Some people knew it was coming.

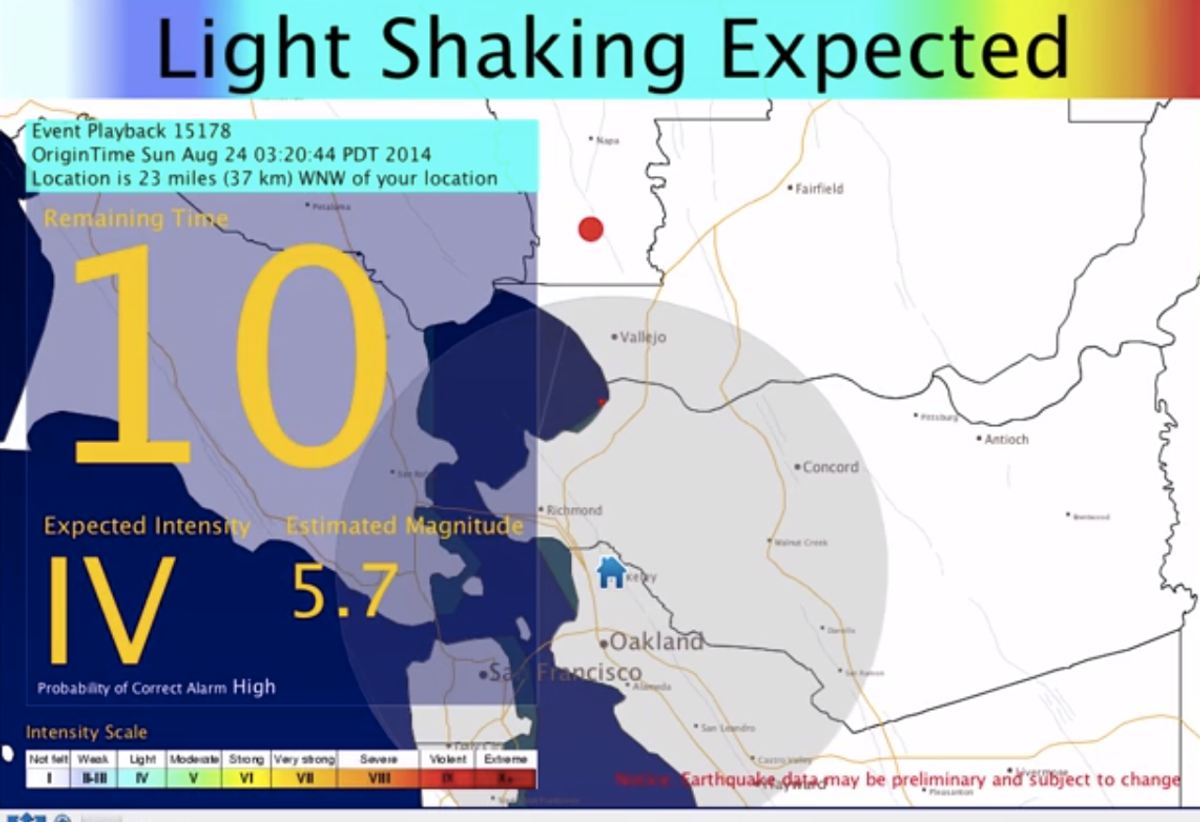

Sunday morning, 10 seconds before Northern California was rocked by a 6.0 magnitude earthquake -- the strongest to hit the region in 25 years -- computers running beta software from the Berkeley Seismological Laboratory received this warning:

Kind of panic-inducing, right? Ten seconds is shockingly little time to prepare for the ground shaking beneath you (users in San Francisco, Oakland and San Jose got a bit of extra time). But it's also kind of extraordinary, proof of concept that early warning systems for natural disasters of this sort are possible.

Berkeley's ShakeAlert system works by detecting P waves, the seismic tremors that precede the more destructive S waves, and by taking advantage of the fact that communications systems move more quickly than either. This was the first time that it was successfully tested during a major earthquake, and it worked as intended.

Seismologists may never be able to predict future earthquakes, so this little bit of advanced warning is a lot better than nothing. And the bigger the earthquake, Richard Allen, director of Berkeley's Seismological Laboratory, told National Geographic last year, the more warning the system would be able to give: up to a minute for an 8-magnitude quake, and up to 5 minutes for a magnitude 9. (Distance matters: According to the U.S. Geological Survey, no warning would be possible within 20 miles of an earthquake's epicenter.)

With that kind of advance notice, trains could brake to avoid derailment: a representative from Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART), which uses the system, told Motherboard that it received the alert and could have stopped or slowed trains had any been running at that hour. Elevators could open their doors. Firefighters could open their garages. People could take shelter, or grab their wine bottles. In a recent editorial for the journal Nature, Allen argued that the next "big one" -- a quake of at least 6.7 magnitude -- is inevitable, and urged California to make like Japan, China, Taiwan, Mexico, Turkey and Romania and install early warning systems. "The first line of defence in the United States is a robust building code to prevent structures from collapsing," he wrote. "But now, the information revolution allows us to develop real-time responses to minimize casualties and damage." He cited as an example a Japanese chip manufacturer that invested in both building improvements and an early warning system after experiencing $15 million in losses; in two similar, subsequent quakes, that damage was reduced to $200,000.

"Rather than waiting until the next big quake galvanizes political action," he wrote, "I believe that we must build an alert system now."

In September 2013, California Gov. Jerry Brown signed a bill to create a statewide early alert system like this. According to Allen, installing and running it would cost about $120 million for the first five years, and $16 million a year after that: about twice the state's current seismic monitoring budget. So far, however, the state has failed to fund it.

Shares