“Ebola.”

It’s on everyone’s lips in the media, in the medical establishment, in communities around the world. The public is learning more every day about its nature as a virus and as a public health contagion. Doctors and researchers are working with extreme urgency to get out ahead of it.

But perhaps because the disease is so overwhelming – the symptoms, the mortality rate, the social horror it precipitates, the prospect of vast human devastation – we have a strange collective blind-spot about the term itself: Where exactly does the name come from? What does it mean?

English professor to the rescue!

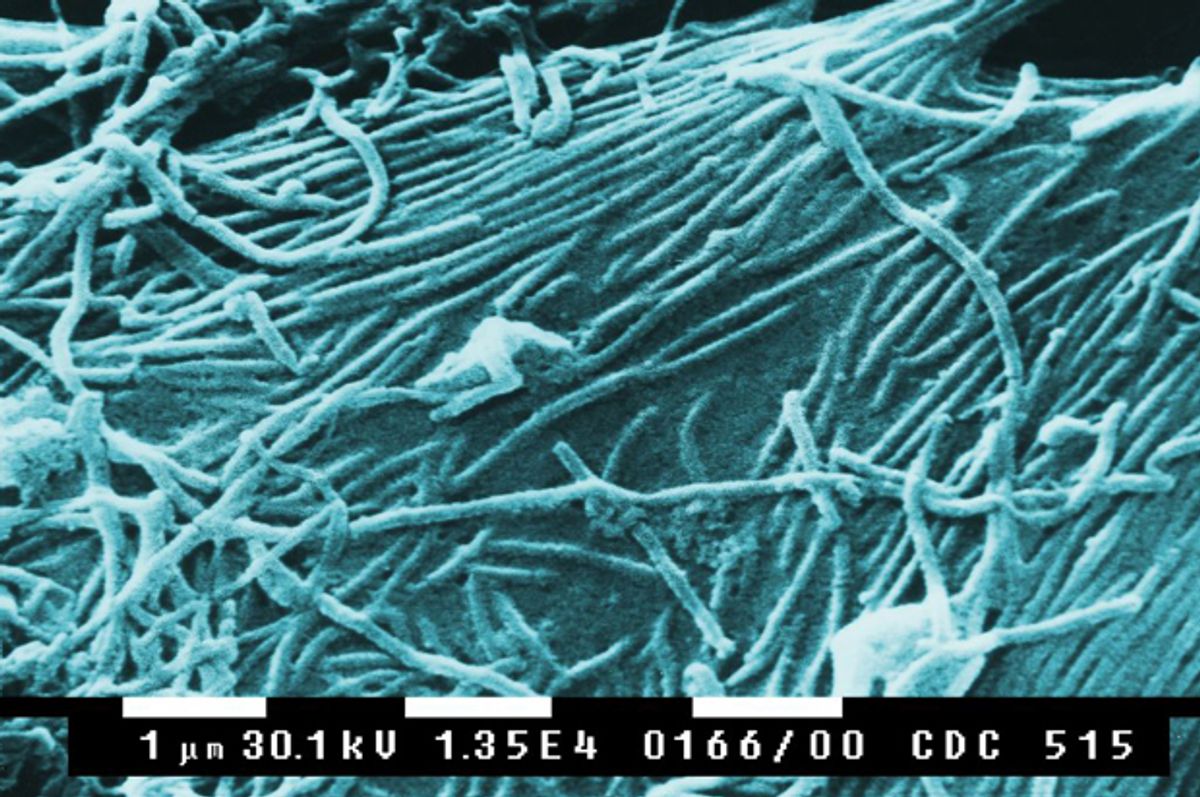

The connotations of Ebola are graphic, grisly, disheartening. The images we associate with the word are grotesquely incontinent, nearly alien bodies in the throes of a violent death; or the hazmat suits, worn by the few available healthcare providers, looking as though they’re designed for Chernobyl, or outer space.

The visuals convey fear: Stay far away, and pray that this horror doesn’t come anywhere near us. Maps depict no-go zones, quarantine sectors, proximate areas at risk. There has been some degree of sympathy for those who suffer the disease, and this has translated into somewhat significant levels of material support to treat victims, ease their suffering and halt the spread -- but only recently. Dr. Kent Brantly, the American doctor who contracted (and was subsequently cured of) Ebola, himself noted that the world’s attention for the plight of Africans was relatively minimal, and slow in developing, until two white people came down with it. In the minds of non-Africans -- and to our great discredit -- the disease seems to be construed largely as exotic, as foreign, as defined primarily by its "other"-ness.

Looking at Ebola as something explicitly distant may provide people a sense of protective safety from this deadly disease. President Obama, after visiting the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention earlier this week, said that while it was crucial for the United States to help contain Ebola, the chances of it spreading here are “extremely low.” A White House fact sheet announces: “U.S. health professionals agree it is highly unlikely that we would experience an Ebola outbreak here in the United States, given our robust health care infrastructure and rapid response capabilities.” The subtext is that this is not our problem.

“Ebola.”

What are we saying, and hearing, when we invoke this term? It’s interesting to think about where names and words come from, and their meanings “mutate” (as the virus itself, in a worst-case scenario, might also mutate into something that is transmittable even more robustly than it is now). I don’t mean to distract attention from the human tragedy taking place, but it’s interesting to think about how the language we use frames our experience of this contagion.

In 1976, two outbreaks of this ravaging viral disease that had never been seen before were recorded in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) and Sudan. The Zaire outbreak took place at Yambuku, an isolated village deep in the rain forest, in the north of the country near the Ebola River, a small and winding tributary of the Congo River. About 600 people were infected altogether, with a mortality rate reaching as high as 90 percent.

There have been about a dozen subsequent eruptions of Ebola. Half of them led to a few hundred deaths each, while the others were smaller in scope. Now, the largest outbreak ever seen is growing exponentially, catastrophically. Some forecast that hundreds of thousands of people might catch the virus before it is brought under control, which could take over a year. The area of vulnerability has expanded greatly across West Africa: Liberia will likely suffer an enormous toll as the virus rages through densely populated urban areas. Guinea and Sierra Leone continue to be battered, and Nigeria and Senegal are starting to see cases as well.

I think most people are unaware that the name given to the virus specifically refers to the Ebola River, which seems to be a fairly obscure landmark, at least as far as the Internet is concerned: Besides its location and the fact that it lent its name to this illness, Google has virtually nothing to say about the river.

But whether or not we are aware of the Ebola River, the name nevertheless sounds recognizably African, with its long vowels and crisp, hard rhythmic consonants. In meter, Ebola is an “amphibrach.” Less common to students of English poetry than dactyls, iambs, trochees and anapests, an amphibrach is a word with a stressed syllable sandwiched between two unstressed syllables. English words like “persistent” and “together” have this pattern. African (and African-origin) words and names are more commonly amphibrachic: “Uganda,” “injera,” “banana,” “impala,” “kalimba,” “macaque,” “merengue.”

“Mandela” is an amphibrach, and so too – to the delight of racists and conspiracy theorists – is “Obama.” Our president’s name is a close sound-match to Ebola: both the same meter, and five letters long (three of which are vowels and three of which appear also in “Ebola”).

Names of diseases may or may not accurately reflect their nature, but they certainly indicate something about how people think about them. Colloquial names for medical conditions are often eponymous: sometimes commemorating the scientist who discovered the condition (Alzheimer’s, Marfan syndrome, Bell’s palsy) or a famous person who experienced it (Lou Gehrig’s Disease, Münchausen syndrome, even Cesarean sections).

And there’s a large group of “toponymous diseases,” like Ebola – named for the place where they originated or were first noticed. Lyme disease first occurred in Lyme, Connecticut, and German measles was first recorded by doctors in that country. The Asian flu, the Hong Kong flu and the Spanish flu all originated in the locales for which they are named, as did Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS). Marburg virus, African sleeping sickness and Argentine hemorrhagic fever are other notable toponymous diseases.

Lassa fever, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, West Nile virus, and Guinea worm disease all began in the areas they’re named for, though they also spread beyond those areas: to name a disease for a particular region, of course, doesn’t magically constrain it to that area. From the small river that provided Ebola with its name in 1976, the afflicted area of West Africa now covers many tens of thousands of square miles and will certainly spread further.

One of the most fascinatingly xenophobic examples of a toponymous disease is syphilis. Its colloquial forms have explicitly served to mark it as something that came from elsewhere. Depending on who was speaking, it might be the English disease, the Italian disease, the Polish disease or the Spanish pox. The Turks called it the European disease. The word “syphilis” itself was coined in a 16th-century Latin epic poem – "Syphilis sive morbus gallicus" (“Syphilis or the French Disease”) – by Italian writer Girolamo Fracastoro.

Certainly the front lines of the war on Ebola involve nurses, doctors, researchers, public health workers, the pharmaceutical industry, the UN, the WHO, the CDC and an array of other institutional partners and funders. At the same time, though, on a wider and more indirect cultural level, our society’s response to this global crisis is inflected significantly by how we talk about it, how we think about it, what vocabulary and terms and discourse we bring to bear on the subject.

My own contribution to this discussion is infinitesimal compared to so much other necessary engagement with the current West African disaster, and yet it may help in some small degree to illuminate how we might work to imagine and understand the situation there as clearly as possible.

In my modern novel seminar we just finished reading Joseph Conrad’s "Heart of Darkness," a story about people who lived in the same country (then known as the Belgian Congo) that was the site of the original 1976 Ebola outbreak, and who experienced an intentional assault on their society and their humanity at the hands of Western imperialists. As the fictional character Marlow sailed up the Congo River to meet Kurtz, the renowned trafficker of ivory and murderer of any Africans who stood in his way, I wonder if he might have passed by a fork for that small tributary, the Ebola River.

Kurtz’s famous dying words – “The horror! The horror!” – carry an oddly haunting resonance today, however accidentally, as we think about the current plight of Ebola victims.

Shares