If there's a single historical moment that captures what the author Karen Armstrong wants to convey in her new book, "Fields of Blood: Religion and the History of Violence," it's the Christmas-Day coronation of Charlemagne in 800. "Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne 'Holy Roman Emperor' in the Basilica of St. Peter," she writes. "The congregation acclaimed him as 'Augustus' and Leo prostrated himself at Charlemagne's feet." If you want to blame the human race's long, ghastly history of bloodshed on religion, Armstrong argues, be aware that faith is more often the servant than the master of politics.

"Fields of Blood" is panoramic work, even at a judicious 400 pages (excluding notes). It takes in the ancient civilizations of Mesopotamia, India and China before settling down for a good long look at the Abrahamic traditions: Judaism, Christianity and Islam, with the occasional side trip back to India when sectarian clashes heat up there. Throughout, Armstrong deploys the confident, even-handed and congenial voice that made "A History of God" (1993) and "The Battle for God" (2000) bestsellers. And her points are eminently reasonable. Religion, she insists, takes many different forms and "to claim that it has a single, unchanging and inherently violent essence is not accurate. Identical religious beliefs and practices have inspired diametrically opposed courses of action."

As enjoyable and informative as "Fields of Blood" is, it's a great deal of scholarship to expend on supporting an observation that seems pretty obvious. Is there anyone who actually believes that religion has been the cause of all the major wars in history? Apparently yes, as Armstrong reports having heard versions of this statement from "American commentators and psychiatrists, London tax drivers and Oxford academics." Yet the claim is so easily refuted by a quick look at the two World Wars -- not to mention, say, the Russian Revolution, the American Civil War and the Mongol Invasions of the 13th and 14th century -- that you have to wonder if the people making it actually care about its historical accuracy.

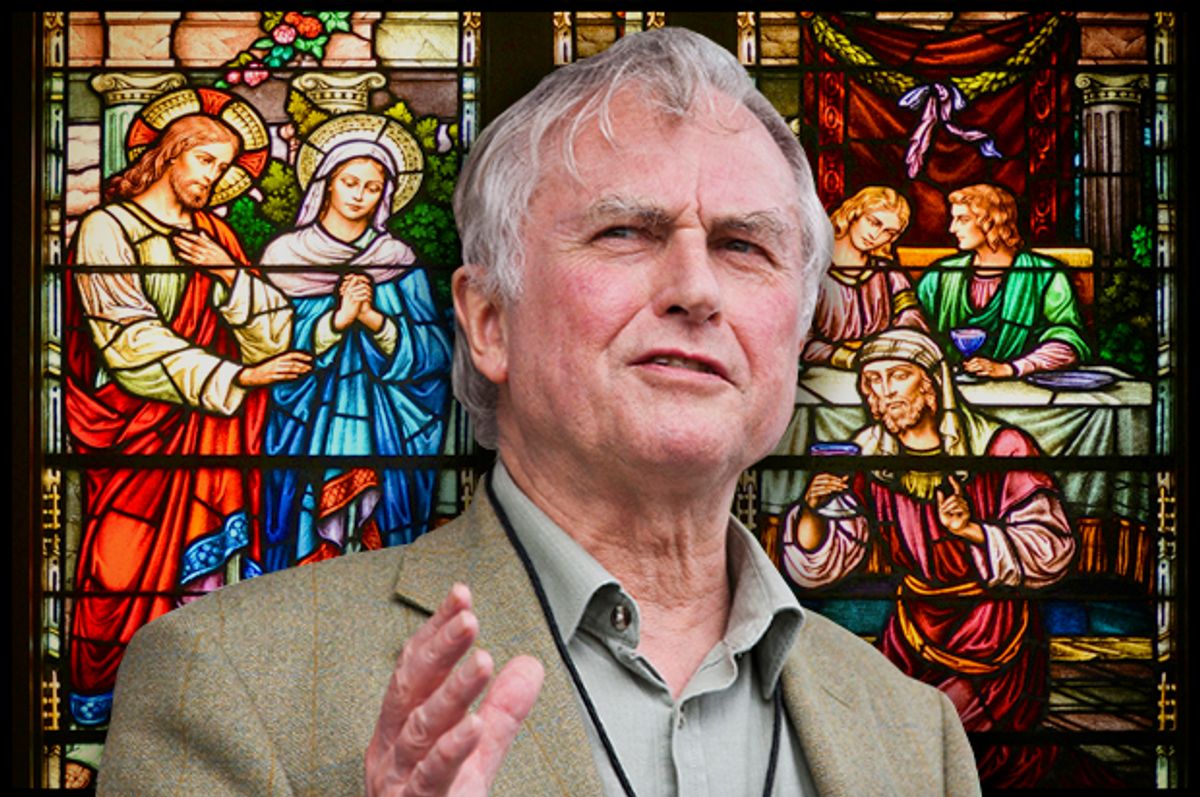

The closest Armstrong comes to naming an advocate of the "all wars are about religion" line is when she quotes biologist, author and stridently public atheist Richard Dawkins in her chapter on terrorism. "Only religious faith is a strong enough force to motivate such utter madness in otherwise sane and decent people," Dawkins wrote in "The God Delusion." But, again, as Armstrong briskly notes, the suicide bombing was invented by the Tamil Tigers, a secularist group, and for many years they held the record for committing such acts. Furthermore (although Armstrong doesn't bring this up herself), it wasn't religion that led Rwanda's Hutus to hack to death nearly 1 million of their fellow citizens, including neighbors of decades, in perhaps the most insane and indecent homicidal eruption of the past half-century.

At this point in time -- with his sweeping, unsubstantiated and historically ill-informed polemics -- Dawkins has dug his own intellectual grave. Still, the question remains: How much of the planet's history of can be laid at the feet of religion? For the vast majority of human existence, Armstrong argues, "religion" could not be separated from politics or economics or any other social institution; the idea of doing so would literally have made no sense to the members of any pre-Enlightenment culture. "Until the modern period," Armstrong writes, "religion permeated all aspects of life, including politics and warfare, not because ambitious churchmen had 'mixed up' two essentially distinct activities, but because people wanted to endow everything they did with significance. Every state ideology was religious ... Until the American and French Revolutions, there were no 'secular' societies."

But there was power and wealth, and the way Armstrong tells it, just about every historical instance of armed conflict was rooted in both, with religion mostly serving as a legitimizing veneer or justification. In the panoramic view offered by "Fields of Blood," faith is an undulating force, like the tide, sometimes rushing toward power and sometimes pulling away in moral horror.

Take the Crusades and the period leading up to them in Europe. Pope Leo II knelt before Charlemagne because only a strong military leader could raise and control enough armed men to defend the Church from invading barbarians. In time, the region later known as France would be harried by these knights, minor nobles who considered plunder the only honorable income source for members of their class. Popular opposition to the depredations of the aristocracy and the corruption of their clerical allies pointed out how un-Christian their behavior was. Reformers established "the Peace of God," a movement that recast the ideal knight as "a soldier of Christ" sworn to defend the poor and weak. So chalk one up for religion as a force for good there.

The first successful call for a crusade to the Holy Land came from Pope Urban II, who recognized it as an excellent way to siphon off the warlike energy of otherwise unoccupied knights and soldiers. But the Crusades also served him a means of reasserting the power of the Church to defend Christendom at a time when he was wrestling with the Holy Roman Emperor for dominance. Many of the crusaders were fired with religious fervor, but that didn't keep them from pillaging and slaughtering at will, and others were basically in it for the loot and the killing. The barbarism with which the First Crusade took Jerusalem appalled the cosmopolitan Muslims who had previously occupied the city. As they saw it, the Europeans had trampled all civilized standards of warfare because they "did not spare the elderly, the women or the sick." When Saladin retook the city in 1187, he shamed the Christians by showing far greater mercy than they had -- because a Christian talked him into it.

Similarly, the Shiites' disillusionment with early struggles for leadership in the Muslim world led them to forswear politics and other worldly concerns. To be holy was to be withdrawn from such things. It took the brutal 20th-century dictatorship of Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi -- and the hypocritical American government that supported him -- to persuade the Ayatollah Khomenini to argue that Iran should be rule by the ulema, or Muslim scholars. The proposal, Armstrong writes, "was shocking to most Shiites," and was also strongly influenced by "Third World intellectuals who defied global structural violence" perpetrated by Western powers, whether as liberation theologists in Latin America or Marxists in Asia. It was a "fundamentalism" infused with modern ideas and demands.

By "structural violence," Armstrong means the force by which any developed, and therefore stratified, society imposes social, economic and political inequality. This is the "dilemma of civilization, which cannot exist without ... structural and military violence," the former to keep the underclasses in line and the latter to defend against outsiders who come after its resources. Religion can often be used to support these two types of violence, but it also offers a retreat, sanctuary or utopian alternative to those who are sickened by them. The genius of the Shiites faith is, "the tragic perception that it is impossible fully to implement the ideals of religion in the inescapably violent realm of politics"

Armstrong sees the desires, actions and beliefs of most civilizations as being ultimately shaped and driven by political and economic needs. It was industrialization and the demands of capitalism that inaugurated the ideal of a secular society, first in the United States and later in Europe. But secularism cannot, in Armstrong's mind, supply the average person with the sort of meaning and transcendence found in religion. It replaced faith with nationalism -- sometimes literally, as during the French Revolution, when Catholic churches were purged and filled with idols representing the new republic. But while Armstrong claims that "all the world's great religious traditions share as one of their most essential tenets the imperative of treating others as one would wish to be treated oneself," nationalism, she says, can't encompass the notion of a larger brotherhood of man.

Although she doesn't come right out and say so, Armstrong is implying that the mass-scale bloodbaths of the 20th century were at least in part facilitated by this weakness in secular nationalism. Far from causing the worst wars, religion in a way prevented them, until secularism came along to lose the really big dogs of war. Even what we like think of as the quintessential form of modern religious fanaticism, militant Islam, is often just nationalism in the sheep's clothing of faith.

Without faith-inspired compassion and the ability to see all human life as sacred, Armstrong feels, it's too easy for secular societies to treat minorities and outsiders as insignificant and disposable. But as Armstrong's own history lesson demonstrates, even when principled believers objected to the brutal behavior of their co-religionists -- for example, during the European conquest of America or the exploitation of the peasants and poor just about everywhere at any time -- they seldom had much effect. Self-interest, often rankly hypocritical, seems to win out every time.

Nationalism isn't the only ideal secularists believe in, either. It's perfectly possible to revere human life and the human spirit without being urged to by supernatural forces; that's called humanism, and it too defies the clannish passions of nationalism. It also has a more considered understanding of religion itself, recognizing it as an element of every human society, one that has the capacity to inspire great generosity and courage, but also the propensity to endorse great evil. That's an awareness that most religions can't entertain about themselves. If Armstrong wants to argue that what we often think of as religious extremism is in fact nationalism in disguise, then couldn't the great pluralistic civilizations of the pre-secular era -- the Mogul and Roman Empires at their best, for example -- be viewed as humanistic at heart?

These are all provocative and intriguing questions, but it's hard to imagine militantly atheistic people of Dawkins' ilk ever being willing to contemplate them. Anyone dumb enough to claim that religion lies at the root of all wars has already demonstrated a willful indifference to and ignorance of history. More history, real history, is unlikely to change their minds because, as more than one observer has noted, they tend to be just as fanatical as the fanatics they rail against. Ironically, it's the open-minded, those who least need "Fields of Blood," who are most likely to read it.

Shares