Most fathers worry what their children think of them. But it’s a particularly delicate issue when you are a spymaster for the CIA. I’ve run clandestine agents in seven countries, including Chile, Argentina and Italy. I was involved in some of the agency's most high-profile operations -- the overthrow of Allende, the ouster of the Russians from Afghanistan and the Iran-Contra scandal.

By day, we were an embassy family, raising our kids in foreign cultures and foreign languages. Our children’s lives were fairly normal: schools, parties, trips. But my night job was as a CIA operative -- a second life my kids couldn’t know about until they were in their mid-teens. We needed to cut them in on the secret when they were old enough to handle the responsibility of keeping it to themselves but still young enough that they hadn’t stumbled across information that might disclose my true mission and then, unthinkingly, share it with their friends. Operatives try to find just the right age, when a kid’s judgment can be trusted not to compromise any operational cover, and by extension put their parents or their sources at risk.

Living undercover contains a touch of troubling deceit, and all parents worry how this will be perceived. I guess you could say I was lying, but I viewed it more narrowly as playing a cover role, and when my children were brought in on the clandestine activities, they usually took the news in stride and didn't see it as a malicious deception. They understood secrets had to be kept to protect our country and the spies working for us. It left no lasting distrust and didn't alter our relationship. In fact, I might have moved up a tiny notch in their estimation.

But breaking the news to children is an art form and, as a father of six, I didn't always get it right.

My operational strategy was to talk to my kids over the summer, after school got out and while we were posted back in the States. Sometime in June, I would orchestrate a one-on-one car ride to the Jersey seashore. I wanted to catch them alone where they couldn't bolt before I had an opportunity to make perfectly clear all the risks involved.

I waited until we started to cross the Delaware Memorial Bridge. That would give me an hour and a half to roll out my true profession. As the car barreled along, I would launch into a discussion of world events and the importance of national security. I would point to some specific area of the world where our national interest was at stake and explain how important intelligence would be for our leaders. I would slide into the important role the CIA played abroad. I can't say they were riveted, but they at least feigned attention. But when I got to the part about the role I played in the CIA -- they were all ears. They asked questions about risks and dangers, which I answered, and pretty soon, they settled it in their mind. Soon enough, we were back to business as usual. Onward to the beach.

At least that’s how it worked with the first two kids. But I caught Amy, our middle daughter, a bit late. She was 16, an age when children are becoming more focused on politics and exposed to the complexity of international relations.

When I told her I worked for the CIA, she let out a screech. “My father, an assassin!" she said -- not exactly the reaction I was anticipating.

It was also not how I hoped to be viewed by my daughter, especially with Father's Day only a few days away. I was caught totally off-guard, but we were moving at 60 miles an hour and there was nowhere for her to go.

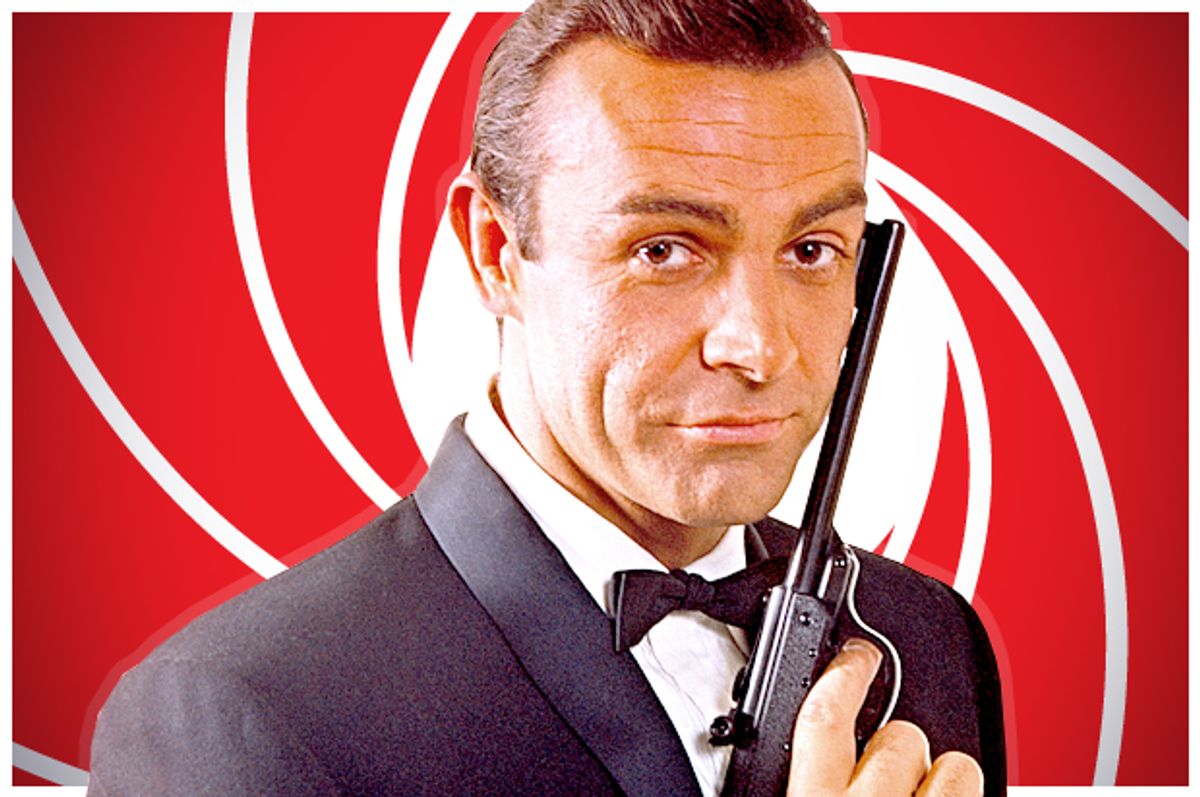

Once I recovered my balance, I painstakingly explained the real role of a CIA operative. Namely, collecting intelligence and carrying out special covert action activities as directed by the president of the United States -- which did not include assassination. As I slowly moved away from the action-packed movie version of a gun-toting James Bond and closer to a government bureaucrat who was simply serving the intelligence mission of the United States government abroad, the more I transformed in her mind from a dangerous assassin back to the less exciting and certainly not dangerous Dad. Which was precisely where I wanted to be.

By the time we got to the seashore, she had moved on to other topics, as teenagers are prone to do. I started thinking about improving the briefing for the next time around. My most important mission: to maintain my kids' love and respect.

Shares