I killed my hillbilly father off with cancer — twice. The first time I was in kindergarten. During snack time, my teacher asked the class what we did for Father’s Day. Casey Owens described baking fancy cupcakes with butterflies on top for her dad. To upstage her, I blurted out that mine had died of cancer. Most of the kids didn’t know what cancer meant but had a vague notion it was the adult version of the boogeyman. After that, no one touched the graham crackers and juice. It was my first lesson in how to be a buzzkill.

The second time I gave my father cancer, I was on a plane to Chicago. The woman next to me had just lost her mother and was flying home for the funeral. She was about my age, mid-20s, and in and out of tears while traveling solo in the middle seat. When the man on the other side of her ordered a scotch and OJ, she clutched at my sleeve on the armrest. You’ve gotta be kidding me, she said, looking genuinely terrified. That was my mother’s drink! She looked more feral and alone than anyone I’d ever seen, so I told her I’d lost a parent, too, which seemed to bring her some relief. My father died of cancer.

The truth is I never knew my father, except that he was a redneck from Alabama named Aubrey Lee. I don’t know much about his family either. Whenever I try to picture what they look like, I see a bunch of caricatures: grubby-faced rubes hunting possum or whittling wood — recreational sports of the hillbilly Olympics. My father packed his bags and vanished into thin air when I was under a year old, leaving behind a space only mythology could fill. I hear he tried to kidnap me as a baby, stealing me from my crib and sneaking out through the sliding glass patio door. After I screamed and soiled myself for 24 hours, he handed me back over. That’s the thing about kidnapping infants; their neediness and lack of self-control make them incredible hostage negotiators.

I learned about death and disappearing from the soap operas my grandmother watched as she browned onions in the kitchen. It was a creative education in exotic maladies and suspicious endings. I studied resurrection, too. The first time I saw a character on “Days of Our Lives” return from the dead after being blown to smithereens by a woman possessed by the devil, I knew there was a lot of material I could use here. I had an arch-nemesis poison my father. I gave him an incurable blood disease. He also faked his own death for insurance money, got kidnapped by a gorilla after his plane crashed on a tropical island, and was held hostage in the sewers of Paris — all before I turned 8.

The legacy of my father’s whereabouts changed as I grew up and changed. He was everywhere and nowhere, both alive and dead. It was clear that asking questions about who he was or where he might be was unwelcome. My father’s disappearance was a classic magician’s trick: saw the lady in half. Though I don’t know which half I’m supposed to be looking for, my head or my legs.

One summer, when I was 9, I went with my grandmother to visit her sisters in Iowa. She and my great aunts were sitting around playing canasta and burning through jugs of Ernest and Gallo pink chablis. Sometimes when the men are gone and cards are on the table, old Catholic ladies turn spooky. The sisters started prognosticating like oracles about the disappearance of the Great Aubrey Lee as I hovered in the background looking at everyone’s hands. Words like "addiction," "prison," "death" swirled around the mosquito-heavy air. Maybe my father wasn’t just a deadbeat, but rather he was pulled under by something darker than his leaving. My grandmother, slurring over her sixth glass of wine, summed up her prophecy in a single sentence: “Your father smoked too much marijuana, and it killed him.”

As a child, I used to dream of writing Oprah to ask her to find my father. Unable to resist my heartfelt letter, she would hire a team of investigators to track him down. I imagined our reunion. We’d meet at a diner in the Deep South, coffee spoons cradling the distance between us, thick-ankled waitresses applauding next to a revolving bakery case, camera crews weeping into the condiments. And this sparkle, this dramatic flourish, would be the anti-venom for all those years of living in a poisoned well. All those gut-shot Father’s Days where his absence was anything but cinematic.

Every once in a while I try to find him. I Google his name, comb through public records. I’ve discovered his extensive rap sheet, mostly for possession and theft, spanning a handful of states since the early 1980s. No malevolent gorillas, no cancer. Just lists of defunct phone numbers and addresses drifting through cyberspace, all leading to disconnected places. I often feel closest to him after I’ve had too much to drink. I sometimes go through the numbers, Russian roulette-style, and drunk-dial the void. I have no script, just shaky hands and numbness. Each time, there is the monotone drone of the operator. The number you have dialed has been disconnected. The person you have dialed cannot be reached. The last time I called the void, a young child answered and I hung up immediately. I sat for several minutes, floating in a dull, viscous paradox, everything aching with both too much significance and no meaning at all.

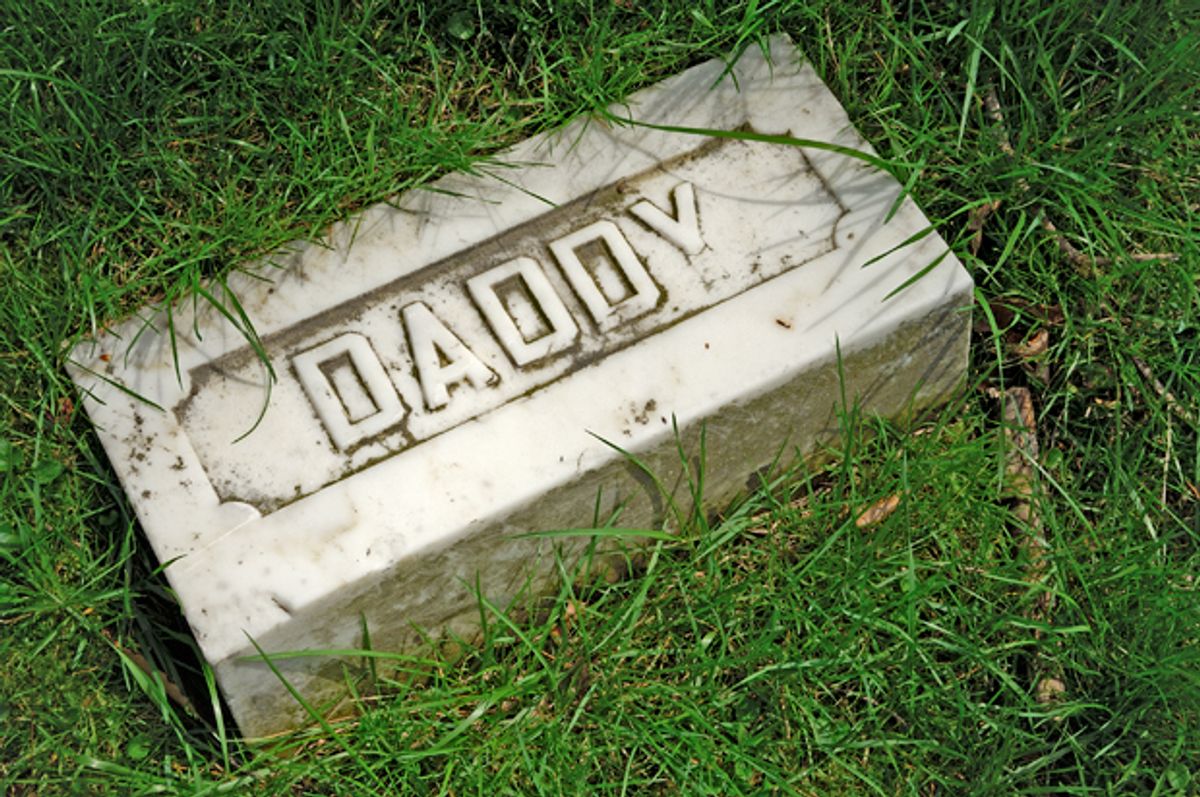

The first time I see a therapist, she tells me to write his eulogy. Start with what you know, she says. I look up all the synonyms for “hillbilly.” Rube, redneck, yokel. There are a bunch of charming terms, like hayseed, but I wonder about their ability to stand up to the lachrymose, slightly psychedelic tone of a eulogy for the unknown undead. If you want to be politically correct, the ACLU says you should use backwoodsman or backwoodswoman. And then there’s my favorite gem: hoi polloi, which calls to mind a bunch of country cousins dressed in Dior. Hick chic.

I write the words on Post-it notes and stick them to the refrigerator, to my steering wheel. I wait for something to speak to me but nothing does. I begin to think his eulogy is silence. The heaviness of things unsaid trying to dry on the laundry line of time, stretching from the home where I was born to an infinite unknown. Sometimes I imagine I’m standing in a field of wild prairie grass, watching my father, the not-so-dearly departed. He sits on a crumbling front porch, coaxing rye out of a bottle, a hound’s jowls draped over his boots.

I’ve only seen two photographs of Aubrey Lee: One is a sepia-toned shot of him holding me as a baby in 1979; the other is a mug shot from June 2013, from a local newspaper in Cullman County, Alabama. My friend sent me a link to the article via text. Is this your father? It was an article about a massive drug bust, and Aubrey Lee’s photo was at the top. Aquafresh green prison stripes, bald dome, scraggly ZZ Top beard. My friend sent another message: I don’t see the resemblance to you …

I have only one story about my father. My mom told me that one night he flew into a rage, grabbed a frying pan and shattered her fish tank. She insists they were tropical fish she had individually named, just to punctuate her sense of loss. I imagine brilliantly hued fish with name tags floundering in the blue glow of late-night television.

My mom, who was pregnant with me at the time, raced to gather the fish with newspaper and deposit the diaspora in a bathtub of running water. Ten minutes into the rescue mission, she realized she forgot to plug the drain. She stared helplessly as the smaller fish disappeared; the larger ones jumped under the gushing faucet, their bodies smashing into shards of glass. Defeated, my mom walked back to the living room and waited for the mass piscine grave to stop thumping around her, her bare, cut up feet dripping blood into the shag carpeting. Sometimes I think my mom’s still there — with me in her belly, slowly bleeding into the ground.

As I grew up, the frying pan still hung in our kitchen, next to the crocheted potholders and Mrs. Dash. Though it was little used, it lingered, collecting a thick coating of grease. Every once in a while I would take it down and feel its weight. I would invent stories about my father as I gripped the wooden handle. Mythology born from a God with Teflon skin. I would imagine the half of me I didn’t know, feel for its outline and shape. I have his hair, his height. I have his yen for excess and leaving, which I keep muzzled and chained like an animal of unknown temperament. I have his name and his hillbilly bones. Aubrey Lee, a man made up of smoke and dust. A diseased limb on a defiled tree. A fish murderer responsible for the genocide of a small artery of Atlantis.

Instead of his eulogy, I wrote a eulogy for the missing. Not only for those gone, but for those never here. For the undead ghosts roaming the halls of addiction. For lives that are lost but still living. I dedicated it to all who don’t know where half of who they are comes from. I spoke of how I feel tickled to pay the electric bill, eat vegetables, smile kindly at a stranger. How I marvel at these tiny, mundane acts of normalcy, and feel proud, like I haven’t given in to his missing. I buried the eulogy with his photograph and raised a glass. To Aubrey Lee. To all of us with unknown blood, a family of half families. May we find our pound of flesh among the flowers.

Shares