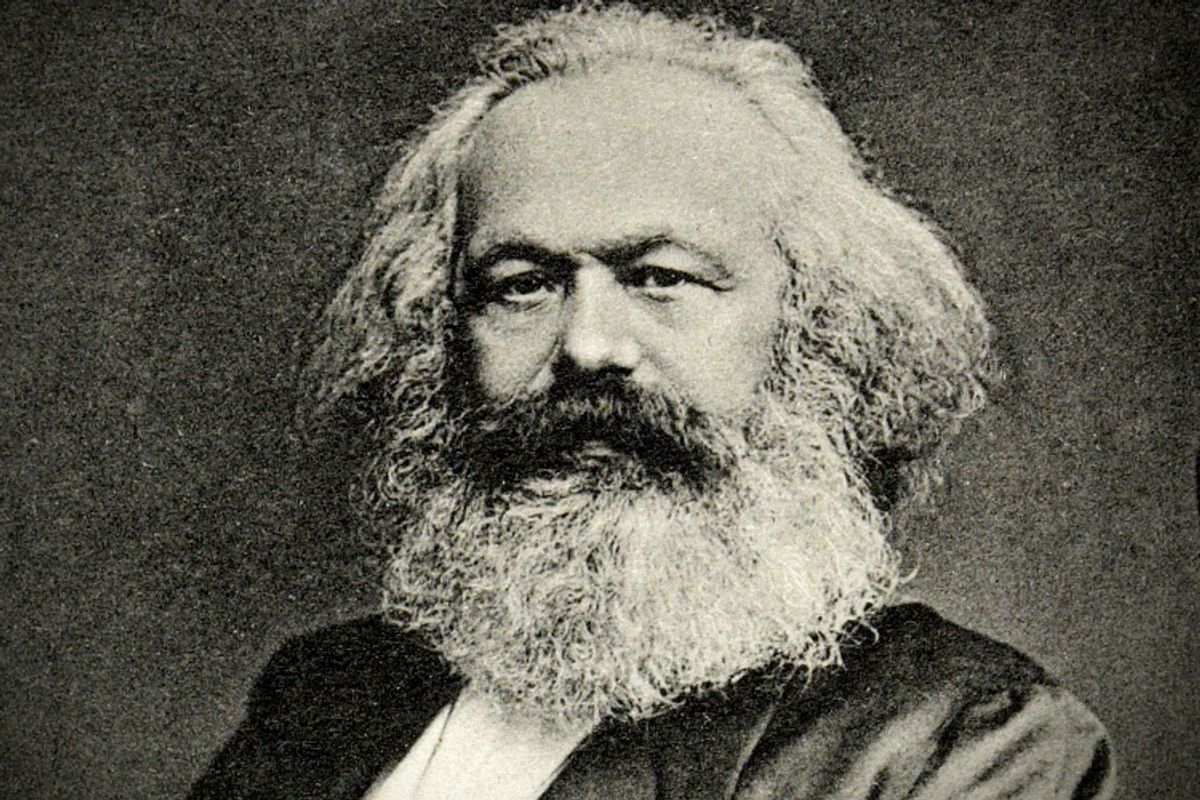

Karl Marx is on fire right now. More than a century after his death, the co-author of "The Communist Manifesto" still has the honor of being the first smear against ideas slightly to the left of Hillary Clinton. (See: Thomas Piketty.) Marx also graced the cover of the National Review as recently ast last month. Few other thinkers, and certainly few non-religious figures, can claim the honor of being so widely misappropriated by the political rearguard. But, while most people consider Marx only as a sort of intellectual boogeyman, the manifestation of everything evil on the left, he has much to offer a left increasingly divorced from the working class.

To that end, Marx actually is enjoying something of a renaissance on the left these days. Jacobin, a socialist publication that publishes many Marxist thinkers, was profiled by the the New York Times and boasts Bob Herbert as a contributor. Benjamin Kunkel’s recent compilation of essays, "Utopia or Bust," earned that author a profile in New York magazine, and the title “The Lena Dunham of Literature.” And that's not even to mention Thomas Piketty’s blockbuster work, "Capital in the 21st Century," which harkens back to Marx’s multi-volume magnum opus, "Das Kapital." The wave has even extended so far as Capitol Hill, where Sen. Bernie Sanders, D- Vermont, openly calls himself a “democratic socialist.”

Marx most certainly wasn’t right about everything, but he wasn’t wrong about as much as people think. A revival of his thought is good news for progressive America. It can give the left fresh arguments that were previously forgotten to history, and new organizing strategies that they’ve long since abandoned.

* * *

The first problem with the left that Marx might have noted is the wholesale abandonment of the working class. As Perry Anderson points out in his essay, "Considerations on Western Marxism,"

The extreme difficulty of language of much of Western Marxism in the twentieth century was never controlled by the tension of a direct or active relationship to a proletarian audience.

Increasingly, the left is dominated by what the German Marxist Rosa Luxemburg might call Kathedersozialisten -- or “professorial socialists.” These thinkers, frequently drenched in academese, talk and debate in a way almost entirely designed to alienate anyone who does not already accept their conclusions. The professorial left seems to have innumerable answers for those wondering what Lacanian psychoanalysis has to offer us, but can give us little guidance as to whether the Working Families Party should support Cuomo or run its own candidate.

"Manifesto" co-author Friedrich Engels's “The Condition of the Working Class in England” was a pioneering study of the working class. He and Marx both clearly saw the working class as the means to political power -- and viewed persuading them as the most important task the left faced. When Maurice Lachatre asked Marx if he would be willing to serialize "Das Kapital," Marx replied, “In this form the book will be more accessible to the working-class, a consideration which to me outweighs everything else.” One struggles, however, to imagine a latter-day Marxist champion like Theodor W. Adorno writing those words. The left abandoned the working class and the working class then abandoned the left. That needs to change.

Marx and Engels also offer the left a new way to discuss ideology. In his brilliant collection, "The Agony of the American Left," Marx(ish) historian Christopher Lasch writes,

The Marxian tradition of social thought has always attached great importance to the way in which class interest takes on the quality of objective reality… Lacking an awareness of the human capacity for collective self-deception, the populists tended to postulate conspiratorial explanations of history.

Lasch is arguing that, to a large extent, humans are biased toward the state of affairs that currently exists and then work backwards to justify it to themselves. That is, we're more likely to embrace a deeply unjust economic system, simply because it's the one we've always known. A recent study bears this out, finding that market competition serves to psychologically legitimize inequalities that would otherwise be considered unjust. Because many on the left, especially populists, do not understand ideology, they often write and argue as though the entire American political system is controlled by a small cabal of business or political leaders conspiring to fool the masses.

The implications of ideology are important and numerous. The left must not fall into the trap of believing that all Americans actually do share our views, but that a conspiracy of the wealthy, or the power of GOP framing, or the influence of money are preventing us from succeeding. To some extent, these things may indeed harm the left, but widespread ideology -- the automatic assumption of capitalism's unmitigated merit, for example -- is just as big a problem. We must win the war of ideas before we can win the war of democracy.

The great Italian politician Antonio Gramsci was well aware of the lure of such cabalistic conspiracies, but also of their limitations, and his idea about cultural hegemony led him to advocate for educating the working class. This task is difficult, but it will lead to more substantial progress than simply explaining away failures by complaining about the influence of the wealthy. The rich certainly have different interests than the rest of us, but Gilens and Page note in an often overlooked passage of their oft-cited paper on “American oligarchy,”

The preferences of average citizens are positively and fairly highly correlated, across issues, with the preferences of economic elites.

Groups like the Chamber of Commerce and other business-oriented organizations, on the other hand, have preferences that do not correlate with the interests of the middle class. But even with that caveat, the left should not overstate the extent to which Americans agree with the leftist economic critique. In an apt description of the American ideology, John Steinbeck noted, “Socialism never took root in America because the poor see themselves not as an exploited proletariat but as temporarily embarrassed millionaires.”

Finally, Marx’s moral critique of capitalism and markets has never been fully comprehended or considered by anyone (other than the socialists, of course) but the most ardent libertarians and a strain of thinkers broadly called communitarians. Broadly speaking, Marx’s critique of capitalism resembles the Catholic church’s critique: That by relying on greed and self-interest, markets degrade humans and encourage our worst impulses. Marx quotes Shakespeare’s "Timon of Athens":

This yellow slave

Will knit and break religions, bless the accursed;

Make the hoar leprosy adored, place thieves

And give them title, knee and approbation

With senators on the bench

Marx writes, riffing off of Shakespeare, “I am bad, dishonest, unscrupulous, stupid; but money is honoured and therefore so is its possessors. Money is the supreme good, therefore its possessor is good.” Jesus warned that the love of money is the root of all evil. This fact seems self-evident. Religious critics of capitalism have noted this core delusion for decades. Economist and Catholic E. F. Schumacher writes,

Call a thing immoral or ugly, soul-destroying or a degradation to man, a peril to the peace of the world or to the well-being of future generations: as long as you have not shown it to be ‘uneconomic’ you have not really questioned its right to exist, grow, and prosper.

With the exception of libertarians, who have tried to turn the immorality of capitalism into a sort of perverse morality (“greed is good”), most politicians and economists are entirely unconcerned with the fact that capitalism is based on a collective drawing upon our deepest desire: to exploit.

The underlying logic of capitalism is that if we all take our most primordial impulses and mix them up in the magical mechanism called “markets,” we are left with progress. Recent history suggests we may be left with only more ugliness. As G. A. Cohen writes, “the immediate motive to productive activity in a market society is (not always but) typically some mixture of greed and fear.” The participants in market transactions are not interested in fulfilling human needs -- they are interested in making a profit. Fulfilling human needs is one way to make a profit -- exploitation, the creation of desire through advertising or downright fraud are others. Human progress is an ancillary consideration, individual profit is the goal. Today, speaking in moral terms is not incredibly popular -- inequality is seen not as a moral issue in which a small class has a dangerous amount of power, but instead as an inefficiency to be corrected with a technocratic policy.

We don’t know for certain what Marx would say about the modern left. Its radicals often foster a poisonous aversion to pragmatism in favor of pious purity, its politicians are guilty of wholesale abandonment of the working class, and many of its leading thinkers have succumbed to a dreadful technocratism. Marx failed to account for the adaptability of capitalism and left little in the way of alternatives. In the end, this void was filled by murderers and fools. Marx, a deeply humanistic thinker, would certainly have abhorred the violence in his name some half a century after his death. But rational people do not blame Christ for the Crusades, nor Muhammad for 9/11 nor Nietzsche for the Holocaust. The taboo of Marx has prevented the left from learning his most important lesson; in the words of Gil Scott-Heron, “the revolution will not be televised.”

Shares