ex-husband; and Errol Morris’ “A Wilderness of Error,” which is in part a challenge to another milestone in the genre, Joe McGinniss’ “Fatal Vision.” Coming up next month is another landmark, “The Wrong Carlos,” by James Liebman and the Columbia DeLuna Project, an exhaustively researched consideration of a 1980s case in which the state of Texas most likely executed the wrong man.

Even true crime books in which the identity of the killer is uncontested can open up welcome vistas of uncertainty. Recently, Anand Giridharadas’ “The True American” examines the lives of two men: the sole survivor of a hate-crime spree, who forgave and tried to save his would-be killer, and the killer himself, who seems to have become a different man before his 2011 execution; who was he, really? Dave Cullen’s masterful “Columbine,” published in 2009, offers the most definitive account of the infamous school shooting and clears up many misperceptions, but still leaves the reader with a sense that the reasons for such acts may be fundamentally unknowable. Several years ago, when I was interviewing Margaret Atwood about “Alias Grace,” her novel about a maid convicted of killing her master in 19th-century Canada, she remarked that murderers themselves often don’t seem to understand their own crimes. They describe the acts as something that “just happened” or as if they were committed by someone else even as they acknowledge they did it. The true crime accounts I’ve read confirm what Atwood said.

Most important of all, true crime reminds its readers over and over again that most detectives aren’t fantastically clever, that most investigations make dozens of significant mistakes and that even the most seemingly hard evidence can become as indeterminate as a quantum particle under sustained study. Sometimes the confusion is understandable. Jeff Guinn’s “Manson,” a biography of the murderous cult leader published last year, recounts how long the LAPD spent pursuing a bogus scenario in investigating the massacre at Sharon Tate’s home.

Investigators assumed that because drugs were found on the premises, the motive was probably a drug deal or connection gone bad. Manson had his followers plant “clues,” in the form of weird words written on the wall in blood, with the bizarre idea that the police would instantly link these words to the Black Panthers. (They instead assumed it was just crazy druggie writing, which of course it was.) Much time was lost before the cops were put on the right track by an informant. This, incidentally, is how most real-life whodunits, such as the Unabomber attacks, seem to be solved. There’s nothing like true crime to dispel the notion that criminals get caught because of a detective’s brilliant reading of the clues. Rather, they get caught because someone rats them out.

Nowhere is the danger of investigators’ tendency to settle too early on a theory of the crime more evident than in stories of wrongful conviction. As “Anatomy of Injustice” tells it, police decided that Edward Lee Elmore, the simple-minded African-American man who had mowed neighborhood lawns for years, suddenly turned violent. Under the influence of a suspiciously meddlesome neighbor, a local city councilman, they ignored significant evidence contradicting this theory, and eventually resorted to falsifying evidence, while Elmore’s own lawyers barely bothered to defend him at all. Finally, thanks to the efforts of an attorney working for South Carolina’s Center for Capital Litigation, the conviction was overturned. The actual murderer has never been identified, but at least an innocent man has escaped death row.

Investigations aren’t always led astray by deliberate manipulation, however. In “The Wrong Carlos,” confused and inept handling of the crime scene, witnesses and hunt for the man who stabbed a convenience store clerk in Corpus Christi combined with coincidence and bad luck to lead to the unjust execution of Carlos DeLuna. He was the spitting image of the likely culprit to the degree that even people who knew either of the men quite well couldn’t tell photos of them apart. Under the aegis of Liebman, 12 Columbia Law School students pored over the records of the case, producing a meticulous and highly detailed report on the crime investigation and trial — which, while sobering, is also catnip for the amateur detective. It strongly suggests DeLuna was innocent and it’s so convincing that even the victim’s brother agrees.

Robert Kolker’s “Lost Girls” and Errol Morris’ “A Wilderness of Error” may be the most accomplished true crime narratives I’ve read in recent years. The killer or killers responsible for dumping bodies along a lonely Long Island road have yet to be identified. The investigation appears to be stalled for a variety of reasons having to do with the personalities and ambitions of local officials. So Kolker’s “Lost Girls” focuses instead on the lives and families of the dead, young women who drifted into the world of prostitution and could not succeed at pulling themselves out again. It’s a portrait of underclass life, frayed by substance abuse, domestic violence, crime and fecklessness, and it asks not what circumstances create a monster but which ones forge his victims.

“A Wilderness of Error” is remarkable not just for questioning a murder investigation and conviction but also for condemning the famous true-crime narrative written about them. Morris is a master of the genre, albeit in a different medium (documentary film) and can even claim to have gotten an innocent man out of jail by making “The Thin Blue Line” in 1988. Above all, he is preoccupied with how we establish what’s true. His first book, “Believing Is Seeing: Observations on the Mysteries of Photography,” dismantles our faith in the facticity of photographed images. “A Wilderness of Error,” his second, concerns the case of Jeffrey MacDonald, convicted of murdering his wife and two small children in 1970. The crimes were the center of a bestselling book, “Fatal Vision” by Joe McGinniss, later made into a TV movie, that pressed home McGinniss’ theory that MacDonald was a psychopath.

The writing of “Fatal Vision” was the subject of yet another book, Janet Malcolm’s “The Journalist and the Murderer,” devoted to probing the moral soft spots in all journalists’ relationships to their subjects, but Morris believes these murders were insufficiently investigated and that MacDonald did not get a fair trial. Many aficionados of the trial find Morris’ arguments unconvincing, but that is partly Morris’ point. Just like the cops, outside observers settle on a story about what happened and become invested in it. They then ignore or dismiss any evidence that undermines that story, often with a vehemence that increases as the counter-evidence mounts. Certainty, an emotional state all too common today, is less a testament to the merits of a belief than a measure of how much we want to go on believing it.

At the very least, Morris presents a convincing case that an uncertain McGinniss was pushed into endorsing MacDonald’s guilt by his publisher because offering a conclusion would make for a more satisfying book. Later, of course, the author had no choice but to double down on that conclusion, and whether or not he believed it before his editor urged him to declare the case solved in his own mind, he seems to have fully believed it in the end. All this would be meat for an interesting consideration of the nature of truth and whether it can ever be meaningfully detached from desire, but as Morris keeps pointing out, when it comes to true crime, real lives and real justice are at stake. Crime fiction can afford to go on telling us what we want to hear, but at its best true crime insists on telling us what we can’t afford to forget.