I met my pederast in a Los Angeles alternative radio station. I thought maybe I could get a job cleaning studios, something menial, off the books. Something to shelter me, if only for hours, from a home life defined by violent alcoholism and devastating mental illness.

Like all predators, Scotty had refined his vision to sense weakness so as to flip it to his advantage. He was a lightly gym-toned guy in Lee jeans and film company Polo shirts whose film star cheekbones were the gift of a mother he despised and whose shock of glistening black hair a genetic hand-me-down from a cruel, long-gone father. (Scotty’s name and some identifying details have been changed.)

He’d listen intently when I talked about Roxy Music, Krautrock, Harry Partch and whatever else was obsessing me about music -- my only refuge -- at the time. I couldn’t afford to think it odd that a top-tier, 30-ish film/music tech like Scotty should strike up a conversation with a 15-year-old like me.

I was too starved for validation, too isolated in a lonely new struggle with the symptom onslaught of what would, 20 years later, be diagnosed as bipolar disorder with its abrupt panics, hammering melancholies, and dizzying sense of bodily dislocation. More than anything, I was an attractive target.

He gave me a tour of the station -- at the time, “alternative” was not the ossified corporate format we now associate with the word. It was more an adjective encompassing a plethora of non-Top 40, post-counterculture stations trying out all manner of oddball approaches to programming and content.

We explored the on-air studio, a new and towering antenna, the musty analog-cool repair rooms. His breezy affect was soothing and worldly at once. As if sharing a deliciously secret joke, Scotty told of how he’d bamboozled the station into paying him top dollar for freelance maintenance duties even as he prepped for a new high-tech R&D gig for a major studio.

By midnight of our first day, Scotty, understanding that the best way to my heart was through my ears, encouraged me to rifle through the station’s breathtaking record library.

Then we smoked hash and weed. Snorted lines. I got so wasted I said the Derek and the Dominos sleeve was melting. He laughed. A few days later he said I could work on a radio show.

I never did.

In the drama of the serial predator every boy becomes a conquest object whose value is based on a margin of difficulty. As a straight adolescent who lived with his lower-middle-class parents and dreamed of becoming a professional musician, I possessed a certain ratio of difficulty that appealed to Scotty. He was the sort of “chickenhawk” who not only demanded that his sexual conquests look as young as possible, but also present the thrill of the chase and eventual submission.

Another strain of predator prefers that their boys approach them in the adolescent miscalculation that their looks will buy them drugs, safety and opportunities, unaware all three will disappear when their stock value craters at a certain age, one that usually coincides with the appearance of any body hair.

So, another entry in the oldest Hollywood story, and it is not a gay story, it’s a power story. A monster story, pace Fatty Arbuckle, Roman Polanski and R. Kelly.

But what caught my eye about the Singer report was that damned luxe house, how that alleged boy-toy debauchery McMansion reminded me of a similarly opulent operation that Scotty dragged me to often, and it hit me:

You never hear from the boys themselves. You never hear our story.

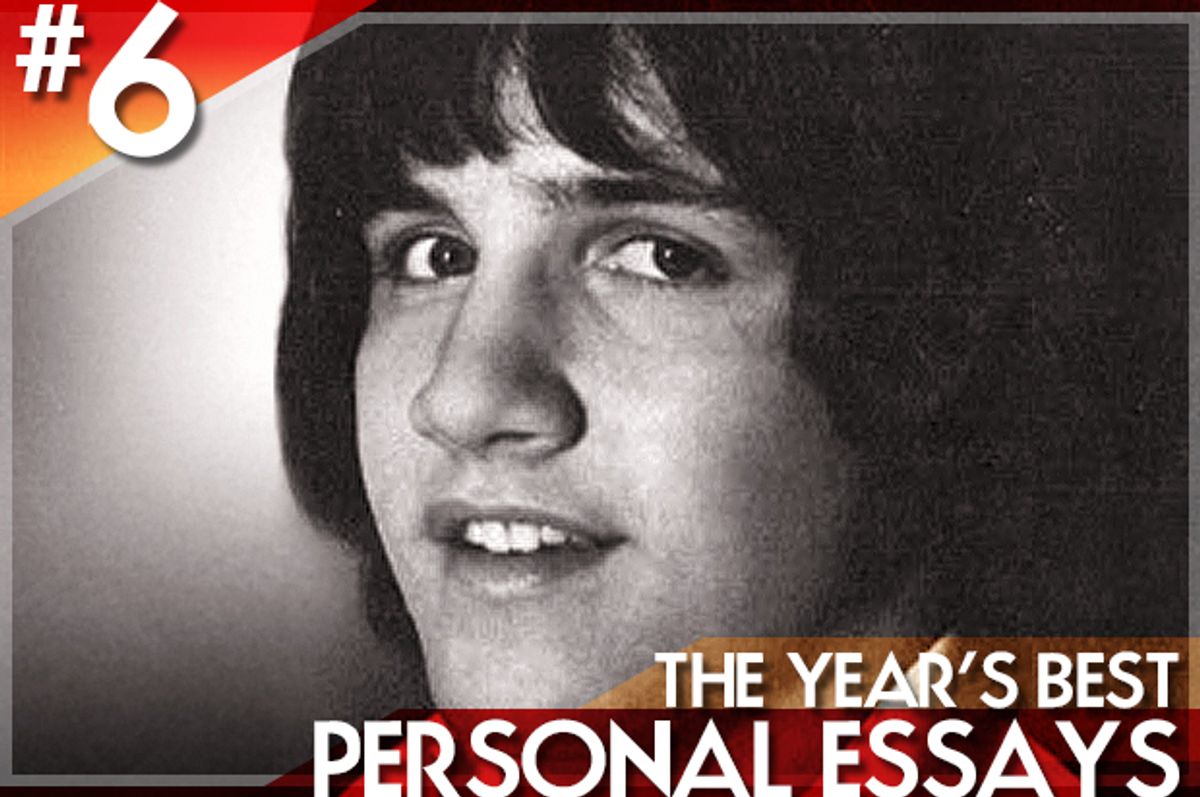

Soon after meeting Scotty, he was already devising his attack strategies and who could blame him? I was a NAMBLA dreamboat. Blue eyes, porcelain skin, hairless, pretty if you like to have sex with, well, children. Squint a little and I could pass for 14. Take a 'lude and I was 12.

Scotty decided that nothing less than a relentless psy-ops campaign would score him my cherry. Whatever problem I had, it would have to be established that he was the only viable source for a solution.

Endless supplies of kick-ass drugs were given/withheld so as to connect him with my idea of the pleasure principle, to reinforce his theory that doctors were useless middlemen, and to plant doubt wherever possible.

Did my school friends have Valium when I panicked? Did they understand my dark spells? Or that I was an old soul? No, they did not.

As much as the drugs alleviated my panic attacks, and as much as Scotty’s access to the drugs alleviated my anxiety about being anxious, he also used to instill more of it in me.

He warned of a terrible life of mediocrity if I didn’t at least try queer sex a few times: All great artists did.

Furthermore, as a person in the biz, he stressed that I needed to understand the music I was trying to make would fail utterly unless I started adding other elements: needless to say, elements that he liked. He was terribly sorry, but I needed to understand the way of the world.

A year or two passed. The blast radius of Scotty’s pathology came to include my father. When my old Toyota died, Scotty bought me a new sports car. My father, who just didn’t have the money, stared at the ground, emasculated, and accepted Scotty’s largess at the cost of his self-worth. (There’s another heartbreaking possibility -- that my father ultimately accepted, even welcomed, Scotty, whose largess removed so many of his own responsibilities.)

Scotty became emboldened with how he isolated me -- it’s what predators do. More nights were spent wasted at dingy chickenhawk bars, at the Odyssey, Geno’s, the Chick Shack. I’d try to melt into the black-brick walls, trashed and stupid on ‘ludes.

At the same time, Scotty was losing me. As messed up as I was, the musician in me, the young man in me, was maturing.

Clearly, extreme measures must be taken.

And so he told me about this amazing house. He made it sound like a West Coast Warhol Factory for men who like boys, patronized by the Industry’s most savvy below-the-line talent. He was working to get us in.

But first he took me to Yosemite Park and paid for a cabin in the woods with no electricity.

When I started to have a panic attack, he said I was “being a pussy” because I was afraid to cuddle with him like a normal person. Then he left me there, hundreds of miles from home, to prove how much I needed him.

It’s amazing what you can do to a child once you’ve tenderized him just right. You can, as Scotty did with me, incubate entirely new ways of being frightened, of feeling acidic mistrust and self-contempt. Like the Bacon-esque images of twinks being sodomized by cruel lions that Scotty liked to decorate his coffee and end tables with for god knows what sick reason, there are many things that are his that I will never be able to entirely clean out of my head.

One night he finally made his sexual move. Brushing his hand away, I said, "I’m sorry, but please, no." He stopped, but only, I believe, because my parents' room was right next-door.

By the time he actually took me to The House, I was primed. Disconnected. Able to become less-than-me depending on the situation.

In retrospect, the incredible thing is that, in his twisted way, Scotty thought he was doing what was best for me. That he was a helper. A good guy.

Anyway, The House. It was a sprawling mansion-ette off Mulholland Drive whose décor was upscale “Logan’s Run” as imagined by Halston, all tacky beige-on-silver built-ins with an immaculate black formica foyer, ‘70s futurism minus irony.

There was one huge, murky space with low lights, a haze of hash oil smoke and no couches, just a few low-slung tables with fist-size mountains of blow and huge silvery throw pillows. Hallways led from this space to bedrooms. Boys in highlighted feathered shags lay around, glaze-eyed, silent, like slinky veldt cats shot with tranq guns. The only sound came from a video game two boys played halfheartedly.

Every so often an adult would show up, size up the offerings, choose, and leave with a boy. The video gaming would then stop: Like any herd recently thinned, it took a few minutes for the children to readjust.

Scotty whispered I was better than this trash. And he needed my opinion. In one of the rooms. Which was empty save for an incredible stereo. He asked about the bass response on a remastered Elton John record. He wasn't a fan, he just needed my response to the EQ mastering curve. By now, actually screwing me was almost beside the point. His peers had seen him come in with me, and I'd gone directly to a room with him.

And anyway, as I neared 17, my sex-thing value was approaching negative zero. Plus, life was pulling me away from Scotty. After high school graduation, Vi, a badass dyke friend, asked me if I wanted to go to beauty school. I said sure, cool, whatever. Not long after that, the power pop band I was in got a record deal.

Then, finally, an epiphany: I was on Hollywood Boulevard and somebody’s Ford Comet radio played the Sex Pistols’ “Pretty Vacant” and so let loose cleansing fires of punk’s rage and my earned anger, which, combined with therapy, broke the first sick bonds with this bastard.

And then I almost murdered him.

But before I tell you that part of the story, some absolute facts. Young brains are a fragile work in progress. The pressures, stress and adrenalin spikes of a young brain trying to cope with the high-stakes chickenhawk game and the chemicals of wretchedness that fester submerged beneath it all represent an inner space of scarring psycho-biology no lab can quantify.

What we do know, with absolute certainty, is that meth, speed and blow scramble the function of crucial neurotransmitters in the brain, which in turn damage fragile neural connections in a young brain. For life.

The same drugs and stressors will flood the young brain with dopamine, a neurotransmitter associated with reward and pleasure. If continued, the user will lose the ability to experience pleasure or satisfaction of any sort from life. Permanently.

A few years after I reclaimed my life, Scotty called. Said he was nearby, that he’d told his new, for-real, actual boyfriend all about me. Could he drop by?

At Sunset and LaBrea he pulled the car over. "Ian! Did I tell you or did I? Isn't he gorgeous!"

He was a child. I'm guessing a younger shade of 11. No way a teen. The world turned blood red with rage as I imagined a parade of raped Scotty-victims past, present and future, children used up and cast away while their monsters got away with wrist-slaps because that’s how we do it in the U.S. of A.

Scotty saw what was in my eyes and actually flinched. Then he gathered the child in his monster arms, stared in my eyes, and gave him a sloppy French kiss.

Had I a gun, I’d have emptied the clip in that smile. But I didn't have a gun. And something shut down in me as I let him ride off with his new tiny victim. Who in due time -- his brain a neurological wreck, probably addicted to something, if only his continued ruination -- would be ditched when age made him of no further amusement to his users.

I want readers to understand that this is what we are talking about when the media yatters about another big-deal director, another priest or everyday schmuck with a child use problem. That these are the stakes.

Do I still think about Scotty, aside from this article? Yes. In nightmares.

Shares