It's about a month from release -- and yet the new film "The Giver," directed by Phillip Noyce, seems like just about the only thing that can save this grim summer movie season. At a time when just about the only thing that consistently works in Hollywood is dystopian teen fiction adaptations -- just ask Jennifer Lawrence or Shailene Woodley -- "The Giver," based on a 1993 novel by Lois Lowry, is the OG.

"The Giver," a fixture of school curricula across the country, is the story of a young boy, Jonas, whose society assigns specific careers to each citizen based on their strengths. Jonas ends up becoming "receiver of memory" -- the one person who holds in his psyche all the joys and pains of the world before it became regimented and orderly. He receives the memories from the Giver, played in the film by Jeff Bridges, and has to decide whether what he's learned of all the tragedies of the past merited society giving up free will.

We gradually learn, on the page, just what his society has given up -- everything from weather to sex to colors. On film, though, it will be clear from the first frame that this world is in black-and-white, instead of a slow reveal. That's hardly the only change; as is customary, the teens in the film have been aged up a bit, a decision that has been controversial. (Brenton Thwaites, a 24-year-old Australian, plays Jonas; other characters are played by Meryl Streep, Katie Holmes and Taylor Swift.)

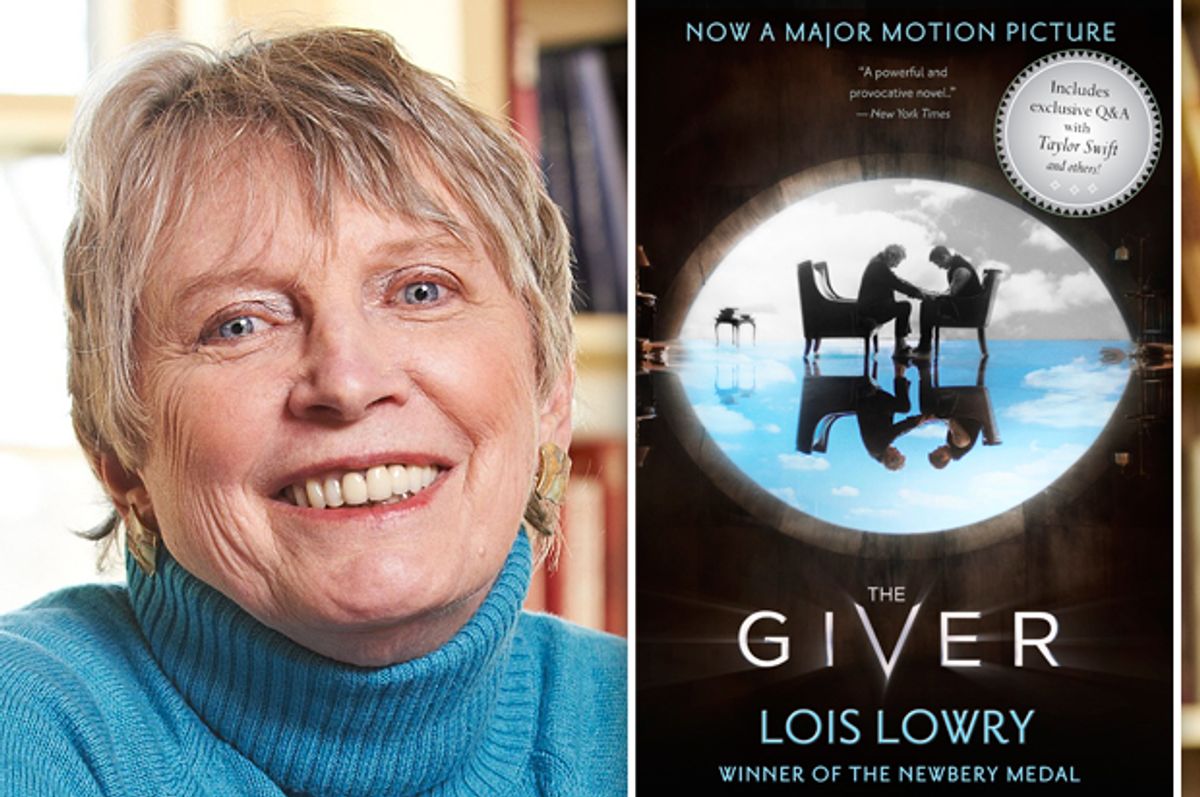

But controversy aside, the film seems to be in good hands. Lowry, a prolific novelist who's put out three sequels to "The Giver" as well as the Holocaust novel "Number the Stars," consulted on the adaptation; Noyce, the director, has had a long career including films as diverse as the thriller "Dead Calm," the historical drama "Rabbit-Proof Fence," and the Angelina Jolie spy vehicle "Salt."

Salon spoke to Lowry about the prospects for the movie -- how it fits into, and how it influenced, a market now full of stories about teens making big decisions in far more restrictive futuristic societies. Take heart, fans of the novel. As Lowry put it: "The things I could have been most upset by, I wasn't."

Did you think much, while writing or at any other point, about the degree to which your book was "cinematic"?

I think it was -- I don't recall that I thought about it in those terms. When I'm writing a book, I think of a book, not a movie, though a couple of my other books have been made into TV movies. When they first showed an interest, though, I became aware there was very little description and very little visual stuff, very little action. I then realized that a screenplay -- and there were many written -- was going to have to make substantial changes. Each time a screenplay was written and people were involved in the adaptation, they tried to remain true to the concepts.

Were you worried that changes would alter the meaning of your work?

It hasn't changed so much that I needed to anguish. There's action added and, of course, there had to be. And the characters are a little older and that made me nervous. I asked them if they had to make the characters teenagers, could they not make it a romance? And it's not that. It's wistful -- between the very attractive young girl and the lovely boy, that they could have entered into a romantic situation. Because of circumstances which are true to the plot, it's not going to happen. The things I could have been most upset by, I wasn't.

Between "The Hunger Games" and "Divergent," dystopian fiction for young people is everywhere these days. Do you take credit at all?

I don't take any credit, but people give me credit. They say "The Giver" was the first YA dystopian novel. I majored in English and read classic dystopian literature, "1984" and "Brave New World" -- but that was a long time ago. I didn't set out to do a dystopian novel, it just became that. And now, for whatever reason, every third person wrote a dystopia. It was a trend and it's ending now, and all of us writers would love to know the next trend so we could follow it. I don't know how to account for it.

What accounts for the trend of dystopian fiction these days, do you think?

I don't feel I follow trends, because I don't read YA literature. I'm very rarely aware if there's a trend. I don't know what it is. That frees me to go where my imagination takes me. In 1992 or '93, whatever year it was, it took me into the future. I think it's probably a mistake to follow a trend. It's an oxymoron -- by the time you follow a trend, it's too late.

If you don't read YA, why are you interested in writing it?

I sit down and write a book. And my books tend, with a couple of exceptions, to have a young person as a main character. I'm not sure why that's the case. I have four kids, four grandchildren -- kids have always been of interest to me. But I don't tend to be aware of genre. I don't think about that. I go where the story takes me. Because they made the characters a little older in the movie, it has a different flavor than the original book where characters are 12. And there are two adult stars -- Jeff Bridges and Meryl Streep -- whom people just want to see together in a film.

Did you know as you were writing "The Giver" that it was somehow different from your other books? It's certainly by far the most widely read.

If we as writers could predict what readers grab on to, we would write it. I know from the beginning, from first publication, it acquired an audience my previous books had not. Suddenly, for the first time, I began getting letters from different segments of the audience, and letters from adults more than ever before. I don't know how they came to the book. Something was speaking to different people I hadn't had before. And it has continued. The book has been out for 20 years, and I still get letters or email every day.

Do you find that in the years since its publication, the book's come to seem more politically relevant? Do you see aspects of the book in contemporary life?

Some things. Starting after 9/11, when we had suddenly to be desperately concerned with our own safety in ways we hadn't before and compromises had to be made politically. Certain freedoms were curtailed that we'd always had, and that was done in the name of safety, and that's what had happened in the community. Compromises had been made with the most benevolent intentions, we do see that.

Did you have a political intent when you wrote it?

I've had readers, and read articles in magazines, in which they find political sentiments on both ends of the spectrum. People who are very conservative and feel they represent family values find that in this book. And ultraliberal people -- the same thing will hold true at the other end of spectrum. It happens also with theology, they'll find it. I've had very conservative Baptist churches use the book as part of religious curriculum. Also ultraconservative religious groups want it banned. It's something that speaks to whomever wants to hear it. I have no control over that. I did not plan any specific political or theological interpretation, but people seem to find it.

Shares