Critics have never entirely gotten over "Jesus' Son," Denis Johnson's spare yet hallucinatory 1992 short story collection about a series of addicts and drifters (who might or might not be the same young man), meandering through an underworld of dead-end jobs and petty crime. It's a perfect book, and much of Johnson's later work -- particularly "Already Dead," the "California gothic" that followed it six years later -- has suffered by comparison. Wistful references to "Jesus' Son" crop up in reviews of Johnson's work as reliably as Alfred Hitchcock cameos in Hitchcock films. You're always looking for them.

Most of Johnson's fiction since "Already Dead" has leaned toward the maximalist, the intricate and the paranoid; you could call "Tree of Smoke" a "Vietnam gothic." Even though that novel won the National Book Award in 2007, there remained a lingering wistfulness to much of the praise it earned. Johnson has further confounded expectations by writing shorter books about a grieving, but solidly bourgeoise widower ("The Name of the World"); a hard-boiled crime novel set in Bakersfield ("Nobody Move") and a historical novella about a backwoods hermit in Idaho ("Train Dreams"). He seems unlikely to revisit the style and subject matter of "Jesus' Son" any time soon.

Besides, perfection -- always easier to achieve within strictly limited parameters -- is overrated. The truth is, Johnson's later work, while less exquisite and heart-rending than "Jesus' Son," is in many respects more interesting than his earlier high-MFA-style short stories. It's certainly more fun. Some novelists, like Thomas Pynchon, produce complex fictions packed with ideas and themes and incidents that often don't seem to add up to anything human. Others, like David Mitchell, craft elaborate and inventive narrative contraptions to convey what amount to rather trite sentiments. Johnson can execute all of that tricky stuff -- the plotting of "Already Dead" is a marvel -- without getting lost in a book's conceits and devices. His fiction always has a pulse, the kind with real blood in it.

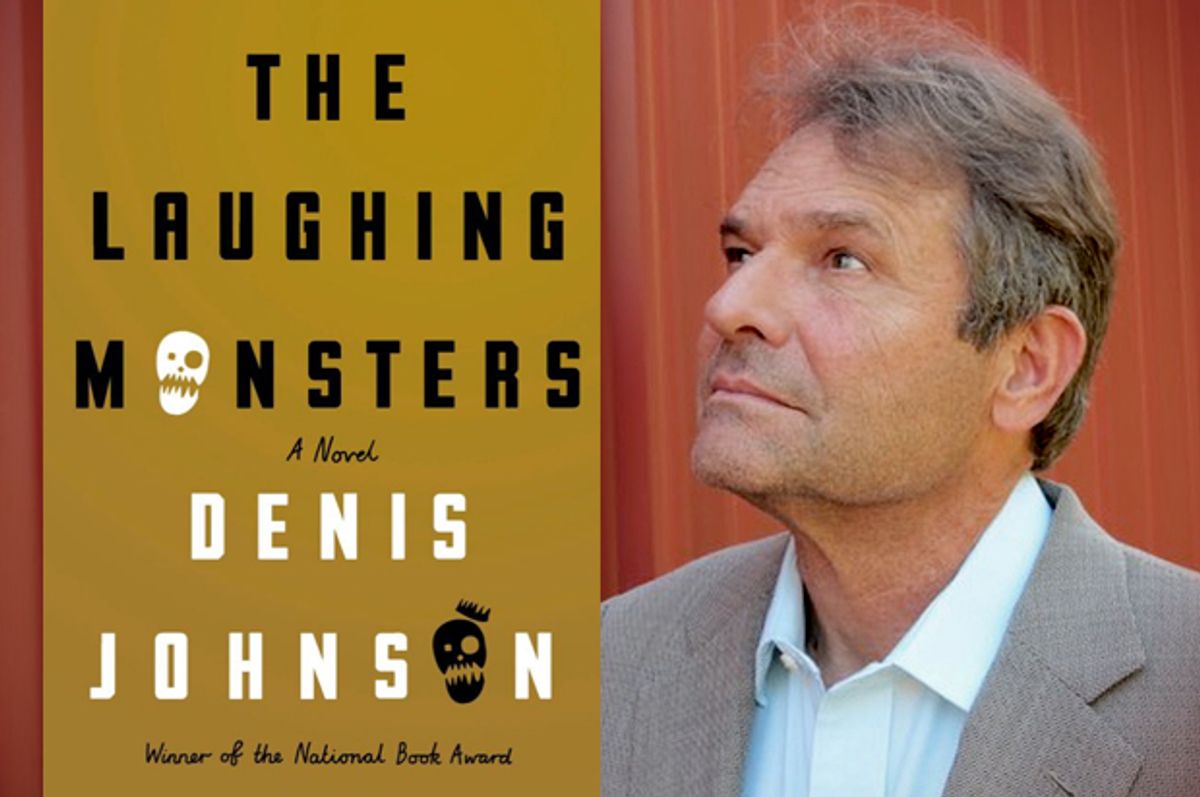

Johnson's latest, "The Laughing Monsters," is a case in point. Ostensibly, it's a gritty thriller set in Sierre Leone, Uganda and Congo. Underneath that, it's about the inability of men of a certain type to lead honorable lives. Africa is infested with such men, decommissioned or semi-commissioned soldiers and spooks sniffing around for dirty jobs and promising scams. The narrator of "The Laughing Monsters" -- half Danish, half American and employed by NATO intelligence -- is sent by his bosses to Sierre Leone to reconnect with an old buddy, Michael Adriko, a Congolese orphan and child of war turned international special-forces soldier. The two of them made a bundle during the civil war on a shady operation involving diamonds.

The narrator's name is Roland Nair, and some allusion to Browning's Childe Roland seems likely, since Nair has been directed by liars to journey across a poisoned landscape and ends up under a tree inhabited by a mad god. In the meantime, though, Nair will revisit his infatuation with Michael -- even if he can't quite admit to himself, at least not at first, that an infatuation is what it is. Michael is magnetic and unpredictable, capable of great violence, cunning and irrepressible hope. "Always laughing, never finished talking," full of plans and mysteries. He wants Roland to join him in his latest scheme. "You'll live like a king," he promises. "A compound by the beach. Fifty men with AKs to guard you. The villagers come to you for everything" --The "everything" includes handing over their virginal daughters -- "Nair, no AIDS from these girls." This, Michael insists, is what they both want, "and you know it's here. There's no place else on earth where we can have it."

On the other hand, Michael also has a beautiful young African-American fiancée named Davidia, a woman he met while training in an Army base in Colorado. And Nair spends most of his free time writing encrypted emails to a lover back in Amsterdam named Tina. (She turns out to be an attorney working for NATO.) Michael's plan entails a bit of flummery that could only work in a post-9/11 world: He claims to have the location of a shipment of enriched uranium thought lost in a jungle plane crash. Eventually, Nair winkles the truth out of him: All Michael's got is a single bogus "sample," but he plans to use it to con a million bucks out of Mossad. His bait is manifestly pretty sketchy, but no Western counterterrorist operation can afford not to take him seriously because the cost of being wrong is too high.

Much later in the novel, Nair will speak with a U.S. official ("I'm the closest thing to Susan Rice") who will tell him, "I can't deny it. Since 9/11, chasing myths and fairy tales has turned into a serious business. An industry. And a lucrative one." But Nair is also running his own con, one that involves selling American secrets to the Chinese. Pulling it off will necessitate betraying Tina back in Amsterdam, even though Nair claims to love her, and to top it all off, he also decides he's in love with Davidia (not much more than a pretty cipher) and tries to steal her from Michael.

So, not nice guys at all, Nair and Michael, and yet they're also not as bad as they seem. It's not power or money Nair is after in Africa: "I love the mess. Anarchy. Madness. Things falling apart." In other words, adventure. "If he thinks I'd like an army and a harem," Nair explains, "Michael mistakes me too. I don't want to live like a king -- I just want to live. I can't make it happen by myself. I've got all the ingredients, but I need a wizard to stir the cauldron. I need Michael." Much, much later in the novel, we'll learn that the payday Nair's chasing doesn't amount to much more than a year's salary, which to my mind is a master touch, Johnson's way of signaling the novel's real stakes.

The prose is, of course, radiant: "As he expressed these ideas he followed them with his eyes, watching them gallop away to the place where they made sense." But "The Laughing Monsters" (titled after a disgusted missionary's nickname for the mountains of Michael's homeland) is anything but spare. As these interlocking blades of plot and counterplot click through a complex series of revolutions -- not least of which is Michael's stated plan to marry Davidia in his tribal homeland -- eventually things do get scraped down to the bone, that is, the bond between the two old friends. "What is desertion?" Michael asks, when it comes out that he's run off from a U.S. Special Forces unit fighting the Lord's Resistance Army in Congo to reunite with Nair. "Desertion is a coin. You turn it over, and it's loyalty."

This addictive expat fug of corruption and doubt and misplaced-yet-oddly-functional love is Graham Greene territory, needless to say. Johnson, who has reported extensively on conflicts in West Africa and Somalia, is, like Greene, a questioning Catholic writer, wandering through a fallen world of unfathomable chaos and unexpected grace that forces him to scrutinize the worst sides of himself. Is it possible to be loyal without being true, good without being moral? For that matter, is it possible to write a thriller that has something real to say about human beings?

Not purely, not even cleanly and certainly not perfectly. There is too much of the world in Johnson's fiction now for him to deliver up the visionary losers who commanded his early stories. He has become, in his own way, baroque, because that's what the world is. If you really want to live in it, and to do justice to the people who inhabit it, you have no other choice.

Shares