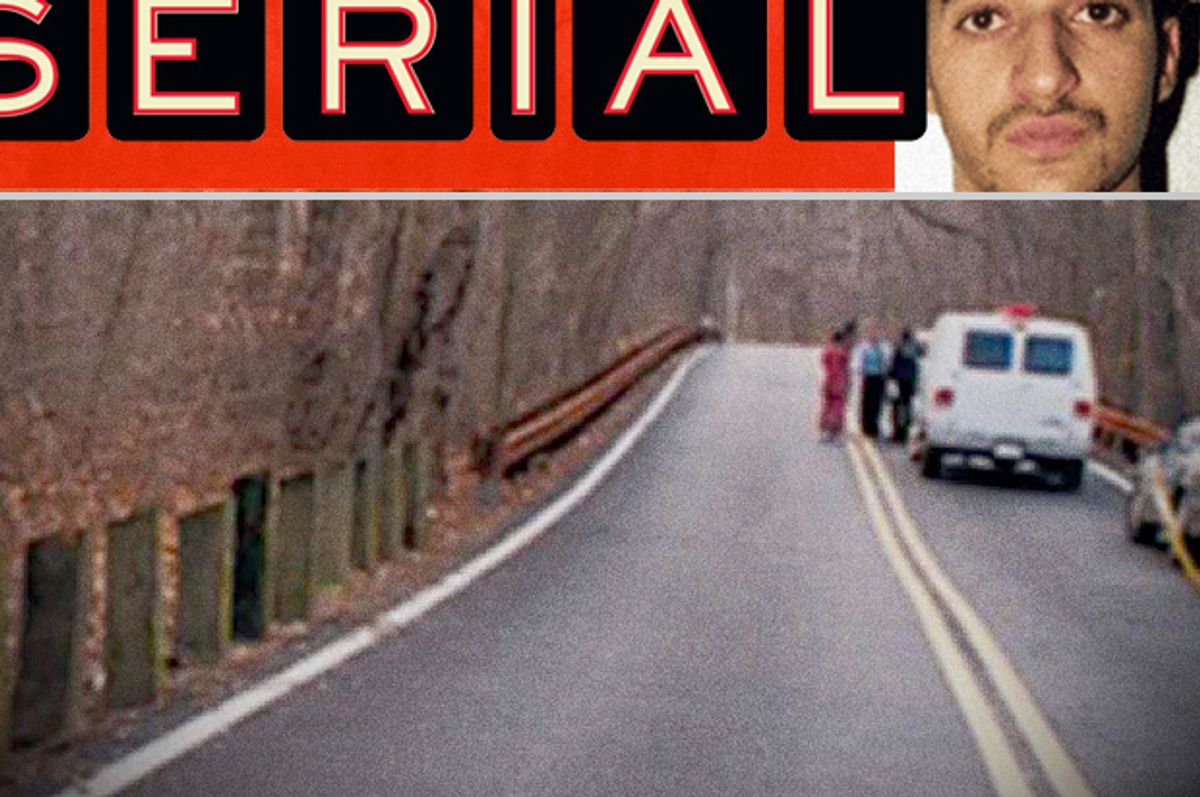

"Certainty seemed so attainable. We just needed to get the right documents, spend enough time, talk to the right people, find his alibi..." So says "Serial" host Sarah Koenig in the closer of the finale episode of the record-breaking true-crime podcast. By episode four, there were plenty of listeners suspecting and groaning over the likelihood of such a conclusion -- "Don't let this be a contemplation on the nature of truth," cried Slate writer Mike Pesca in a podcast about the podcast -- which was very, very likely indeed. You might even say uncertainty has been the only certainty when it comes to the ending of "Serial."

Several intriguing puzzle pieces were introduced. A co-worker of Jay's says that before the cops picked him up, Jay said he knew who killed Hae and that he had been threatened by someone "Middle-eastern" who wanted him to keep silent about it. (To be clear Adnan was an American of Pakistani descent; Pakistan is in South Central Asia, not the Mideast.) The friend believed Jay to be "frightened out of his mind, and not of the police." Dana and Julie scrutinized the cell phone records and extracted an old AT&T customer service agreement from a Gormenghastian court archive in New York to establish that the notorious "Nisha call" could have been an accident. Julie also thinks that both Adnan and Jay were probably lying about what they were doing in the hours before and after Hae Min Lee was murdered on Jan. 13, 1999. And here we are again, lost in the tall grass.

"Serial" has always oscillated frantically between two models of divining the truth: one based solely on material facts and the other on intuition about human nature and individual character. In different ways and at different times, we overestimate both. There's a moment in the "Serial" finale when Adnan's generally affable tone hitches a bit. The Innocence Project has filed a motion to test DNA evidence found on Hae's body, at his request. Maybe it won't make a difference, but, he says, if there's anything more to be learned about his case, he wants to know it. The state has been sitting on this evidence for 16 years, he says, and that's where Adnan's voice skips, on those 16 years. To me, it sounded like someone who failed, for just a moment, to conceal the misery of the injustice he'd suffered. To me, that sounded like an innocent man.

Meanwhile, Dana, the "Mr. Spock" of the "Serial" team, asks if it isn't outlandishly improbable that an innocent Adnan would suffer such perfect storm of bad luck, all of it conspiring to either implicate him or to fail to exonerate him. Dana: meet the laws of probability, which pretty much dictate that bizarre coincidences will occur. Dana's take might sound logical, but probability is in fact wildly counterintuitive; the way the universe actually works often goes against what we consider common sense. Sometimes, we're the most irrational when we think we're being the most rational.

"Several times I've landed on a decision," Koenig says. "I've made up my mind and stayed there, with relief. And then inevitably I've learned something I didn't know before and I'm upended." Perhaps, like her listeners, Koenig feels like she's been batted back and forth between the pillar and post of evidence and intuition. Adnan doesn't match anyone's notions of a killer, coldblooded or otherwise. He seems to have no history of anger problems or vindictiveness, and he just doesn't sound like murderer. But then, neither does Jay. And ultimately, the case comes down to Adnan vs. Jay. I happen to find Adnan more credible, but that's probably because I've "met" him through his recorded conversations with Koenig. And not only do I have a propensity to see wrongful convictions everywhere, but I know I'd have a hard time believing anyone I knew well could commit such a horrible crime. I could not do Koenig's job because by the second phone call I'd be hopelessly partial.

Even the most seemingly factitious evidence -- those cell records -- upon closer scrutiny dissolved into a rat's nest of contradictory possible explanations and motives because what, after all, is more personal than a adolescent's phone calls? Did Jay and Adnan go downtown? Why? Who called Nisha, and did he mean to do it? (I see no reason why Jay might not have decided to speed dial Nisha's number while he was driving around with Adnan's phone, even though he didn't know her. He was a teenage boy and she was a reputedly cute girl, after all.) Why would Jay call Jenn's landline if he was in her house -- that is, if he even was in her house at the time and if it was even Jay who called her? The cell records don't match anybody's story, which is not that surprising when you consider that the "anybody" in that sentence consists of stoned teenagers who would be asked to recount events weeks after they occurred.

Teenagers. Does it even make any sense to apply what-would-I-do litmus tests to teenagers in the first place? Neither Josh, Jay's former co-worker, nor Koenig could fathom why Jay would help Adnan dispose of Hae's body. The more we learn about Jay, the more harmless he sounds. "He seemed like he was in way over his head," says Josh. But if anyone's going to do something as dumb as become an accessory after the fact to a murder in response to vague threats about "West Side hitmen," it's a teenager, a resident of that roiling kingdom of hormones, rumors, peer pressure and cluelessness. The very fact that every person involved in the case was an adolescent ought to have been tip-off enough that we were never going to get any straight answers.

As Koenig notes, there is really only one solid fact left in this case: Jay knew where Hae's car was. Jay almost certainly knows who killed Hae. He says it was Adnan, and if he's lying about that, then it's got to be to protect himself, if not from incrimination, then from retribution from the actual killer. And with all due respect to the Innocence Project, it's hard to believe he'd do that to protect Ronald Lee Moore, a burgling, raping, murdering ex-con. "Big picture, Sarah!" Deirdre Enright of the Innocence Project exhorts the journalist, but what could be bigger picture than the question of why on earth you'd finger a friend for a crime you know he didn't commit?

And here we are, right back in the tall grass. "Bereft of more facts, better facts," Koenig says, "even the soberest likely scenarios holds no more water than the most harebrained. All speculation is equally speculative." Maybe the DNA evidence will offer better facts, but even DNA -- what we've come, thanks to TV crime shows, to view as the emperor of all forensic facts -- can be ambiguous and inconclusive. From the Asia McClain alibi to the Nisha call to the pay phone at Best Buy, "Serial" has been one tantalizing mirage of better facts after another. When we arrive at the scene, however, those facts turn out to be equivocal or simply irrelevant.

So, yeah, this did turn out to be a story about the elusive nature of truth, because you know what? The nature of truth is really fucking elusive: Deal with it. To judge from the number of people expressing their unshakeable convictions regarding Adnan's guilt or innocence, this is not just an annoying twist in a popular podcast but a reality we need to be reminded of every single day. I'd vote for having it tattooed on the back of some people's hands. In her beautifully written closing remarks, Koenig states that she would have voted to acquit Adnan if she had been a juror but as "just as a human being walking down the street," she wouldn't swear to his innocence, even if she mostly thinks he didn't do it: "As much as I want to be sure, I'm not."

It's a great conclusion, but the runner up for best moment in this particular episode was Koenig's interview with Hae's boyfriend at the time of her murder, Don. Since Don wouldn't speak to the mic, she has to summarize his remarks, but a clear picture of Hae comes through. Don describes how, as they worked together at LensCrafters, Hae would tease him about when he was going to take her out. He recalls how he loved her assertiveness about that, and says that his memories of her genuine friendship, as well as their shared love, have stuck with him over the past 16 years.

Some listeners think Hae has been obscured by the podcast's focus on the minutia of the case, but I disagree. Between the voice of her diary and the way her friends talk about her, she has become a more vivid character to me than anyone else in "Serial." Don's story made me see her, joking around during the slow times in a suburban eyeglass shop, making a play for an older guy and grounded enough both to recognize his need for a little self-image pep talk and to offer one. It seems inconceivable that anyone would want to destroy a person like that. Hae, Hae: even in second- and third-hand stories, she is so strong, and so brimming with life that sometimes I forget for a moment that she's dead. And yet that's the only thing we really know for sure.

Shares