Continued anger over the death of Mike Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, has people questioning why an unarmed 18-year-old would be gunned down in the street. While Brown’s death has caused some Americans to begin to confront the dehumanization of black bodies and militarization of local police, the legacy of white supremacy and guns in this country remains tragically unappreciated. The United States has more guns and gun deaths than any other developed country. A recent study from the Pew Research Center indicates that there is one gun for every man, woman and child in the United States. The data also reveals that most of these gun owners are white men.

At the National Rifle Association convention this April, a strong message of fear was peddled to its mostly white male members. NRA executive vice president and CEO Wayne LaPierre welcomed guests to what he called “the biggest celebration of our American values” before accusing the media of attacking the Second Amendment. He then shared a message of the righteousness of gun ownership to defend against a scary world of “terrorists and home invaders and drug cartels, car-jackers and knock-out gamers and rapers, haters, campus killers, airport killers, shopping-mall killers.” LaPierre argued that the world is going to pot and “the surest way to stop a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun.”

Following that playbook, Ferguson police illustrated their support of officer Darren Wilson when they withheld his identity and launched a smear campaign against Brown by releasing a puzzling video from a convenience store that had nothing to do with Wilson's stop of the teenager. They were, by all appearances, trying to build a case that Wilson was the "good guy with a gun" of LaPierre's hero fantasies.

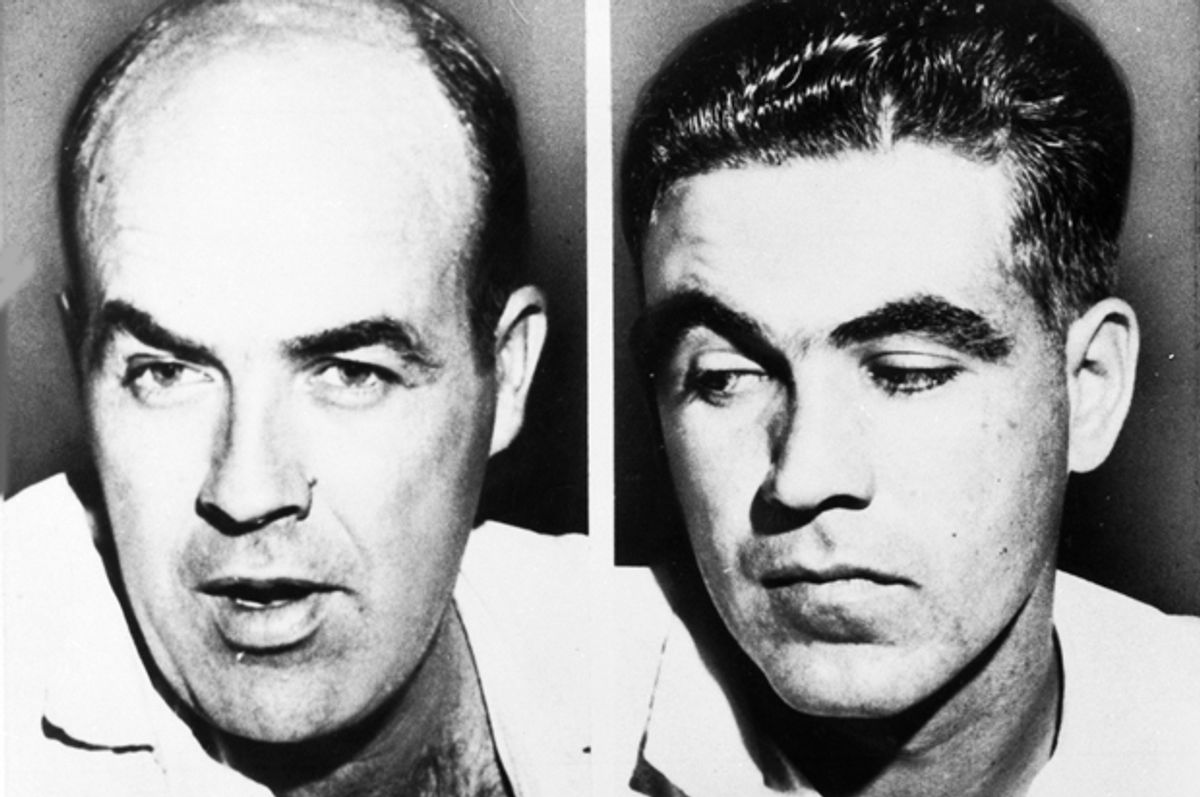

But the horrific shooting of Brown was part of a long national history of racist violence, following such disasters as George Zimmerman's killing of unarmed teen Trayvon Martin and the abduction and the decades-old murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till. In all three cases, white men exacting authority killed young black men or boys who they believed defied them. Remarking on these patterns, Ladd Everitt, director of communications at the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence, tells Salon that the modern NRA and the gun rights movement stands for “the restoration or maintenance of [white male] privilege in society and the gun [as] the guarantor of their power in society.”

Other unarmed victims of police violence like Jonathan Ferrell and Oscar Grant, to name a couple, reflect how little we consider this kind of violence as part of the epidemic of gun violence. This erasure also reinforces the message that black people can be killed by public and private citizens with little to no consequence in the criminal justice system -- especially without civil unrest.

Throughout American history guns have been instrumental in maintaining white supremacy. The Southern Poverty Law Center notes growing diversity -- America will be mostly non-white by 2043 -- as a factor in the increase of white supremacist groups. In fact, past moments of cultural change have yielded violent opposition by white citizens.

Until the end of the Civil War and the passage of the 14th and 15th Amendments in 1868 and 1870, respectively, African-Americans were not protected by the Constitution or the Bill of Rights. Indeed, the Dred Scott decision of 1857 stated African-Americans, whether free or enslaved, were not considered citizens as “beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race.” Ironically Dred Scott, the slave who sued for his freedom in St. Louis, is buried just miles from Ferguson in Calvary Cemetery on West Florissant Avenue.

After Dred Scott, it was only the 14th and 15th Amendments affirming black citizenship and the right to vote that would reclaim African-Americans’ humanity under the law. But black citizenship remained limited and contested under enduring white supremacy. Many anti-government white citizens, particularly in the South with its black majority, but elsewhere too, did not want black people to have guns, a right afforded to them under the Second Amendment.

Law professor Nicholas Johnson discusses some of this history in his book “Negroes and the Gun,” in which he chronicles an often bloody history of African-Americans striving for armed self-defense in post-Civil War America. Today, as in the past, racist state agents and/or paramilitary groups were often a source of violence in the black community. Meaning, when whiteness seemed to be threatened, white supremacists would use gun violence to “restore order.”

In a strange way, Johnson’s book is a palatable repackaging of Robert F. Williams’ classic text “Negroes With Guns.” Williams is often remembered as the inspiration behind the Black Panther tenet of armed self-defense, a position linked to this history of racist violence. Though armed self-defense was a deeply resonant position in the past, today 68 percent of African-Americans support stricter gun laws.

According to lawyer, legal scholar and former chairwoman of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights Mary Frances Berry, “I don’t think that the people who enacted the Second Amendment were thinking about black people … many things in the Constitution aren’t about black people at all because black people weren’t even considered to be people.”

To best understand the phenomenon of gun violence during demographic shifts where white supremacy is threatened, we can look to the Colfax Massacre. In April of 1873 in Colfax, Louisiana, a mostly black state militia protecting a local courthouse after elections was massacred by members of the White League, one of numerous white supremacist groups bent on halting Reconstruction. The assault resulted in the murder of 100-plus militiamen and only three whites. Up until this point, the federal government legally protected the right to self-defense and gun ownership for blacks, but the racist backlash to emancipation was perceived as too great for the fragile nation.

The incident led to an infamous Supreme Court decision with United States v. Cruikshank, which annulled charges of murder against a handful of white plaintiffs from Colfax and concluded that the federal government had no oversight in assuring the security of former slaves.

By failing to reinforce the rights of blacks in the aftermath of the Colfax Massacre, the federal government set precedent for further denial of African-American rights until the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Act of the 1960s. Berry affirms, “By and large the white reactionaries using violence, killing people, harming them and driving them away from work, took over. Yes, it was legal for everybody to have weapons [but] any black person who had a weapon was suspect” -- and subject to any form of intimidation.

What Berry helps us understand is that when the “other” is perceived as displacing white male supremacy that person can be eliminated with the pull of trigger.

The moment we are in is not unlike the fear-mongering times of Reconstruction or the countercultural shifts of the civil rights era. America is in a pivotal place of transition from predominantly white to increasingly black, brown and mixed race. From a nation of men controlling power to one with more women claiming a seat at the table. From a nation of heteronormativity to that of multi-ethnic, gay and blended families.

For the NRA, officer Darren Wilson, George Zimmerman and others like them, the gun is what Berry calls “a symbol of their ability to correct people and perpetuate their idea of what America means, which does not include black people.” However, equal protection under the law is the first step to dismantling our addiction to guns and unnecessary violence. It’s not just about lone gunmen or the emotionally disturbed or rogue cops; it’s about a legacy of white supremacy and guns.

Shares