“By the Grace of God,” the English used to say, when asked by what authority their monarch ruled. “Divine right” was the answer, and that was that – you didn’t have to like the queen, but God did, and that’s why she was in charge.

Simpler times, those were.

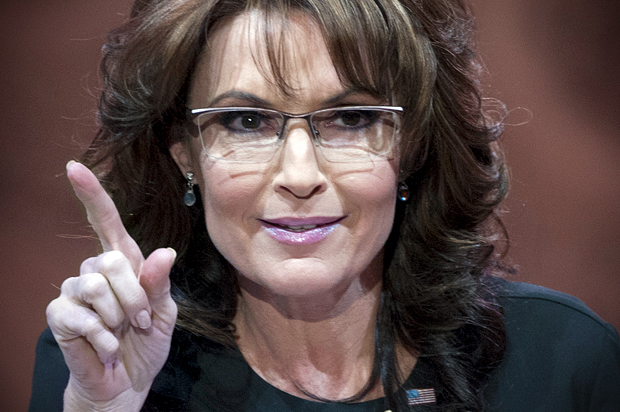

Today, former GOP vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin announced her belief that President Obama should be impeached. Last week, Speaker of the House John Boehner announced his intention to launch the first congressional lawsuit against the executive branch since United States v. Nixon. Days later, the Republican Party of South Dakota became the first state-level party organization to formally call for Obama’s impeachment.

If some Republicans are to be believed, the only rationale behind Congress’ tamer lawsuit route is feasibility: “If we were to impeach the president tomorrow, you could probably get the votes in the House of Representatives to do it. But it would go to the Senate and he wouldn’t be convicted,” congressman Blake Farenthold told BuzzFeed last year.

The occasional call is nothing new. Presidents from Abraham Lincoln to Franklin Roosevelt have faced the fringe demand for congressional removal, and despite two successful efforts in the House (against Andrew Johnson and Bill Clinton), none has ever seen the bad side of a subsequent Senate trial. President Obama will not be impeached; despite their bluster, the GOP-controlled House will never even propose a trial in earnest. The Clinton years taught them well enough what happens when such an effort backfires and you become the guys who just wasted a year of the country’s time.

What ought to concern us is not the serious possibility of the president being removed from office, but the sense of what – in a world where such a conversation occurs at all – suddenly seems reasonable by comparison. Consider an interview earlier this year, in which Fox News host and Santa Clause ethnicity specialist Megyn Kelly asked Mitch McConnell why he and the rest of the congressional GOP hadn’t seriously explored the “meaningful option” of impeaching President Obama for vaguely defined “abuse of power.”

It doesn’t matter that McConnell said they wouldn’t: That the question was even asked on a major television network by a prominent (if not necessarily respected) member of the press to one of the most powerful figures in the federal government reflects something more than just fringe lunacy. It is indicative of a broader trend in our civic culture, one more subtly (but perhaps tellingly) betrayed in Senator McConnell’s then-contention that simply defunding every executive initiative and refusing to let the country function while President Obama remains in office would be a comparatively reasonable, “less dramatic” option.

* * *

We’ve gotten into the habit of delegitimizing our presidents — not just contesting their election or pushing back against their policies, but denying their very claim to the White House. From the farcical (birthers) to the faux-serious (“anti-American socialist!”), we’ve moved beyond mere opposition and into a deeper civic sickness, where casting aspersions on the policies of an opposition president has given way to challenging his very right to implement those policies.

It didn’t start with Barack Obama. This new kind of cynicism has been gaining ground for years. The conspiratorial style is catching. Growing up during the Bush administration, I joined plenty of my fellow leftists in righteous conversations about hanging chads and Diebold-stolen votes. Before that? It was eight years of Bill Clinton: Whitewater murder suspect and blow job perjurer.

That isn’t to say it doesn’t make a certain kind of sense. The impulse to delegitimize the president serves as a useful solution to an old dilemma in American politics: How do you respond to a leader who is at once enemy and ally — someone who was bitterly opposed in his ascension, but having nonetheless prevailed, is now not just their candidate, but your president, as well?

As cynical as we’ve become, Americans still retain a certain reverence for the presidency. Watergate eroded it some, sure; and the ensuing soap operas — from Iran-Contra to Monica to Tallahassee 2000 have certainly tarnished the brand. But within our civic consciousness, the presidency retains a transcendent air, an office occupied by a politician, but still not entirely political. The president is the commander-in-chief. He is the head of government, yes, but he is the head of state as well. The office still retains that luster, and across table from prime ministers and kings, he speaks for all of us. There is a reason we still don’t tolerate his challengers attacking him when overseas.

But pressed by a modern world into an unprecedented form of zero-sum politics, the tension between “our guy abroad” and “their guy at home” proved more difficult to sustain. So the delegitimizers found a work-around: If you can’t strip the presidency of its protective insulation, you can strip it from a chief executive by insinuating that he isn’t really the president in the first place. And that’s when the loyal opposition becomes a crusade against occupation, poisonous to a functioning government.

It’s a dangerous game. When the “grace of God” gave way to “the grace of an electorate,” it was vital – if people were to be governed by consent – that that consent, once given, be respected. When we allow ourselves to start believing that consent is counterfeit whenever we disagree with our leaders, the national experiment breaks down. The well is poisoned. Wars against usurpers involve no compromise, and so we see endless gridlock. We see politics as trench warfare. We see a polity where reaching across the aisle is a betrayal and defunding every initiative is the “reasonable” response. We see a system in which every year is little more than a battle to reclaim the throne from a fraud — the very thing we broke with Britain to avoid.

God save the queen.