Of course Republicans are going to compare the prisoner swap that won the release of Army Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl to Benghazi. They both start with B. It leads to their favorite words that start with I: investigation, and possibly impeachment.

The ridiculous Andrew McCarthy, flacking his new book making the case for Obama’s impeachment, of course finds more fodder in the prisoner transfer. Tuesday morning he was joined by Fox News “legal analyst” Andrew Napolitano and a man who couldn't even hold on to a congressional seat for a second term, Allen West. The shift to Bergdahl reflects growing concern that the right’s Benghazi dishonesty isn’t working with voters. Even conservative analysts have chided colleagues for Benghazi overreach. Sure, Trey Gowdy will continue with his election year partisan witch hunt, but the right is wagering the Bergdahl story might hurt Obama more.

The anti-Bergdahl hysteria plays into six years of scurrilous insinuation that Obama is a secret Muslim who either supports or sympathizes with our enemies. Even "moderate" Mitt Romney, you’ll recall, claimed the president’s “first response” to the 2012 Benghazi attack “was not to condemn attacks on our diplomatic missions, but to sympathize with those who waged the attacks.” This is just the latest chapter.

The partisan opportunism over the Bergdahl deal shouldn’t be surprising, but it is, a little bit. This wasn’t some wild radical idea of the Obama administration; it was driven by the Defense Department and signed on to by intelligence agencies. Although Congress is claiming it wasn’t given the requisite 30 days' notice of a prisoner transfer (more on that later), this deal or something very much like it has been in the works for at least two years, with plenty of congressional consultation.

And plenty of partisan demagoguery: In 2012 the late Michael Hastings reported that the White House was warned by congressional Republicans that a possible deal for the five Taliban fighters would be political suicide in an election year – a “Willie Horton moment,” in the words of an official responsible for working with Congress on the deal. In the end, though, Hastings reported that even Sen. John McCain ultimately approved the deal; it fell apart when the Taliban balked.

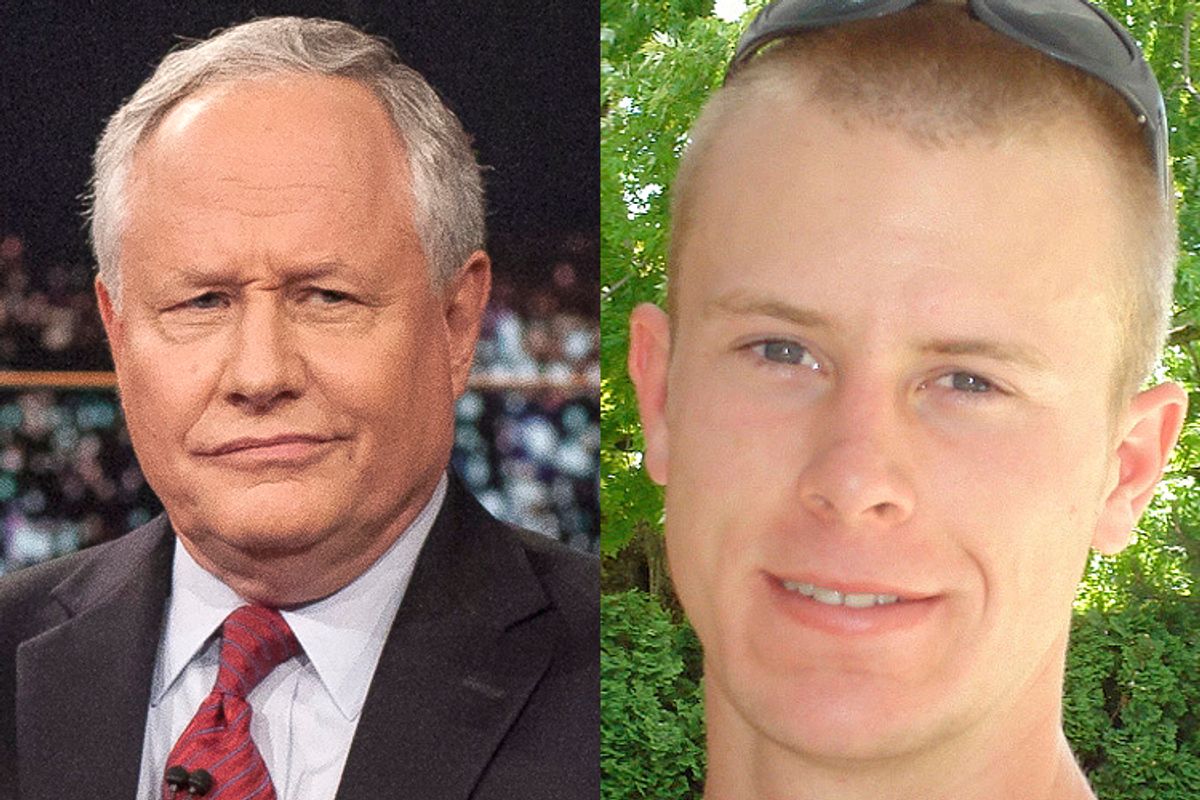

Two years later, the right’s official talking points are mixed: Some critics focus on rumors (buttressed by Hastings’ own sympathetic reporting on Bergdahl) that he was a soldier disillusioned by the Afghan war who deserted his post. Wrong-way Bill Kristol has dismissed him as a deserter not worth rescuing, while Kristol’s most prominent contribution to politics, Sarah Palin, has been screeching on her Facebook wall about Bergdahl’s “horrid anti-American beliefs.”

But missing and captured soldiers have never had to undergo a character check before being rescued by their government. Should they now face trial by Bill Kristol before we decide whether to rescue them? Is Sarah Palin going to preside over a military death panel for captured soldiers suspected of inadequate dedication to the war effort?

Other Republicans accuse the president of breaking the long-standing rule against “negotiating with terrorists” to free hostages. They’re wrong on two counts: The U.S. has frequently negotiated with “terrorists,” to free hostages and for other reasons. President Carter negotiated with the Iranians who held Americans in the Tehran embassy in 1979, unsuccessfully. President Reagan famously traded arms to Iran for hostages. The entire surge in Iraq was predicated on negotiating with Sunni “terrorists” who had killed American soldiers to bring them into the government and stop sectarian violence.

Besides, this isn't a terrorist-hostage situation, it's a prisoner of war swap, and those are even more common: President Nixon freed some North Vietnamese prisoners at the same time former POW Sen. John McCain came home from Hanoi. Even hawkish Israeli President Benjamin Netanyahu traded more than 1,000 Palestinian prisoners for captured Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit last year. Such prisoner exchanges are particularly frequent when wars are winding down, as Ken Gude explains on Think Progress.

It’s true that Bergdahl was never officially categorized as a “prisoner of war,” since the Pentagon apparently stopped using that designation years ago. But he was defined as “missing/captured,” which is essentially the same thing. And while the Taliban fighters who were released were likewise not formally designated prisoners of war, either, because of the odd, formally undeclared status of the war with Afghanistan, that’s what they were. As President Obama said Tuesday morning, “This is what happens at the end of wars.” Imagine the outrage if the president brought the troops home from Afghanistan but left Bergdahl behind.

It’s shocking to see conservatives argue that the Taliban should have the final word on an American soldier’s fate, even if he’s accused of desertion. There’s already an Army inquiry into the conditions of Bergdahl’s disappearance. “Our army’s leaders will not look away from misconduct if it occurred,” the Joint Chiefs chair Martin Dempsey said Monday night. Would John McCain, for instance, deny Bergdahl the right to military justice and leave his punishment to the Taliban?

Even some Democrats who had doubts about the 2012 Bergdahl release deal, like Sen. Dianne Feinstein, support the exchange executed last weekend. “I support the president’s decision, particularly in light of Sgt. Bergdahl’s declining health. It demonstrates that America leaves no soldier behind,” she said in a statement. Former CIA director Leon Panetta opposed the earlier deal because he felt it didn’t do enough to prevent the five Taliban leaders from returning to combat; this deal holds them in Qatar for at least a year. Panetta also lauded the deal Monday night because of Bergdahl’s use to intelligence agencies.

It may be that the terms of the Bergdahl deal merit congressional investigation, particularly about whether Congress was sufficiently consulted on the deal. Partly because of the ongoing efforts to free Bergdahl, Congress agreed to reduce its own requirements for notification of Guantánamo releases. But Obama, in a signing statement, signaled he believed even the relaxed law tied his hands, arguing that the president needed the flexibility to act quickly in certain situations when negotiating a transfer of Guantánamo prisoners. Yes, it’s true that Obama and other Democrats criticized George W. Bush’s wanton use of signing statements. This one can be debated. But Republicans didn’t wail en masse over Bush’s signing statements or his national security secrecy the way they are doing now.

Congressional investigations are one thing; shrill partisan hackery is another. "There's little that's actually new here," says Mitchell Reiss, a State Department official under President George W. Bush who also served as national security adviser to Mitt Romney. Reiss is right about the Bergdahl deal, but he’s wrong about the larger political atmosphere. What’s “new” here is a president who’s had his competence, his patriotism, even his very eligibility for office questioned from the outset.

Shares