It took more than a dozen years for Denzel Washington to reunite with Antoine Fuqua, the director who pushed him into startling new territory as the dirty-cop antihero of “Training Day.” Neither man, one could argue, has been quite the same since. Washington remains an A-list star, but has made a series of largely forgettable action vehicles and inspirational sagas; his best two roles of the last decade have come in Spike Lee’s “Inside Man” and Robert Zemeckis’ “Flight,” but only the first of those stands up to more than one viewing. Fuqua is a master manipulator of style and atmosphere who has often chosen (or gotten stuck with) mediocre material or worse: I have a soft spot for his back-to-basics cop opera “Brooklyn’s Finest,” but his best movie since “Training Day” is probably “Shooter,” with Mark Wahlberg. (I had totally forgotten that Fuqua directed a King Arthur film starring Clive Owen, and there’s a reason for that.)

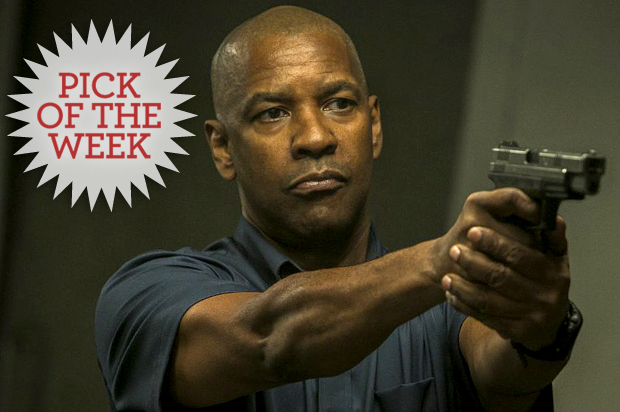

Now the Washington-Fuqua duo is back together for “The Equalizer,” a synthetic blend of sentimental fantasy and Nietzschean supercop-revenge saga based on the all-but-forgotten 1980s TV series with British star Edward Woodward. This is an entirely different kind of movie than “Training Day,” and far less ambitious in narrative terms, but it’s a triumph in its own brooding, ultraviolent and faux-meaningful fashion. If that sounds like I’m recommending “The Equalizer” and then trying to take it back, that’s exactly right. It’s not quite that I think this movie is a guilty pleasure, since “pleasure” is hardly the applicable term. “The Equalizer” is gripping, mysterious and even sometimes moving, but it’s never pleasant, still less fun. If you decide to go, don’t claim you weren’t warned. If you skip it, you’re missing one of the year’s signal works of superior Hollywood craftsmanship.

Fuqua builds considerable suspense from the near-silent opening scenes onward, and then delivers a series of grotesque and imaginative killings, all in entirely formulaic fashion. What isn’t formulaic is the persistent David Fincher mood of nightmare – the sense that we’re in an imaginary universe related to our own, but not quite the same – and the iconic stillness and loneliness of Denzel Washington. Every director who’s ever worked with Washington, black or white, has taken advantage of his unusual combination of good looks and inwardness, his slightly standoffish demeanor, that sense that he’s carrying things around that we should not presume to try to understand. It might be a cliché to suggest that an African-American filmmaker like Fuqua sees the star’s visage in a different light, but there’s no question that in their two movies together Fuqua has homed in on Washington’s face with a ruthless intensity. (Both “The Equalizer” and “Training Day” were shot by master cinematographer Mauro Fiore.)

Washington will turn 60 later this year, and Fuqua makes him look grayer and older than ever before, subtly but noticeably diminished in scale from the superstar of 15 or 20 year ago. His character, Robert McCall, lives alone, dresses in conservative American-guy drag – button-down shirts and relaxed-fit slacks – and spends his workdays pushing a dolly around inside a Home Depot-like big-box store in Boston. (Only Washington could look this good, at this age, in a wardrobe purchased off the rack at J.C. Penney.) But we can tell that something about the guy doesn’t fit. Well, OK, we can tell that because we showed up to see an action movie called “The Equalizer,” which for almost half an hour has no action in it whatever. Robert barely sleeps and spends his nights at a 24-hour diner, drinking tea, working his way through a list of classic literature and making small talk with a Russian hooker who calls herself Teri, or sometimes Ilena (Chloë Grace Moretz). When we first meet him he’s reading “The Old Man and the Sea,” and by the end of the film he’s gone through “Don Quixote” to “Invisible Man,” and I suppose those function as narrative cues.

Honestly, I’d have been just fine if “The Equalizer” never abandoned its brooding, late-night Wong Kar-wai-does-Edward Hopper mode. Then it would be some other kind of movie and not this one, where Teri/Ilena’s overly tattooed and ludicrously coiffed pimp (David Meunier) finally runs afoul of McCall by roughing her up one too many times. McCall actually shows up with cash to buy Ilena from her captors, only to be ridiculed in Russian (which of course he understands), and you probably understand how that scene ends. Beneath McCall’s mild, tragic lumber-guy surface there beats, of course, the heart of a ninja super-spy assassin, not so secretly yearning to kick Russkie tail (and drive household implements into Russkie eyeballs). Neither Fuqua nor screenwriter Richard Wenk could have predicted an old-school international crisis in 2014 that pits Russia and America against each other, presumably, but it’s fair to say that “The Equalizer” captures a mood of Cold War redux that was already in the air.

It’s certainly possible to read too much into this film’s racial politics; the fact that McCall is black is mentioned only once, pretty much in passing (the character was white in the TV show). But Washington’s color has never been irrelevant in his career, and the specifics of this particular jingoistic fantasy – a semi-retired black man in dad clothes, taking down the bling-laden, Uzi-toting metrosexual meatheads of the Russian mob all by himself – are rife with psychoanalytic potential. McCall is like a vision of classic American manhood, telegraphed from the past and translated into a multicultural idiom. He knows his way around lumber, power tools, firearms and superhero-grade martial arts, and if you put your hands on a woman he will make you pay, by gum. He’s like the single-handed cure for everything that’s wrong with America, from the international hatred and humiliation to the “crisis of masculinity” to the racial incomprehension to the confusion about the scale and consequences of violence against women. That cure is some kind of government-trained human killing machine, of course, and so in objective terms not all that reassuring. But hey, a hero’s gotta come from somewhere.

So the general tone of “The Equalizer” is already pretty weird even before veteran movie villain Marton Csokas shows up in the nemesis role of Teddy, an ex-KGB psychopath who resembles an evil version of James Bond from that alternate universe where Mr. Spock has a goatee. He has an unplaceable accent, a Savile Row wardrobe and even scarier tattoos than the regular Russian criminals, and he and his band of hirsute malefactors have a final showdown with McCall, inside the non-Home Depot store, that ranks among the grandest set-pieces in recent action-movie history. All of this takes place in a corrupt and enslaved version of Boston, and America, that appears to have been sucked dry of color and life by giant vampires; it’s partly the city where Neo works in “The Matrix” and partly the Gotham of the “Dark Knight” series.

I don’t know how far into late middle age Washington wants to pursue this character, or whether the dark magic that makes this mendacious and parasitical film appear to thrum with subterranean meaning can be repeated. There’s clearly potential for a franchise here, but one assumes it’ll be a franchise based on the lethal use of kitchen implements and retail hardware, not on the surreal loneliness of its main character. But that’s where the moral and psychological truth of “The Equalizer” lies: not in the infantile fantasy payback that will restore America’s global dominance and reassert the imaginary urban order of 40 or 50 or 60 years ago, but in a man sitting alone with an old book, as a haunting old song plays from somewhere and the world around him fades into night, into nothing.