Is computer code art? What binds two different acts of creation -- writing fiction and programming a computer -- together and what sunders them apart? To successfully answer such questions, one needs to be both a superlative writer and a smart programmer, equally at home building worlds out of words and software code.

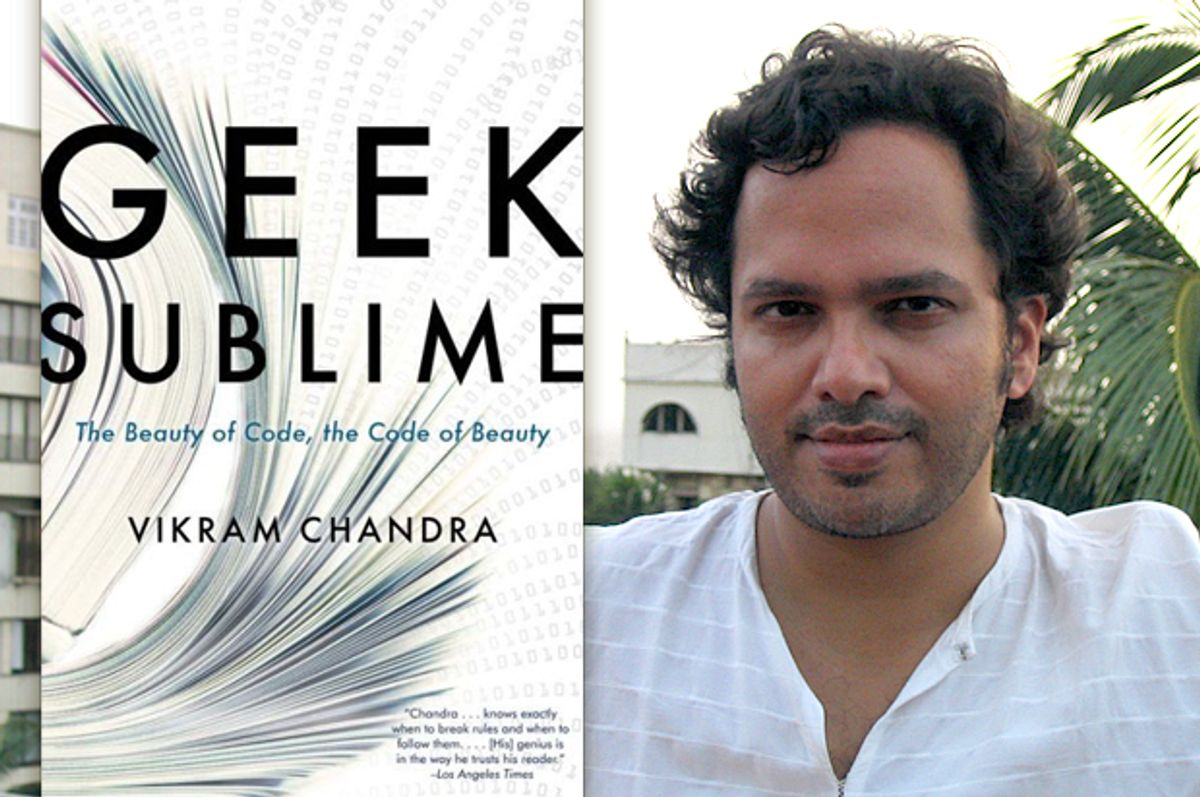

In "Geek Sublime: The Beauty of Code, the Code of Beauty," the novelist and programmer Vikram Chandra proves himself exactly that kind of multidimensional world traveler. Chandra weaves a comprehensive understanding of the history, practice and art of programming into a startling fabric that includes a fascinating dose of classical Indian philosophy and his own lifelong creative journey as a writer. Unexpected connections abound.

To pick just one typical example of his cross-discipline riffing:

At the end of a discussion (a meditation? exploration? evocation?) about something called dhvani -- the theory of "aesthetic suggestion" formulated by 9th century Indian philosopher Anandavardhana -- Chandra suddenly leaps across time and and space and quotes the American writer Flannery O'Connor:

You tell a story because a statement would be inadequate. When anybody asks what a story is about, the only proper thing is to tell him to read the story. The meaning of fiction is not abstract meaning but experienced meaning.

For a reviewer, Chandra's diversion to O'Connor is a challenge and a subtle joke about the act of reading the book itself. What is "Geek Sublime" about? Don't ask me — just read it!

Like poetry, "Geek Sublime" seems designed not to be summarized, but to be felt. As the last words of the book resonate through your brain -- "In the practice of fiction what is tasted -- first and then again -- is consciousness itself" -- you'll suddenly understand what the poet T. S. Eliot was trying to communicate when he described two years of Sanskrit study as having left him in "a state of enlightened mystification."

(Did you know, by the way, that a very strong case can be made that Sanskrit was the first programming language? Because I did not. But thanks to Chandra, I am now convinced.)

Okay, yes, my job here is do more than evoke, and honestly, it isn't that impossible a task. Because "Geek Sublime" turns out to be about a great many things. In the space of a mere 210 pages, Chandra covers broad territory. "Geek Sublime" is instantly essential to any further discussion of of whether computer code can be thought of as the same kind of exercise in creativity delivered by music or painting. (The short answer: no.) He brings keen new insight into the troubling gender divide in the American software industry. (His points about how the Indian software industry is far less male-dominated than in the U.S. crushes theories that programming is somehow intrinsically male.) Perhaps most unexpectedly, while exploring the psychology of coders and writers, he manages to integrate the vast legacy of Indian intellectual history into contemporary conversations about the meaning of art and experience. He manages to get as close to the machine as any previous literary inquisition of coding, to explain exactly how computing happens, how ones and zeroes are translated into action, while simultaneously soaring into the delicate ether of the most refined aesthetic spirituality. It is a dazzle, from beginning to end.

Who knew that Vikram Chandra -- the author of three novels, and teacher of creative writing at UC Berkeley -- was such a geek? When James Gleick (the author of "Chaos Theory" and "The Information") reviewed "Geek Sublime" for the New York Times Book Review two weeks ago, I thought the name sounded familiar. And yes, it turned out that I had devoured Chandra's sprawling, epic novel about India, "Sacred Games," seven years ago. But of the fact that Chandra had supported his early writing life by working as a programmer, I had not a clue. That he's as nimble manipulating code as he is at narrative flow was a revelation. Plenty of programmers consider themselves artists, and plenty of writers presume to declaim about programming. But very, very few can comfortably inhabit both worlds with such grace and precision.

"Fiction has been my vocation, and code my obsession," writes Chandra. What, then, to make of a nonfiction work about code and fiction? If one of the key differences between code and fiction is that code actually has to work, in the real world, as a functioning tool, to achieve its desired goal -- while fiction can be broken and shattered and not even make any obvious sense and still succeed in evoking a meaningful response -- how do we appraise a nonfictional exploration of both the fictional and real?

Does it work? Yes, absolutely. But how? Not by tripping logic gates on a silicon chip, certainly, but through something more mysterious, the chemistry of synapses and cognition.

There is so much to be fascinated by here: Like, for instance, that the structure of Sanskrit appears to have influenced the structure and development of high-level programming languages in the U.S. -- well before Indian programmers became a significant part of the American software industry.

His discussion of Indian philosophy opens up portals to a world of subtlety and sophistication that strips away Western cultural arrogance like acid dissolving a lacquered veneer. There's so much we in the West still don't have a clue about. There's so much to learn and absorb. It turns out that vast historical tidal waves -- the impact of British imperialism on India, for example -- inform to this day how Indian and white programmers interact with each other in the cubicle farms of Silicon Valley.

Across thousands of years of history, from the India of his youth to the United States of his professional career, down deep in the nitty gritty of compilers and assembly language and object-oriented programming, "Geek Sublime" tells one coherent story about the creative process and our aesthetic reactions to art. There may be times when the newcomer to Indian philosophy can get a little lost in the intricacies of viyabhicaribhavas ("fleeting emotional states") and samskaras and vasanas ("latent impressions") but sometimes poetry can be inscrutable and still pack a payoff.

And then there's rasa, a word that, Chandra writes, "literally means 'taste' or 'juice'" -- but in the context of classical Indian discourse is defined as "the aestheticized satisfaction or 'sentiment' of tasting artificially induced emotions."

Chandra is all about the rasa. Because that's what artists do, right? And that's why writers write, isn't it? We want you to feel the rasa. We will artificially induce your emotions and you will love us for it.

The chief dialectician of rasa, Abhinavagupta, the 10th century mystic, aesthetician, musician, poet, dramatist, theologist and logician who is considered one of India's greatest philosophers (and of whom I knew zilch about before reading "Geek Sublime") comes off, through Chandra's telling, as a pretty smart guy.

Chandra writes:

Abhinavagupta tells us that his teacher said, "Rasa is delight, delight is the drama; and the drama is the Veda," the goal of wisdom.

"Geek Sublime" is a wise book.

Shares