In the fall of 1990, Brown University gained notoriety when graffiti naming alleged rapists was found on the stall walls of a central campus bathroom. Though the series of scribbles in the stall was as much a conversation as a collection of names, it came to be known around campus as the “Rape List.” It began with a single sentence inscribed inside a stall. There, in a forum that guaranteed a female-only audience and anonymity, a woman had written, “_______ _______ is a rapist.” The man she named was a Brown student. Over time other women added other names along with complaints about the university’s failure to adequately discipline Brown men who had sexually assaulted female students.

The dialogue on the stall walls continued quietly for months as the list grew to perhaps twenty names. When the school newspaper alerted the university to the underground list, the campus erupted into controversy over concern that innocent men might be targeted. By mid-November, the story had appeared in the New York Times.

What did not make the front-page news was that for years women had tried to bring charges against many of these same men through official channels. I was one of those women. I reported a case of sexual misconduct to the police department (like at many urban colleges, campus police and the city police have overlapping jurisdiction). It interviewed the men involved, who admitted to their participation in the incident, but said they were just joking around. The police investigation stopped at that point, and the complaint was channeled to the dean of students. He met with the accused men and later told me that there was no need for a hearing because they had confessed to their involvement in the incident. He then turned the case over to the football coach to mete out punishment: extra laps at practice.

I expressed outrage at the lax disciplinary measures and demanded something more substantial and permanent. This ultimately resulted in a Letter of Warning to the perpetrators—for alcohol policy violation, but not for sexual misconduct—and a polite suggestion that they write me a letter of apology.

As was typical in cases like mine, alcohol became a mitigating rather than an aggravating factor and was used to sidestep the issue of the resulting sexual misconduct. The dean felt he lacked the authority to punish any offense sexual in nature because, at that point, no explicit provision prohibiting sexual misconduct existed in the Code of Student Conduct (though there were general provisions against harassment and assault.)

The next semester, I attended a forum where I met three other women who knew of or had been through experiences similar to mine in dealing with the disciplinary system for sexual misconduct complaints. We attempted to work with administrators during that spring and summer to make the system work better for women, but our input was continuously ignored or dismissed. Therefore, we were very surprised when the exposure of the bathroom graffiti garnered such immediate administrative attention.

The University Reaction

The university issued a directive to have all graffiti removed, which in practice translated to all graffiti written by women, which only caused the “Rape List” to reappear in bathrooms all over campus. Janitors still continued to scrub it off every day. Women began writing in indelible ink. The white bathroom doors were then repainted black. Women responded by writing in white or metallic “paint” pens. Meanwhile, misogynistic graffiti that blanketed public areas of campus—library carrels, sidewalks, cafeteria tables—remained untouched.

Robert Reichley, Brown’s then-executive vice president of university relations, denounced the list as “anti-male” and the women who created it as “Magic Marker terrorists.” By equating being “anti-rape” with being “anti-male,” Reichley appealed to an aged stereotype that pits men against women in a debate about injuries that men have perpetrated against them. He also implicitly equated being “anti-rape” with being “anti-sex,” making women the embodiment of a New Puritanism hostile to sexuality itself.

A professor of Slavic languages, Robert Mathiesen, warned the graffiti writers to beware of witch-hunting, comparing them to “notorious 15th-century inquisitors.” Historically, witch-hunting was sanctioned by the male judicial system, and most of the people who were “hunted” as witches were “deviants” who in some way were not seen to fit the role prescribed for women. Often they were expressive (either verbally or sexually) of their discontent with their role in society. The practice of witch-hunting created a mechanism for hegemonic institutions to constrain women seen as stepping out of their place.

The then-dean of the college, Sheila Blumstein, compared the graffiti-writers to Nazis and referred to their actions as “vigilantism.” A student soon followed the dean’s lead and widely circulated a flier on “feminazis,” likening women activists to the Gestapo. Like accusations of misandry, “Magic Marker terrorism,” and witch-hunting, accusations of Nazism continued to be hurled in the debate.

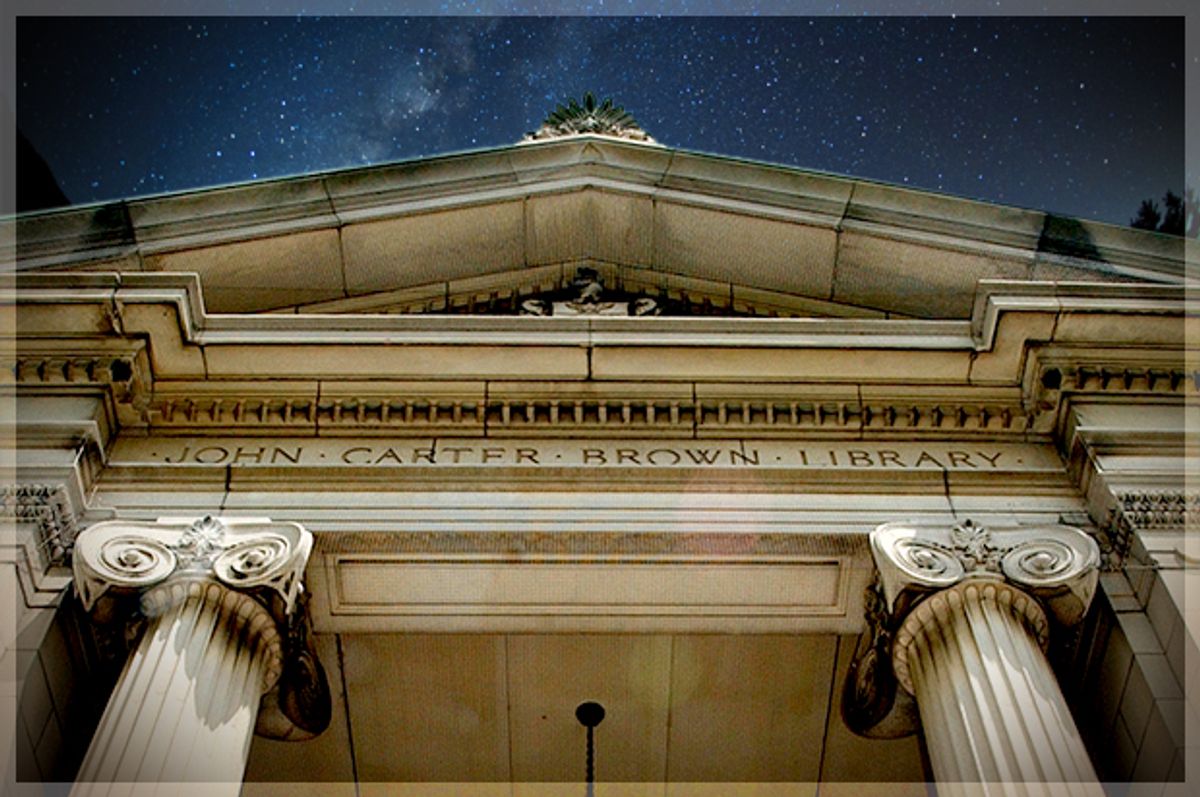

And Vice President Reichley’s press statements continued to illustrate who was a full citizen in the college community and whose injury got recognized. He explained that “[w]hen you pay the princely sum of $20,000 a year to go to this august institution, you ought to have some reassurance that when you are defamed . . . the institution cares about it.” He never addressed whether you ought to have some reassurance that when you are raped, the institution cares about it.

In fact, the university went so far as to set up a grievance procedure for men who had been listed. David Inman, then-dean of students, sent a letter of notification to every man named in the bathroom graffiti. The letter extended an invitation to file a complaint and receive counseling for the injury as well as a guarantee of support from the police. Yet women who wanted to file complaints were never steered toward initiating disciplinary action against an assailant, and no case of sexual assault had ever reached a full disciplinary hearing.

Nevertheless, when the dust finally settled, the movement we led at Brown ultimately resulted in a sexual misconduct provision being added to the disciplinary code, training about sexual assault for all incoming freshman, a reorganization of the Office of Student Life, and the appointment of a dean of women’s concerns. Significantly, Brown finally started hearing such cases and perpetrators began facing consequences.

Déjà vu

Flash forward almost 25 years and campus sexual assault is again front and center news. This time around, women are now getting hearings, but they are often little more than kangaroo courts run by inept and insensitive administrators and faculty. The men are usually cleared, and even when found guilty, receive lenient punishments.

The New York Times did a long-form investigative piece on a student, Anna (the article used only her first name), who was gang raped at Hobart and William Smith Colleges by three football players. At a disorganized and rushed hearing, the adjudicators interrupted her repeatedly and misrepresented evidence. Two of the three panel members did not even see hospital records showing “blunt force trauma” and semen in her vagina and rectum. The football players were ultimately cleared.

Another student, Emma Sulkowicz of Columbia University, charged a classmate with raping her. Six months later, an internal university panel questioned her about various sexual positions and whether she “really” could have been anally raped without lubricant. They ultimately found her assailant not guilty. As an act of protest, she carries a mattress around campus as both a literal and metaphorical albatross.

Last week, a woman named Lena Sclove and I were in a New York Times Op-Doc, Brown’s ‘Rape List,’ Revisited. It focused on how Brown University mishandled Lena’s sexual assault, and my case 23 years earlier, as well as the activism that sprung from both cases. After a friend of Lena’s raped her, Brown’s disciplinary hearing found him in violation of, among other things, “Sexual misconduct that includes . . . penetration, violent physical force or injury.” He was suspended from the University for one year, but Lena still had two years to go before graduating. It is mystifying why Brown would allow her attacker back on campus during her tenure, or at all, given the nature of his offense. Lena ultimately withdrew from Brown.

When I first heard about Lena’s story, I felt angry and disappointed—angry at how Brown failed to protect her and disappointed that all our work decades ago was for naught. Then, as now, things only seem to happen when survivors of sexual harassment and assault are willing to go public and when universities start to get bad PR. But in today’s activist landscape, students have two additional tools with which they have been able to build the most organized, visible and effective anti-rape movement ever: Title IX and social media.

New Tools: Title IX & Social Media

Under Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, which bar gender discrimination, universities are required to have prompt and equitable grievance procedures in place for survivors to take disciplinary action against their perpetrators. The rationale is that sexual harassment and assault hinder students’ equal access to education, which is a fundamental civil right. This does not preclude a student from also going through the criminal justice system, but the courts have a notoriously dismal record when it comes to sexual assault, and it can take years for a case to unfold, by which time both students may have already graduated.

Not only do campus disciplinary hearings offer the possibility of a speedy remedy (federal guidelines say colleges typically take 60 days to investigate cases), but the standard of proof, mandated under federal guidance issued in 2011, is lower than the “beyond a reasonable doubt” burden of proof for criminal cases. Campus cases rely on a “preponderance of the evidence” standard: whether it is more likely than not that a student violated university rules.

If campus disciplinary systems fall short, a survivor can file a Title IX complaint with the U.S. Department of Education to initiate an investigation into their school’s policies and practices. That’s exactly what Erin Cavalier did when Catholic University ignored her complaint after an acquaintance raped her. After her federal complaint that she was “forced to lobby, argue and fight for a grievance hearing,” Catholic soon reversed itself. While the hearing eventually exonerated her attacker, she, like the other women mentioned in this article, has gone public to illustrate how the University mishandled her case and is using Title IX to fight back. Today, the Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights is investigating 78 American colleges—including Hobart and William Smith Colleges, Columbia, Brown, and Catholic—for their handling of sexual assault cases, based on Title IX’s prohibition of gender-based discrimination.

That’s where social media enters. As in the past, educational institutions often respond to bad publicity more than bad injustice. But while my activism in the 90s garnered a New York Times article and an episode of the Phil Donahue Show, such spotlights are amplified by an order of magnitude thanks to social media. Additionally, social media has also allowed students to better organize with each other across campuses, to learn their legal rights and how to exercise them, and to strengthen survivor advocacy.

It saddens me deeply that Lena did not feel comfortable finishing her college career at Brown, a place I truly love. Sexual harassment and assault on campus are a nationwide epidemic, which now has the attention of not only university presidents, but the President of the United States. I never thought that would be possible. Or that it would be necessary.

Shares