BEIJING — At the end of a lonely alley, the building had three rooms, no number and just one entrance. Only after midnight would the lights come on, and they’d stay on until dawn.

BEIJING — At the end of a lonely alley, the building had three rooms, no number and just one entrance. Only after midnight would the lights come on, and they’d stay on until dawn.

The work inside was smelly and dangerous. Three powerful fans whirred through the night. The floor was stacked with charcoal briquettes to absorb the odor.

But the men inside were settling down for a late-night snack — they hadn’t even put on their gas masks yet — when police came through the iron door.

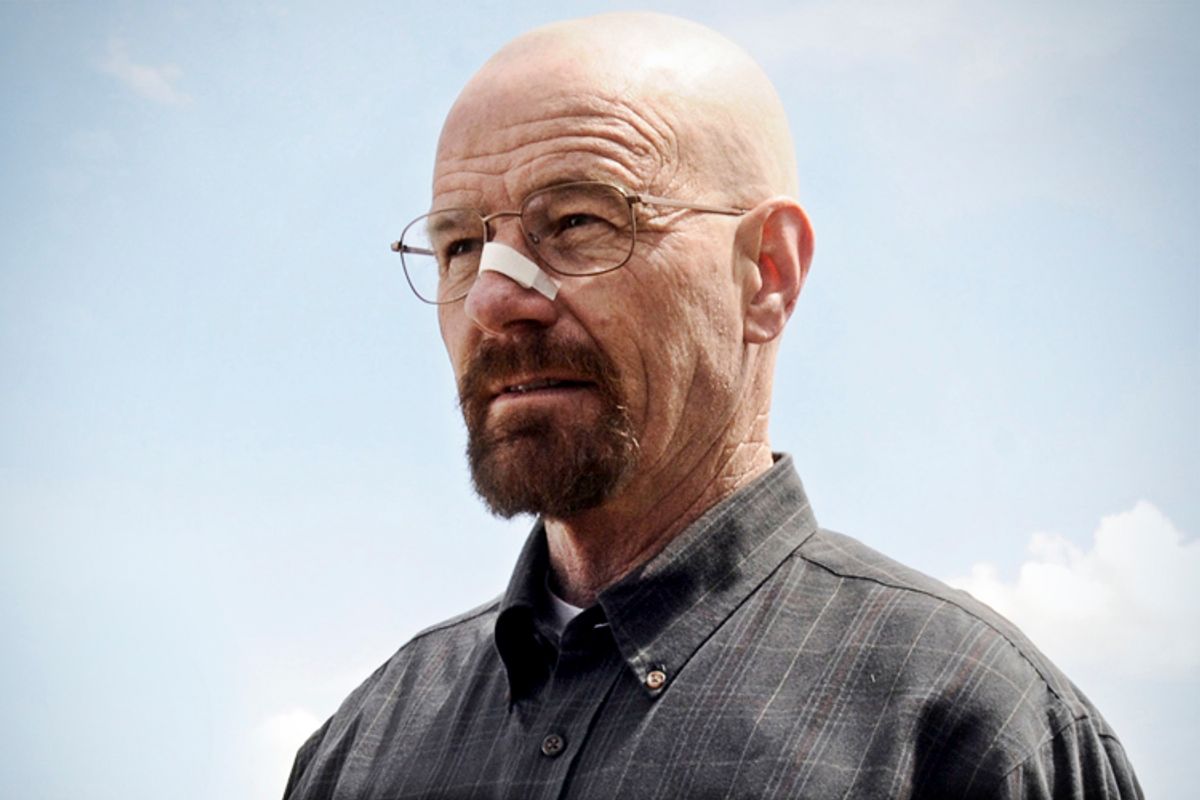

The bust that ensued would give "Breaking Bad" a run for its mythic blue meth.

Simultaneous arrests across the provincial capital of Guangzhou netted members of one of the most notorious gangs in South China, police say. The suspects quickly led authorities to the scheme’s mastermind: a former plastics worker turned meth mastermind, nicknamed “Professor Xu.”

Xu’s story bears striking similarities to that of Heisenberg, the alter ego used in the acclaimed AMC crime drama by protagonist Walter White, a terminally ill high school teacher who begins cooking crystal meth to provide for his family.

But Xu is no professor. He’s the alter ego of “Liao,” a laid-off 58-year-old struggling to provide for his family. Liao’s access, through his former job, to the raw materials needed for meth production made him invaluable. He bought the chemicals around China, and sold them for a profit.

Although he soon landed on the police radar — Liao was arrested once, but released due to lack of evidence — his lifestyle took on the trappings of criminal success. He no longer dealt with clients in person but via telephone and internet. By 2011, Liao had vertically integrated his business, transitioning from middleman supplier into meth-cooking mentor, after teaching himself the process, according to a report in the Southern Metropolitan Daily. The ex-factory worker began traveling, visiting cities in provinces such as Guangdong, Fujian, Hubei and Henan alongside his “girlfriend,” a 30-year-old transgender male from Hunan called Ma.

During his journeys cross-country, he offered provincial meth startups cooking classes at 400,000 yuan (about $65,000) a week and he networked with gangs. Ma, on whom he lavished gifts including a $32,500 car, was not just a consort but part of the scheme, police allege: His small shop in Guangzhou — selling “Hainan specialties” — and a “wholesale clothing business” was merely a cover. Buyers would use instant-messaging services like QQ, and online payment systems such as PayPal, to trade.

China is now a central part of the meth route. Most of the US supply — 80 percent — comes not from domestic trailer parks but Mexican cartels. Their ingredients are shipped from China, the world’s top bulk exporter of the precursor ephedrine, and where the ephedra sinica shrub is both native and used widely in traditional medicine.

China has ready access to opiate drugs like heroin, which come from bordering Myanmar, Laos, Vietnam and Thailand. With opium the main target of overseas drug enforcement agencies, and synthetics more reliable than crops, meth has boomed in both Southeast Asia and North Korea, replacing heroin as perhaps China’s most popular drug.

There’s nothing like "Breaking Bad" on TV here; shows are forbidden from portraying nuanced views of criminal culture, and so meth has little presence in the popular imagination. Crystal meth, also called "bing" or ice — consuming meth is “ice skating” — is widespread because it is cheap and versatile. Truck drivers use it for red-eye runs, shift workers to stay awake and focused. Its popularity on the club scene is still in its infancy, but meth has plenty of young recreational users.

Police zeroed in on Liao through his partnership with the head of a gang from Jieyang known only as “Old A.” Liao held back on trade secrets during his lessons, and Old A, on the run from Jieyang, needed the Professor as a “technology consultant” for his new lab, a 430-square-foot factory in Wufeng, Haizhu, which had a business license to produce fertilizer. The pair installed five young men in a nearby apartment to work the lab at night.

Here, the gang took half-processed 25-kilo barrels of meth for purification and crystallization under the tutelage of Liao, who’d pop by from time to time under his Professor Xu moniker. They could produce 150 kilos in four days, hiding the product in heating appliances couriered to the gang’s old contacts.

From blue-collar worker to meth millionaire, the tale of how a humble family man became an ersatz “professor” and drug lord may seem as strange as fiction. For the police who masterminded his downfall, it is a propaganda coup. But for those left unemployed in their late-middle ages in rural China, Liao might seem more of a folk hero. “I’ve always known this was a good source of income,” joked one commenter. “But sadly my husband only scored four points on his chemistry exam.”

There’s a mythical, outlaw quality to Professor Xu that resonates in a country where rule of law is a tool of the powerful and, unlike the fictional bandits of "Water Margin," outlaws can rarely be celebrated.

Shares