A major outbreak of Ebola in West Africa is continuing to take lives, with no easy end in sight. It's certainly a crisis -- the deadliest Ebola outbreak in history, described by a senior official with Doctors Without Borders as being "totally out of control" -- but it's a crisis with parameters, some of which tend to get overblown by an overhyped media and hysterical rumors. Concern for the people in Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia and Nigeria suffering from this terrible disease, and for the U.S. aid workers who have fallen ill, is warranted; panic driven by misinformation is not.

Below, a quick primer on what you do and do not need to worry about as things currently stand:

The real threats

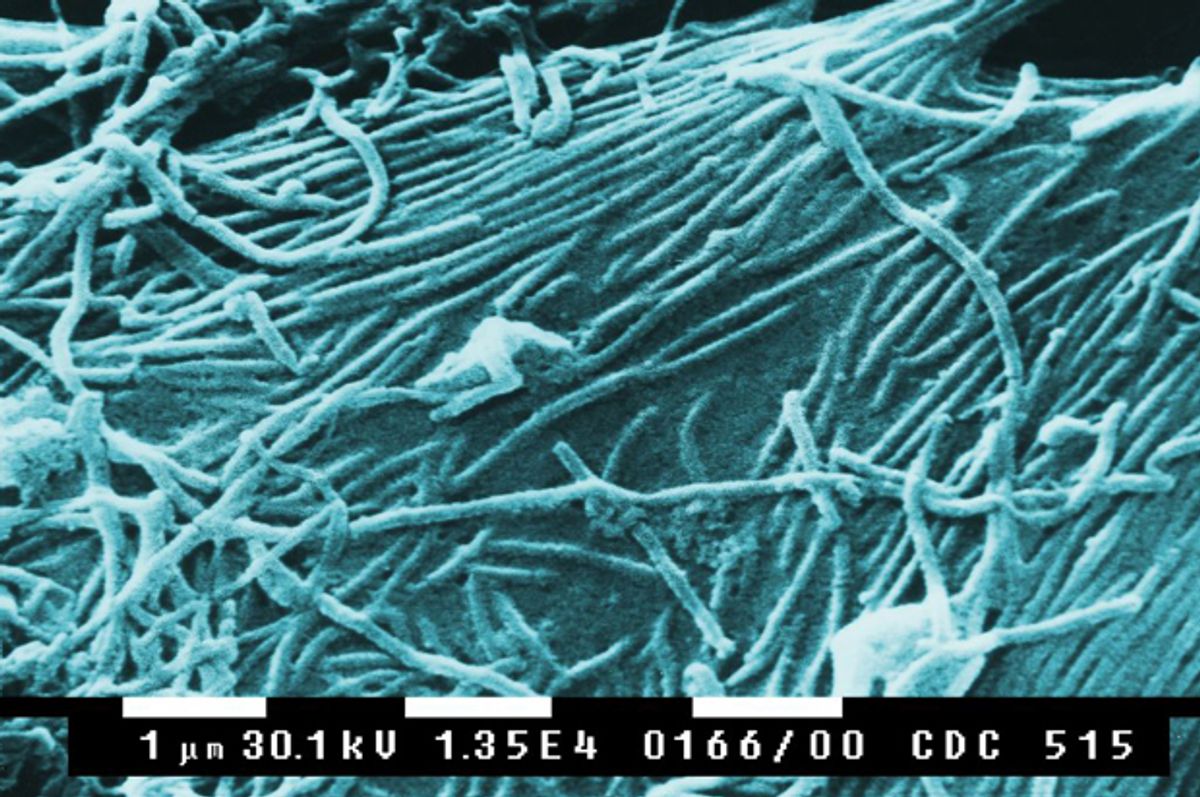

1. Ebola is a horrible disease

Of all the diseases you don't want to get, Ebola lands near the top of the list. (Quoth journalist David Quammen: "Ebola is more inimical to humans than perhaps any known virus on Earth, except rabies and HIV-1. And it does its damage much faster than either.") The symptoms start out ambiguous -- fever, headache and sore throat, then vomiting and diarrhea -- but, in the later stages, turn horrific. Accounts differ on just how horrific -- yes, some patients bleed from their eyes, but it's probably not like how you're imagining it.

The fact remains that it's deadly: As of Monday, according to the World Health Organization, there have been 887 deaths in Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia and Nigeria.

2. Containing it is a challenge

The conditions that have made West Africa a hotbed for this outbreak have been in place since the virus first emerged this winter: It's widespread and occurring in heavily populated urban areas, making containment a challenge; the affected areas haven't experienced Ebola before, leaving health workers unprepared (and lacking the resources) to protect themselves and others; and a climate of fear and mistrust surrounding this unknown is making health workers' tough job even tougher. In order to contain the outbreak, experts say, they need to be able to track every last person who's become infected, along with everyone they've been in contact with, including after their death: Some traditional burial rites involved washing dead bodies by hand, which is another way that the disease can spread.

3. There's no vaccine, treatment or cure

What makes the structural barriers listed above so important is that dealing with them -- through an influx of resources, education and the hard work of dedicated individuals -- is the only real way to stem the epidemic right now. Patients benefit from good medical care: Doctors can only treat the symptoms, but by so doing they can lower the death rate from 90 down to about 60 percent. But despite there being some promise in experimental drugs and potential vaccines, nothing we've got right now has been proven effective or ready to be rolled out on a large scale -- again, many hospitals treating patients don't even have access to the basic resources needed to help protect the virus from spreading. The Onion, as usual, wasn't too far off base with a recent headline ("Experts: Ebola vaccine at least 50 white people away"); as Vox puts it: "right now, more money goes into fighting baldness and erectile dysfunction than hemorrhagic fevers like dengue or Ebola." But the good news is that Ebola is not known to be transmissible through the air, or by any means other than direct contact with the bodily fluids of someone who's infected, which is why those on the ground are continuing to focus on keeping that from happening.

The not-so-real threats

1. Ebola patients are coming back to the U.S.

The second American patient to contract Ebola in West Africa returned to the U.S. this morning, a situation that's surely scary for her, her family and the doctors treating her at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta. But getting to a Western hospital ensures she'll get the best possible care, and the entire process of getting patients here is incredibly controlled: according to the CDC, the agency has "very well-established protocols in place to ensure the safe transport and care of patients with infectious diseases back to the United States. These procedures cover the entire process -- from patients leaving their bedside in a foreign country to their transport to an airport and boarding a non-commercial airplane equipped with a special transport isolation unit, to their arrival at a medical facility in the United States that is appropriately equipped and staffed to handle such cases.”

The hospital, too, stresses that it's more than prepared for this: “Emory University Hospital has a specially built isolation unit set up in collaboration with the CDC to treat patients who are exposed to certain serious infectious diseases,” officials said in a statement. “It is physically separate from other patient areas and has unique equipment and infrastructure that provide an extraordinarily high level of clinical isolation. It is one of only four such facilities in the country."

The idea that people who don't yet know they have Ebola could be arriving back in the country -- as occurred Monday when a potential (and, it turned out, false) case was reported in New York City -- is frightening, but officials stress that while this is definitely something that can happen, the general public still has little to fear. "We have exactly what's needed to control Ebola," expert Jonathan Epstein told Mother Jones, "and that is to rapidly identify a case with confirmatory diagnostic testing," and, again, protocols for isolation. "I really do have a high confidence that if cases do make it to the United States that they'll be identified, and traced back, and addressed."

2. It's contagious

... but not "Contagion" contagious

This question posed by readers of NBC News is emblematic of the degree to which Ebola hysteria is being fueled by our collective fears: "What if the plane [patients being transported back to the U.S.] are on crashed?"

"That would be a terrible thing for the people on board,," responds health writer Maggie Fox, "but Ebola virus is not going to somehow escape into the atmosphere and spread, nor is it going to crawl along the ground and infect unsuspecting people."

CDC director Tom Friedan emphasized two points about how the Ebola spreads: It can't be transmitted from someone who has been exposed to it but doesn't become sick; and proper isolation, which all advanced hospitals in the U.S. are trained and prepared to provide, will almost certainly prevent a large-scale outbreak in this country.

3. It's "out there"

Scientists aren't exactly sure how and why this particular (and particularly deadly) strain of Ebola, formerly only found in Central Africa, emerged in Guinea -- the leading theory is that it's linked to fruit bats -- but this remains a situation centered in West Africa. No matter how many Republican congressmen suggest that migrant children attempting to enter the U.S. from Central America may be carrying Ebola, migrant children attempting to enter the U.S. from Central America are not carrying Ebola.

Shares