"Down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean," Raymond Chandler wrote in "The Simple Art of Murder," which could be called the manifesto of the American hard-boiled detective novel. This man, the detective, "is neither tarnished nor afraid. ... He is the hero, he is everything. He must be a complete man and a common man and yet an unusual man. He must be, to use a rather weathered phrase, a man of honor, by instinct, by inevitability, without thought of it and certainly without saying it."

It's a worthy aesthetic, and Chandler was certainly the master of it, even back in 1944, when he wrote "The Simple Art of Murder." The essay was a repudiation of the English school of murder mystery -- best represented by Agatha Christie -- or, more specifically, the countless American knockoffs thereof, genteel, stilted puzzles set in "Miami hotels and Cape Cod summer colonies," rather than manor houses. Chandler held up Dashiell Hammett as the exemplar of what he referred to as the new "realist" school of crime fiction, yet Chandler was Hammett's equal, if not his superior in the style that would also become known as noir.

Still, every genre gets tired after too much repetition; take the western, which (although Chandler doesn't acknowledge as much) provided the pattern for the hard-boiled detective novel. I may not ever get bored with Chandler, but too often lately, I've picked up a much-praised new crime novel to read about some tough, tough guy, usually in a car, with a gun. Pretty soon will be more guns, some fistfights, assorted criminals exchanging snarling threats of various degrees of scariness and wit.

If the hero is police, then he'll be the departmental maverick, too honest and decent to engage in office politics yet laser-focused on nailing his perp. Often there's a murdered relative, almost always female, to juice this crusader's motivation. His marriage will have fallen apart because he's too stoic and too devoted to the Job to sustain a real relationship. But he'll be devoted to his kid and a one-woman romantic at heart, even if hardly anybody ever gets near that heart. He'll brood a lot and go home alone. He'll have a temper, but a righteous one. He might drink too much or be too ready with his fists, but that just makes him a bit of antihero, that familiar figure from cable TV dramas. And he won't even necessarily be American; the Norwegian novelist Jo Nesbo's Harry Hole might have been ordered up from whatever factory cranks out these guys.

It's all getting awfully predictable, which may explain why this reader can't bear to finish yet another novel about such a hero. I've found instead that the crime novels I open with the keenest anticipation these days are almost always by women. These are books that trespass the established boundaries of their genre, adding a dash -- or more than a dash -- of fabulism, or lingering over characters who used to serve as the mere furniture of the old-style hard-boiled fiction. They may dare not to offer a solution to every mystery or to have their sleuths arrive at those solutions by nonrational means. Their prose ranges from the matter-of-fact to the intoxicating, and the battlefields they depict are not the sleazy nightclubs, back alleys, diners and shabby offices of the archetypal P.I. novel, but a far more intimate and treacherous terrain: family, marriage, friendship.

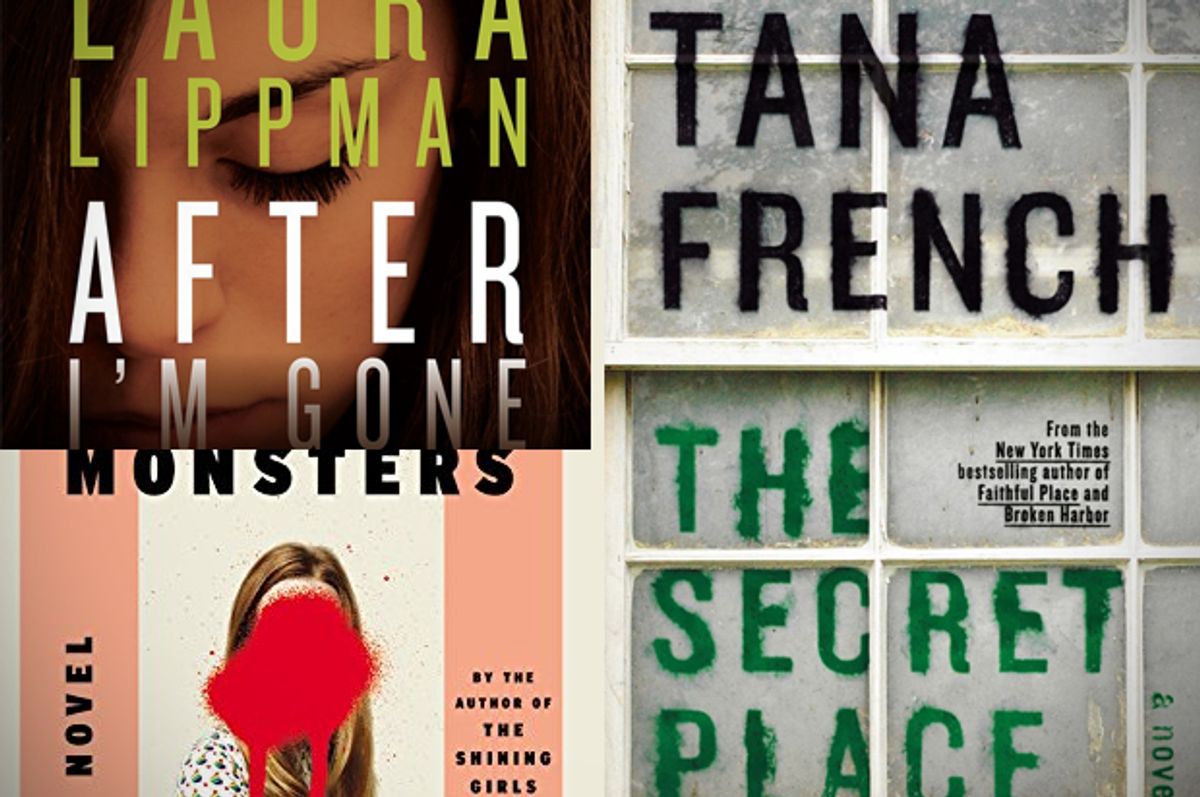

Gillian Flynn, the author of "Gone Girl," is only the best-known of these writers. Other stars include Kate Atkinson, Laura Lippman and Sara Gran, plus two authors who have brand-new novels out this month: Tana French and Lauren Beukes. What they do isn't utterly new. These novelists are the heirs of writers like Patricia Highsmith and Ruth Rendell. The crime fiction expert Sarah Weinman has identified a subgenre she calls "domestic suspense" and recently published an anthology, "Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives," whose earliest examples date back to the 1940s.

When Chandler wrote "The Simple Art of Murder," he objected to the English (or "cozy") mysteries as "too contrived, and too little aware of what goes on in the world." Those stories were about murders that happened simply for the sake of creating a mystery. The hard-boiled detective novelists, by contrast, wrote about "the kind of murders that happen" depicted with "the authentic flavor of life as it is lived." No doubt they did (Hammett had worked as Pinkerton agent), and perhaps today's versions do, too. "That's how life really is," is often the defense of brutal machismo in fiction. But how would I -- or, for that matter, you -- know? Like most readers of crime fiction, I don't hang out with criminals or policemen, have never met a gangster or a hit man or a gunsel or a drug runner. My experience with crime is strictly as a victim (burglary, armed robbery, etc.), and fleeting.

Yet every crime erupts from an emotional situation, even if the emotion in question is mere greed. The crime writers I've come to admire most mine the distorted relationships that produce and follow crime for their material; this is one vein of realism that has gone largely untapped and overlooked.

In addition to her Tess Monaghan series, about a Baltimore P.I., Lippman has been writing a series of stand-alone novels about women connected in various ways to male criminals. "I'd Know You Anywhere" is the story of a suburban matron who harbors the secret that she is the only surviving victim of a serial abductor and murderer of women; he wants her testimony to save him from execution. In "And When She Was Good," a similarly respectable woman is the discreet proprietor of an escort service and coping with the eminent release from prison of the violent pimp who turned her out. (He's also the father of her son.) Most recently, Lippman's "After I'm Gone," is a masterful ensemble piece teeming with vital, distinctive characters all connected to a Jewish numbers runner who skips out to avoid prison, leaving a wife, three daughters and a stripper mistress behind.

If this new, genre-crossing breed of female crime writers has a shared quality, it's their focus on the penumbra of crime, a truer portrait of the halo of human damage surrounding violence and death. Atkinson's detective hero, Jackson Brodie, may be a wandering knight rather like Chandler's "man of honor," albeit less jaded. But the other characters in each of Atkinson's four Brodie books command their own point-of-view chapters and are as idiosyncratic and as sharply drawn as the sort of people you'd meet in a literary comedy of manners. Sara Gran's Claire DeWitt is hard-bitten and wisecracking in the conventional noir P.I. mode, but her methods involve such unconventional techniques as lucid dreaming and drug-induced visions. A disciple of a cryptic French detective whose treatise on the subject has a tendency to materialize when most needed, she is the private eye as reimagined by Borges.

French may be my favorite of the bunch, a novelist whose every novel surprises, expanding into new subject matter and storytelling modes. Beginning with 2007's "In the Woods," she has brought a fully fledged literary sensibility to the cases of the (fictional) Dublin Murder Squad. Each novel is narrated by a different detective, and each describes the one case that cracked him or her open. It's a strategy that provides some continuity (a minor character from one novel becomes the central character in a later one) without the soap-opera-fication that afflicts the detectives in long-standing series, whose lives become a preposterous series of high-stakes crises. A thin vein of the uncanny runs through most of French's novels: mysteries that go unsolved, premises that flirt with impossibility, paranormal occurrences that may or may not be imagined.

In French's most recent novel, "The Secret Place," she alternates the first-person narrative of Stephen Moran, a young detective who has been relegated to Cold Cases but longs for a shot at the Murder Squad, with third-person flashbacks told from the perspectives of four extraordinary 16-year-old girls in a private Catholic boarding school. Moran, who has earned the mistrust of some higher-ups, finds cause to reopen the investigation of the year-old murder of a boy from a neighboring school; his body was found on the grounds of St. Kilda's. To work the case, however, he needs to win the trust of a well-armored homicide detective -- female, working-class, mixed-race -- who is herself an outcast from the rest of the Squad.

French's stories often have an underpinning of myth or fairy tale. In "The Secret Place," it's the Greek legend of the Maenads, Dionysus' wild, purportedly invincible female disciples. The four friends sneak out of the dorm at night to visit a grove in the woods. They promise each other not to "go near any guy, ever, till college." Their loyalty to each other, combined with this refusal to participate in the self-hating rat race of adolescent girlhood, gives them access to a remarkable power, social and perhaps something more. In Moran, they inspire longings for the friendships he has had to sacrifice in his quest to leave behind his lumpen proletariat origins. The cost of class mobility is one of French's favorite themes; "Broken Harbor," published in 2012, traces the disintegration of a family stranded in one of Dublin's deserted pre-recession housing developments, a modern-day ghost town, figuratively -- and perhaps literally -- haunted.

Chandler wrote that his hero was a "lonely man" and that the author did "not care much about his private life." As a rule, he barely has one. A descendant of the lone gunslinger or embattled frontier sheriff, the hardboiled P.I. is a solitary, wandering soul, roving from mansions to dives in search of the truth. Like the western, the traditional noir detective story is preoccupied with how a hero can be constituted in a corrupt world. Usually it's by holding himself apart from others. John Wayne's character in "The Searchers" values and defends what he sees as the moral, domestic lives of white settlers, but he has encountered too much barbarism beyond civilization's edges to enjoy such a life himself. He's damaged, which pretty much lets him off the hook for the sticky work of actually connecting to and accommodating another human being, while still allowing him to feel sorry for himself.

Detective fiction has long allowed writers to explore social landscapes; a sleuth can poke his nose into all sorts of places it doesn't belong, offering his readers a vicarious voyeurism. Lauren Beukes' "Broken Monsters" is about contemporary Detroit -- the homeless scavenging in derelict neighborhoods, the hipster artists seeking cheap rent and "ruin porn," the remnants of the city's civil service struggling to do their jobs without functional computers -- in the same way her previous novel, The Shining Girls," was about Chicago. Beukes' police detective is a single mother, but the detective's teenage daughter (who amuses herself baiting creepy guys on the Internet with her best friend), is just as crucial to the story. So is TK, who works at a soup kitchen; JoJo, a washed up journalist look to revive his career on YouTube and a befuddled middle-aged artist whose mind has been invaded by a entity who represents the very worst of the artistic impulse.

Beukes, whose roots are in science fiction, delivers the most surreal crime narratives of this bunch. "Broken Monsters," like "The Shining Girls," is a serial killer thriller, but as Beukes reimagines that genre, the killer is literally inhuman, demonic. In "The Shining Girls" it is an evil force that feeds off the wasted potential of the promising young women it destroys. In "Broken Monsters," a novel of bleeding-edge references (the Russian Mutant, anyone?) and preoccupations (boys recording their abuse of passed-out girls on their smartphones), the killer is a frustrated creator seeking a fast lane into as many minds as possible. This is a trippy scenario, and Beukes is also the most adventurous stylist among these writers, dotting her potboiler plot with Joycean streams of consciousness and transcripts ripped from Internet comments threads. But as with "The Secret Place," her novel is about connection, loyalty, the battered community of Detroit and what still holds it, ever so precariously, together.

Neither "The Secret Place" nor "Broken Monsters" has a hero, let alone a lone, brooding one. Far from repudiating the palace intrigues of the Dublin P.D., Stephen Moran seeks to negotiate and ultimately master them. The corrective to wickedness in both novels is not a bruised, melancholy individualism, but connection, loyalty, trust. And what all of these novels assert, over and over again, is that wounded people can do just that. It's not just the streets that are mean. Women and girls are more familiar with the business end of the human capacity for cruelty and evil than Chandler's old-fashioned man of honor would ever suspect; so many become acquainted with it at a tender age. But they are also tougher and more dangerous than he'd suspect as well. Tough enough to recognize that walking down those mean streets alone is the coward's way out. Far greater challenges await within.

Shares