I suppose nearly everyone who sees the unclassifiable and often spectacular film “20,000 Days on Earth” will assume that Australian-born singer-songwriter Nick Cave, the poet laureate of the post-punk generation, is both its subject and its uncredited co-author. There’s clearly a level on which that is true: British visual artists and video makers Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard, the eccentric and thoroughly charming couple who made the film, could never have done so without Cave’s collaboration. It’s not a biography nor is it anything like a standard music documentary – indeed, I’m not sure it can be considered a documentary at all, at least not all the way through. But “20,000 Days” offers an exceptionally intimate portrait of an artist who has sometimes sought to resist explication.

In one sequence, which is literally a fictionalized therapy session with an actor playing a shrink, Cave discusses his first sexual experience (which, not surprisingly, he recalls in aesthetic or cinematic terms), his loving relationship with his father (who died when he was 19), and his parental anxiety that his twin sons are having too sheltered and privileged an upbringing, as the suburban English children of a rock star. He remembers, he says, a quite different childhood: playing chicken with oncoming trains on a railroad bridge near his Australian hometown, and cheating death by jumping into the river below. Doesn’t that anecdote explain nearly everything about Cave’s worldview, and the mythological universe he creates? Nick Cave really did grow up in a Nick Cave song!

During an impromptu press conference after the film’s premiere at Sundance last winter, someone asked Cave whether it should be considered fiction, documentary or psychodrama. He responded to the last word: “That. Psychodrama, except without the ‘drama’ bit.” My personal feeling is that while Cave’s artistic fingerprints are all over this movie, his influence over it is essentially indirect or at a distance. He met with Forsyth and Pollard – a middle-aged, hobbit-flavored couple who, when I met them, were dressed head-to-toe in black Goth apparel – decided they were talented and strange and that they clearly loved his work, and decided to let them at it. Maybe they didn’t exactly make the Nick Cave movie he would have made, but they damn sure didn’t make one that anyone else would make either. For the most part, “20,000 Days on Earth” – the approximate amount of time Cave has been alive on this planet – is an imagistic and impressionistic work, a Nick Cave-esque tone poem driven by moments of visual and thematic juxtaposition you either have to reject or accept.

To be fair, sometimes Forsyth and Pollard draw near a much more familiar documentary mode. We see Cave and his band, the Bad Seeds, recording their 2013 album “Push the Sky Away” – including a number involving a chorus of French schoolchildren -- and Cave and longtime bandmate Warren Ellis lunching on home-cooked pasta and eel and reminiscing about long-ago gigs. (Ellis is an impressive musician who can play violin, piano, guitar, bouzouki and numerous other instruments, and appears to be no slouch in the kitchen as well.) The story they dredge up about opening for Nina Simone at an outdoor concert in London, which culminates with the phrase “Champagne, cocaine and sausages,” is especially delightful, and also enlightening. There are prose-poem passages drawn from Cave’s “weather diary,” documenting the changing skies over Brighton, his rain-sodden adopted hometown on the south coast of England. There are archival images of Cave’s famously nihilistic early band the Birthday Party, accompanied by hilariously dry narration from the man himself.

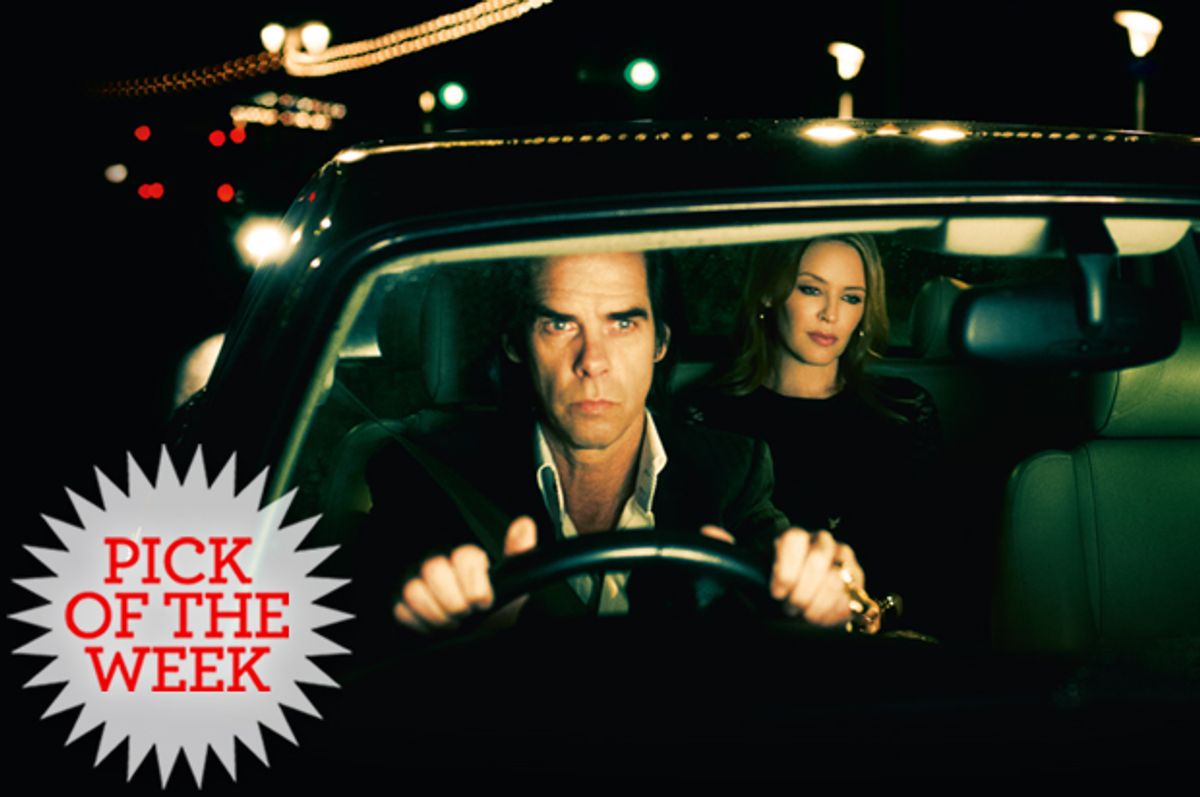

Somewhat more mysteriously, there is also a set of engineered conversations, each one staged in a moving car, between Cave and an old friend or former musical comrade. Actor Ray Winstone discusses his humble origins in the East End of London and his early interest in Shakespeare, and is certainly a compelling presence, although his connection to Cave is not entirely clear. Guitarist and noise-rock pioneer Blixa Bargeld, who founded the legendary German group Einstürzende Neubaten and spent 20 years as a member of the Bad Seeds, shows up to talk about the currents of pop history that brought him and Cave together and then drove them apart. At the other end of the cultural continuum comes pop chanteuse Kylie Minogue, who turns out to be a thoughtful and considerate person in real life. (And why not?) It was Minogue’s presence that helped engineer Cave’s one and only trip to the top of the charts, with their 1995 duet single “Where the Wild Roses Grow.” As Cave quips, many radio listeners bought the ensuing album (it was “Murder Ballads”) and immediately decided never to have anything to do with him or his band again.

Forsyth and Pollard have said that “20,000 Days on Earth” was inspired by several flawed and ambitious non-narrative films of the ‘60s and ‘70s, including Jean-Luc Godard’s Rolling Stones documentary “One Plus One” (aka "Sympathy for the Devil"), the loopy and half-fictionalized Led Zeppelin concert film “The Song Remains the Same” and Lindsay Anderson’s deranged allegorical fantasy “O Lucky Man!” So that’s the world we’re in here, and if you’re impatient with a certain amount of willful artistic randomness, this might not be the movie for you. I have to admit my maximal bias here: I think “20,000 Days on Earth” is a beautiful film, if also more than a little bit cracked, but I would not be the person to tell you how it plays to non-Cave fans. I don’t think this is only a movie for hardcore devotees of the post-punk Dylan, on the other hand; it’s an affectionate but faintly self-mocking portrait of a guy who knows that he skirts the edge of pretentiousness almost all the time. (Cave seems to enjoy it when Ellis compares him – compares his sound, that is -- with Lionel Richie.)

One thing “20,000 Days on Earth” shares with those artistic predecessors of earlier decades, beyond a repeated willingness to violate the so-called boundaries between truth and fiction, is an evident passion and enthusiasm for the subject matter. You can feel the trust between Cave and the filmmakers, as when he discusses the years he lost to heroin addiction or his fears of losing his memory as he grows older. He has spent his life creating a world in his songs, he tells the therapist — an absurd and violent world of heroes, villains and doomed romance in which God is not only real but an Old Testament presence, watching over everyone and keeping score. In the outside world, the real world, Cave does not believe in God. But this dense, puzzling and often gorgeous film —itself something like a melancholy and doom-haunted Nick Cave song, or like a delicious chocolate with live insects at the center — reminds us that God and reality and music and stories and the world are all things we make up to console ourselves along the mysterious road from birth to death.

”20,000 Days on Earth” is now playing at Film Forum in New York. It opens Sept. 26 in Boston, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, San Francisco and Seattle; Oct. 3 in Dallas, Denver, Grand Rapids, Houston, Kansas City, Missoula, Mont., Pittsburgh, Salt Lake City, San Antonio, Washington, Austin, Texas, and Columbus, Ohio; Oct. 10 in Kalamazoo, Mich., New Orleans, Omaha, Tucson, Ariz., and Lubbock, Texas; Oct. 17 in Miami, Monterey, Calif., Portland, Ore., and Tulsa, Okla.; and Oct. 24 in Detroit, Phoenix and Santa Fe, N.M., with more cities and home video to follow.

Shares