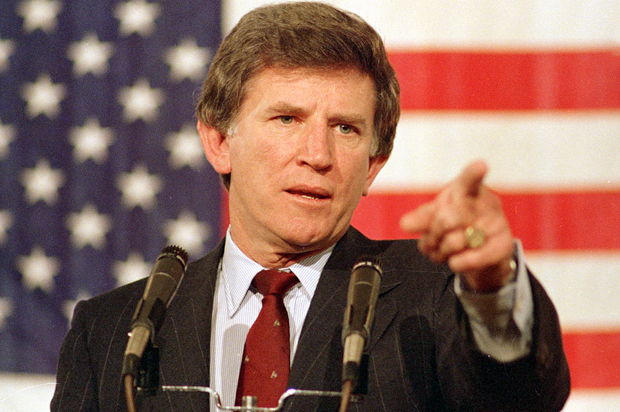

“Have you ever committed adultery?”: A simple, if aggressive, question, but that single query, writes Matt Bai in his powerful and persuasive new book, “All the Truth Is Out: The Fall of Gary Hart and the Rise of Tabloid Politics,” was the hinge on which the fate of American political journalism — and by extension, American politics itself — turned. The question, asked by Washington Post reporter Paul Taylor at a press conference in New Hampshire on May 6, 1987, marked the collapse of Hart’s presidential campaign as well as the end of a decades-long tradition of journalists deeming the intimate peccadillos of politicians to be out of bounds.

The Gary Hart scandal now seems a faded relic of the ’80s, along with big hair and shoulder pads, but Hart himself has never been able to escape its shadow. According to Bai, he continues to be regarded in Washington as “a brilliant and serious man, perhaps the most visionary political mind of his generation, an old-school statesman of the kind Washington had lost the capacity to produce.” Prescience, in particular, was Hart’s forte: He anticipated the need to modernize America’s industrial economy, to plan for energy independence and to correct the Reagan-era financial deregulation that left the economy susceptible to the “recklessness of the markets.” Perhaps most famously at all, Hart predicted the nation’s vulnerability to stateless international terrorism long before 9/11. Yet because the president best positioned to deploy Hart’s gifts — Bill Clinton — was notorious for exactly the same personal weakness that scuttled Hart’s career, his administration shied away from association with the disgraced former senator.

As Bai sees it, the sex scandal that deprived us of the potential boon of Hart’s public service was the result of a confluence of forces. Hart was a Kennedyesque figure embarking on a second and seemingly charmed presidential campaign, when reporters at the Miami Herald received a call from a woman who claimed her friend was having an affair with the candidate. She asked what the paper would pay for photos that proved it. The Herald paid nothing, but gathered enough intel from the treacherous friend to follow the young woman, a model-actress named Donna Rice, from Florida to Hart’s townhouse in Washington, D.C. After observing her enter with Hart, the reporters spent the evening surveilling the place until Hart emerged the next morning, whereupon they confronted him with questions about his overnight guest.

Hart’s womanizing (Bai finds the term old-fashioned but it does seem to fit) was well-known about town. He had for a time been separated from his wife, Lee, and during that period he’d crashed on the couch of Post reporter Bob Woodward — that is, when he wasn’t staying with one female friend or another. The Harts were high-school sweethearts who had escaped a claustrophobically religious small town together, but their marriage was bumpy; she didn’t like politics and spent most of her time at their home in Colorado. (The couple remains married to this day.) Hart amused himself in the way countless politicians had before him, but he made the mistake of doing it at the wrong historical moment.

One of the most impressive aspects of “All the Truth Is Out” is how exquisitely Bai balances a tick-tock account of the burgeoning scandal and the people who made it with a rich depiction of the cultural and political context. Hart was a pawn of the changes that enabled his downfall, not their cause. He didn’t, Bai insists, so much trigger “a dangerous vortex on the edge of our politics” as become “the first to wander into its path.”

Some of the transformations that presaged the Hart scandal were social, like a new generation of college-educated journalists who were inspired by Woodward and Bernstein’s heroic role in investigating the Watergate break-in. Besides chasing exposés, this Boomer cohort, Bai observes, was more focused than earlier newsmen on pondering psychology and “character” — as opposed to policy and arguments. Cable news networks had emerged, with their insatiable hunger for both telegenic stories and combative, pundit-driven talk shows. A series of technological innovations, from videotape cameras to mobile satellites, made it much easier to report live from remote locations. After the scandal broke, an aide went to visit Lee Hart in the couple’s rural cabin in Colorado and was shocked to see satellite dishes lined up outside the gate. “Holy shit,” he thought, “they move now.”

With all these advances, “what might have been a minor story in years past,” during the sober heyday of print, Bai writes, “could now explode into a national event, within hours, provided it had the element of human drama necessary to keep viewers planted in their seats.” Television fostered the elision of news into entertainment. This meant that important but complex and unglamorous stories — like the Iran-Contra hearings, which unfolded at the same time as the Hart scandal — took a back seat to simple and sensational fodder: philandering politicians and crooked, blubbering televangelists like Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker.

Bai is himself interested in “character,” specifically in nuanced journalism rooted in long, frank conversations and interactions with his subjects. His role model — the late, great Richard Ben Cramer, author of “What It Takes,” a classic, 1,000-page chronicle of the 1988 election — worked in just this way. Bai, who covered the 2004 and 2008 presidential elections for the New York Times Magazine, envies the access Cramer enjoyed back then. Today’s candidates, he writes, are “like smiling holograms programmed to speak and smile but not to interact, so that it sometimes seemed you could run your hand right through them.” He recalls an interview with John Kerry in which Kerry became wary and and started hedging after Bai noticed the candidate rejecting a bottle of Evian water. Kerry was actually (and, one must admit, understandably) concerned that his preference in bottled water, if reported, might somehow be used against him.

“All the Truth Is Out” is a genuine portrait of Hart, who now, of course, has little to lose and may speak (as well as select his brand of bottled water) freely. Nevertheless Hart retains a certain reserve. Although he was “the first serious presidential contender of the 1960s generation,” the candidate’s own role models were the stoic and very private men of the post-Depression generation who surrounded him in his youth. He was always happy to sit down and talk ideas with journalists he respected, but he never believed they were entitled to the details of his personal life. Before the story of his affair with Rice broke, the consensus among the younger political journalists covering the race was that Hart was “weird” and “a loner.”

Whether Hart’s sex life should be a story at all was debated. A Times reporter recalled how, 24 years earlier, he’d seen “a prominent actress” entering and leaving the Carlyle Hotel while President Kennedy was staying in New York City. “No story there,” his editor told him. The discretion observed by journalists about such matters was still in place, but had become very wobbly by the time Hart’s campaign for the Democratic Party’s nomination was gathering steam. The subject of his infidelities inched its way through journalism’s door. It began with an allusion made by a Newsweek reporter, who floated the idea that Hart’s personal life might be a problem for the campaign. This made E.J. Dionne, assigned to profile the reticent Hart for the New York Times Magazine, feel that he had to ask about it or risk being accused of writing “a naive profile that acted as if I did not know this was potentially an issue.” It was in that profile that Hart encouraged the press to “Follow me around … If anybody wants to put a tail on me, go ahead. They’d be very bored.”

Contrary to popular belief, the Miami Herald’s stakeout was already in place when the paper’s lead reporter read the “follow me around” quote in an advance copy of Dionne’s profile. Hart’s challenge only served to confirm a choice that had already been made. Both stories — the New York Times Magazine’s in-depth portrait of the candidate and the Herald’s somewhat rushed report on Rice’s visit to the townhouse — hit the newsstands on the same day.

“All the Truth Is Out” offers a terrific portrait of how news gets made, the web of double-checking and second-guessing that editors engage in when competing with other news organizations. It’s riveting, a slow-motion car crash. No one involved in the Hart scandal felt great about reporting it, and all of them describe being caught up in an inexorable process, one in which beating the competition and owning the story (however distasteful it might be) forced their hands over and over again. Taylor professed to be the least conflicted. He had “managed to protect the nation from another rogue and liar” by exposing Hart’s hypocrisy, he believed. Yet even his own reporting on Hart’s equivocal response to “the Question” adopted a striking passive voice (“new ground was broken in the nature of questions put to a presidential candidate”). Later, Taylor left journalism entirely.

Bai believes that the Hart scandal ushered in the current era of gotcha journalism, with politicians regarding working journalists as enemies and striving above all to avoid making the smallest misstep. Personal foibles once overlooked by the political press as immaterial to a public figure’s ability to govern are now deemed essential clues to a his or her moral hygiene. As a result, the pool of candidates is reduced to those with an unlimited, rubbery capacity to absorb abuse, like Bill Clinton; an appeal “almost entirely grounded in the culture of entertainment,” like Barack Obama, or the Ken-doll-like automatism of Mitt Romney, “who outwardly looked the part of a president but who exuded a vast inner reservoir of nothingness.” Someone like Hart, who insisted that his abilities and ideas — not his “story” — qualified him to lead, and that his personal life was nobody’s business but his own and his family’s, simply will not fit, however talented.

In comparison Bai waxes nostalgic about the era when pols and journos would grab a couple of beers together and shoot the breeze, when leaders and the people who reported on them actually got the chance to know each other. Although he acknowledges that some critics view the political journalism of that time as overly “cozy ” or even corrupt, he can certainly point to the current state of the profession as dull, ineffective, petty and dishonest. But those older practices also emerged from a group of people — candidates and reporters — who were an awful lot alike. Would LBJ have quipped, “One more thing, boys. You may see me coming in and out of a few women’s bedrooms while I am in the White House, but just remember that is none of your business,” if the press corps he addressed were not made up of boys? And perhaps some of the behavior the press used to wink at — heavy drinking for example — should not have been so readily granted a pass.

That doesn’t, however, undermine Bai’s shrewd observations on the miserable state of contemporary political journalism (and politicians). Or, for that matter, his bracing ability to assess a public figure’s media persona while at the same time recognizing that’s all it is — a persona. The media, as Hart experienced, pick and choose raw material from an individual life and fashion an image that often bears only a slim resemblance to the human being behind it. What matters is not who someone really is or what he has done. What matters is the symbolic need he meets. While Bill Clinton was forgiven for much crasser sexual misbehavior than any Hart engaged in, Hart could not live down Donna Rice or that infamous photo taken of the two of them aboard a chartered yacht called Monkey Business. Bai blames the indelibility of that image on our own collective bad conscience. We all, he argues would prefer to stow Hart away because he “served to remind us of the decisions we had collectively made, the moment when the nation and its media took a hard turn toward abject triviality.”