It’s often said that writing about traumatic events can be therapeutic. Perhaps. Writers are not especially known for the calm, limpid depths of their solace. For myself, I can say only that the long, strange process of writing "Epilogue" — a memoir in part of my mother, younger brother and father — showed me something about the ways in which we use storytelling — or try to use it, anyway — to comprehend the fractured, misshapen forms taken on by grief and loss.

My mother died when I was 17 — a brain tumor that spread, chewing up both her body and her mind over eight excruciating months. When someone dies slowly, you write them out of your life. You celebrate and comfort them the best you can, but you are always preparing, strengthening yourself as they wither, so that you’ll no longer need them when the moment finally comes. It’s a cruel series of revisions. Illness can turn the parent into the helpless ward and the child into the uncertain protector, and the reversal brings with it a dense tangle of confusion, hurt and guilt. But, as a narrative line, illness is at least straightforward. There’s a clear beginning, middle and end — the afflicted either gets better or they don’t.

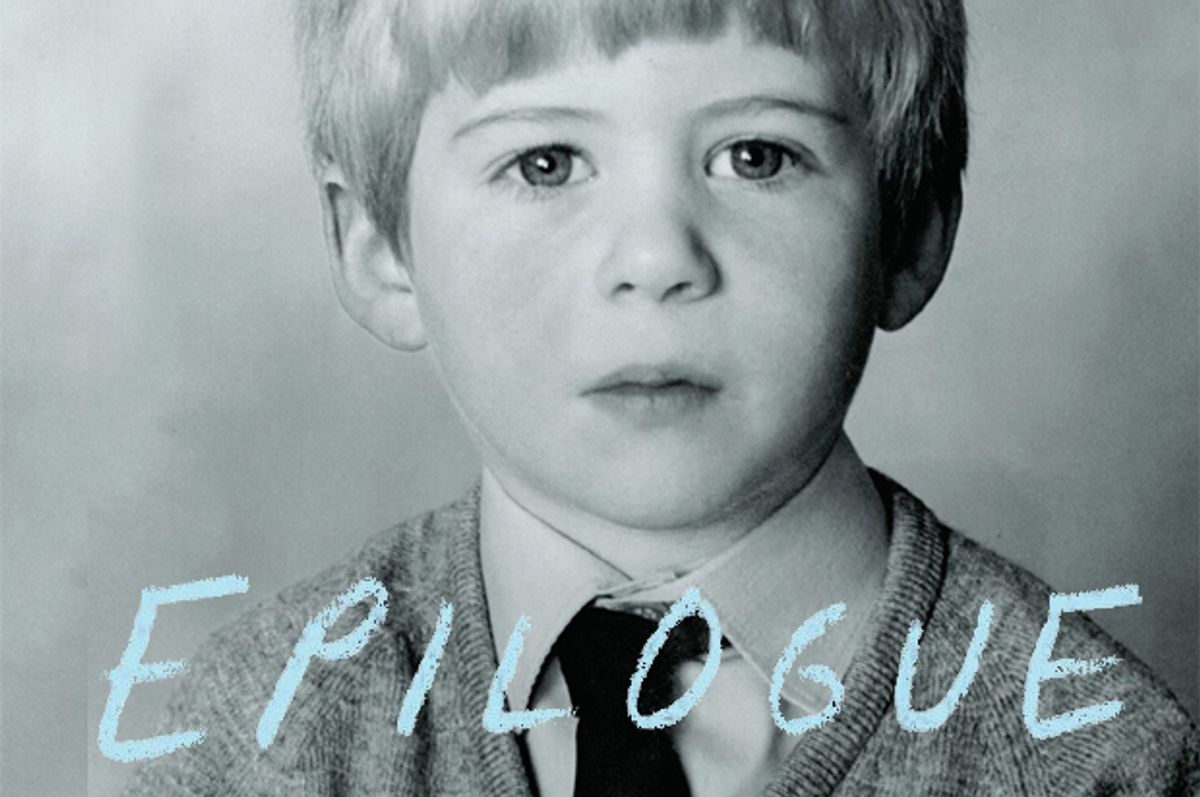

When someone close to you dies suddenly, however, the story has a different shape. Or rather it has no shape at all. The line of his life is simply broken off, an abrupt dead end. I was 19 when a freak car accident killed my younger brother, Rory. It seemed impossible that he would be taken so prematurely; the story logic was all wrong. He was 18, just graduated from high school, with the vast canvas of his future unfurling before him. The accident killed him instantly, hurling him, for my father and me, into a netherland somewhere between reality and the haunted imagination.

At the funeral there was no body to see, just a closed casket that sat up front, mute as a hyphen. He was gone, utterly gone, but there was no physical evidence of his passing. So he lingered. For months, my dad and I kept waiting for Rory to just walk through the front door. His presence was everywhere, the subtext of almost everything we said to each other, but he never showed himself. Over the last 17 years, I have dreamt very little about my mother. Rory, on the other hand, has visited me often, no more so than seven years ago, when I first started the novel that would eventually evolve into "Epilogue."

It was a strange creature, that novel. It concerned characters so like my mother, father and brother that I saw no need to change their names. I didn’t just re-create scenes from memory; I also tried to explore moments for which I had not been present, hoping to illuminate the dark corners of a family story shrouded with secrecy and silence. It was as if I was using my family as test specimens, maneuvering them into new, revealing scenarios to see what they would do and why they would do it.

There were, in the end, practical, literary reasons why this odd hybrid of fiction and nonfiction didn’t work. It was too convoluted and too stuffed with incident. (Strange that life often permits more coincidence and mayhem than fiction will allow. “If you put all of that in your novel,” a friend once said about my early manuscript, “no one will believe it.”) But more than that, the process of trying to almost literally embody my family on the page was unhinging me. As I wrote about Rory, I also dreamed about him feverishly. Some mornings I woke, sweating, my heart whomping like a punch bag, and saw him standing in the corner of the room, mere feet away. I reached out for him, still caught somewhere between the real world and my interior world, the world I was laboring to re-create on the page. But in those few waking, startled instants, he slipped away, dissolved into dust motes hanging in the air, lit up and dancing in the early morning sun.

I was trying to use the novel form to finish my brother’s story. I was trying to give him a proper ending, trying to undo the accident’s cruel interruption. Instead, it was undoing me. The only way to write about Rory was to do so directly; it was time to come back to this world. I had, finally, to let my brother’s story line hit its dead end.

As harrowing as it was to bring my mom and Rory to the page, the most difficult parts of "Epilogue" to write, on a purely technical level, were about my father. His was a story twisted and blurred by addiction. (And further complicated by the secrets he held, though that’s another matter altogether.) Because he often hid his drinking, it’s difficult for me to say whether my father was a full-blown alcoholic or a “problem drinker.” Either way, drink was his cure for grief, and he needed stronger and stronger doses as the years wore on.

As a character, he became wildly unpredictable. One night he would be smiles, laughter and happy industry as we set about making ourselves a big French dinner. The next he would be so drunk he could only stalk the house in a stupor. He would break unexpectedly into tears or fall into sullen, silent rages. Is a person’s true self revealed or obscured by addiction? Whichever way, my dad became both antagonist and victim. In the slow, uncertain composition of "Epilogue," as in life, I never knew whether to hate or forgive him for those Seagram’s Canadian bottles that piled up in the garbage. I never knew whether to blame the drink or the drinker or, indeed, myself for not somehow putting an end to it. He died an alcoholic’s death, a perforated ulcer, when I was 24.

Writing about my father was an agonizing process, full of second guesses and constant doubling back to try to explain, to myself as much as the reader, the contradictions our lives could never quite contain. A family’s story is a ragged patchwork, all crazy patterns and loose, fraying threads. One of the hardest things to learn is how to keep from trying to tie those threads off.

As I read all of this back, I find myself emphasizing the difficulty, the labor of writing "Epilogue." But at times it was a joy, no more so than when I dwelled so long and so closely with my family as characters that I really did feel they were there in the room with me. A story about loss can be an act of resurrection. And even if the miracle doesn’t last any longer than it takes to finish a paragraph or a sentence, there is still that moment, that suspension, when life and death and time are held for a moment, hanging like those dust motes trembling in the sunlight.

And then you turn the page.

Shares