Although vaguely positioned as an Oscar-season contender thanks to its stars, its English period setting and its historical and cultural resonance, “The Imitation Game” is forever doomed to be the other 2014 film about a famous Cambridge professor. I’m not sure it’s ultimately a worse movie than the Stephen Hawking biopic “The Theory of Everything,” but it’s much closer to solid, capable British TV drama, and never makes much of a case for itself as a big-screen experience. As middlebrow, medium-impact melodrama goes, you could do worse.

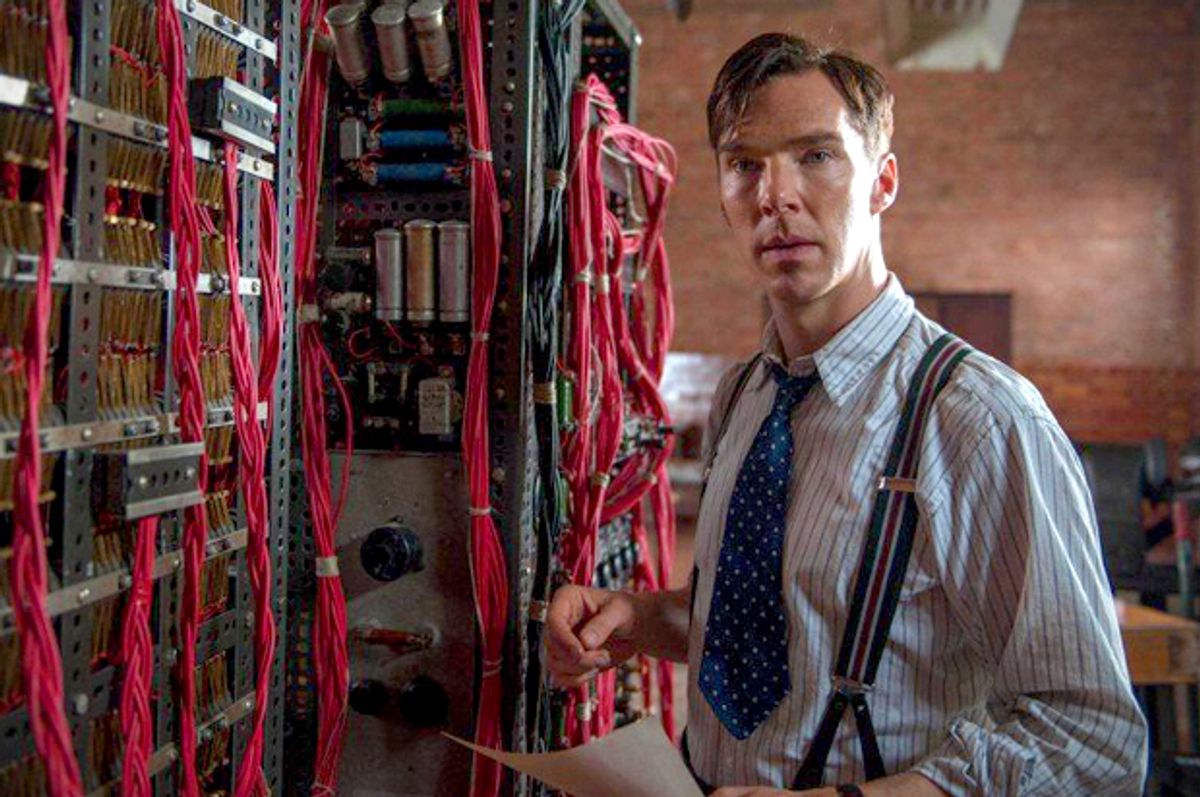

Benedict Cumberbatch, universally proclaimed as the sexiest Englishman ever for his TV role as a proto-queer Sherlock Holmes, may well receive awards nominations for his portrayal of mathematician and cryptographer Alan Turing, who invented one of the world’s first computers, played a key role in winning World War II and then was viciously persecuted for his homosexuality. Sooner or later Cumberbatch is bound to play someone who’s not the smartest duck in the room and who would not, in the diagnostic terminology of the 21st century, be found somewhere on the autism spectrum. But Turing is most certainly not that role, and “The Imitation Game” is more like a dutiful and salutary history lesson than a work of revelation. I enjoyed watching Cumberbatch play Turing as an antisocial accumulation of tics and twitches, but never really forgot that I was watching an actor display his craft. This isn’t quite Cumberbatch’s movie-star breakthrough; if it comes closer than his misbegotten Julian Assange movie, “The Fifth Estate,” that really isn’t saying much.

Turing is a genuinely fascinating and tragic figure in the history of 20th-century science and culture, and if director Morten Tyldum’s film brings renewed attention to his life and work, that’s all to the good. As with the Hawking movie, it’s next to impossible to summarize Turing’s intellectual breakthrough in a screenplay (this one by Graham Moore, based on a Turing biography by Andrew Hodges), but we do get some highlights: Fascinated by codes, ciphers and puzzles since his schoolboy days, Turing had the insight that a programmable calculating machine could do much more than solve arithmetic problems. He may have been the first person to use the phrase “digital computer,” by which he meant a machine that could be programmed to follow a form of basic logic, to draw conclusions from its calculations about what calculations to do next, and to crack any code, through sheer relentless power, faster than any human ever could. He was the first hacker – and he hacked Hitler.

If the most obvious legacy of Turing’s research and experiments is the world around us – as Cumberbatch plays him, Turing would not have been surprised to learn that computing power would increase exponentially, and would leave no area of human economy unchanged – his story is not just about technology. Turing and his team of tweedy geeks, ensconced in a supposed radio factory in the English village of Bletchley Park, remained a state secret until nearly the turn of the century, but they quite plausibly shortened the war by two years and saved millions of lives. Not only did they build a computer that broke the secrets of Enigma, the German code-making machine that was itself a major technological breakthrough, they kept that fact a secret from the Nazis until nearly the end of the war. (It’s far more valuable to read your enemy’s coded transmissions if they don’t know you’re doing it, after all.)

So there’s plenty of drama in “The Imitation Game” even before you get to the uneasy and tormented personality of Turing himself, or the fact that his immediate superiors in military intelligence never understood his work and believed he was chasing phantoms with his magical gizmo. “One hundred thousand pounds?” disbelievingly exclaims Dennison, the bearded military grandee played by Charles Dance, when told the initial price of Christopher, Turing’s code-breaking computer. Turing was at various times suspected of being a Soviet spy, a suspicion that was fed by the homophobia and anti-intellectualism but was nonetheless not entirely illogical. (There were a handful of Soviet moles who worked inside British intelligence during and after the war, and while they weren’t all gay Oxbridge scholars, that was certainly the stereotype.) But Turing wasn’t a Red, although he was unquestionably an undercover operator trying to be something he wasn’t. Turing really did write a technical paper called “The Imitation Game,” but the title of the film also refers to his unsuccessful attempts to conform to “normalcy” in the intensely hierarchical, homophobic boys’-club society of mid-century Britain.

Turing was a semi-closeted gay man whose orientation was understood by his close colleagues, but who had to keep up appearances in an era when hundreds of men in Britain were prosecuted and imprisoned for homosexual acts every year. He faked an engagement with a brilliant female colleague, played engagingly here by Keira Knightley, who seems to have loved him after her fashion and was even potentially willing to accept the unusual terms of their intended marriage. Turing also would very likely have qualified for an autism diagnosis, along with a not-inconsiderable number of other scientists, mathematicians and engineers who understand systems and numbers far better than people. During the most effective scenes of “The Imitation Game,” you can see that Turing, so far ahead of other people’s comprehension when it comes to the possibilities of electronic intelligence, simply cannot keep up with them in other contexts. He simply does not understand that the sentence, “Alan, we’re going to lunch” is meant as an invitation. A dirty joke is even worse: He doesn’t grasp the nature of the joke itself, and does not share the lustful view of women it assumes.

Tyldum handles a cast of stock characters capably; the best of them (beyond Cumberbatch as Turing) is certainly Mark Strong as an unscrupulous MI6 agent who recognizes Turing as a kindred spirit of sorts and is able to protect him, at least while he’s useful to the war effort. But “The Imitation Game” is entirely timorous when it comes to Turing’s private life – if he had actual lovers beyond furtive pub encounters, we don’t know about them – and tries to skirt or sugarcoat the dreadful conditions of his final years. This could have been a story of immense heroism, tragic sacrifice and agonizing historical irony, and it hints in that direction, in its stiff-upper-lip fashion, before retreating into a vain search for a happy ending and an effort to turn itself into “The King’s Speech.”

Shares