The day before Johnathan died there was an ice storm in Texas. The air was so cold you could see your breath. Icicles hung from every tree branch and rooftop, and the roads were so slick that schools were closed. The ice storm would be the reason our marriage paperwork was never signed. Johnathan had proposed to me six months earlier, and only days after receiving his execution date, he had tattooed my name across his left knuckles.

As the roads began to clear that morning, I piled in the car with Johnathan’s father and his best friend Devon, and we made the 300-mile drive to see him one last time. We stayed in a hotel near the prison death chamber where they had transported him. We checked in, bought alcohol and tried to drink ourselves away from reality, which was that a man we loved would be put to death the following night.

It was only days before that Devon and I seemed like strangers to each other. Now, she and I were eternally bonded. Too anxious to go to bed, we stayed up talking and laughing and crying. Death, life, darkness, light. We stared at the clock. We dreaded the end. We wondered: Was he scared? Was he cold? Could he sleep?

I told her the story of meeting Johnathan. How I wrote to him as part of a court-ordered community service, a program that sent reading materials to prisoners. That letter kicked off an almost year-long correspondence that brought me to Texas on a Greyhound bus. His family -- even his fiercely protective sister Genia -- had welcomed me with open arms. His father made me hot chocolate every morning, his brother lightened the mood with his whimsical sense of humor, and both his sisters were always there for me. It all happened so fast I didn't think about what the end would mean, or how soon it would come. I was too immersed in the bond we shared.

Secrets were foreign in our world. Our connection was rare and intense. I told him everything: My adolescence in a series of foster group homes marked by neglect and abuse. How I became addicted to heroin at 16. Johnathan didn’t judge me; he encouraged me to stop wasting my life.

Johnathan had barely passed his teenage years when he committed his crime. The way he told it, he was helping his ex-girlfriend escape her father in the middle of the night. He took some of her father’s belongings, too, and was about to pull away when an off-duty police officer in the neighborhood abruptly stopped him, never identifying himself as a police officer. The man held a loaded gun to his head, and Johnathan shot him, multiple times. He told me it happened on instinct, that he was in fear for his own life and that everything happened within a matter of seconds. The name of the victim was San Antonio Police Department officer Fabian Dominguez. The court records reflect that Dominguez was in uniform at the time, but Johnathan told me he was wearing a black coat that covered most of it and in the pitch black night he could barely see him. Johnathan wrote a confession upon his arrest.

He was guilty, but I never believed Johnathan should die for his crime, and not just because I don’t believe in capital punishment. His sentence was so severe; one of his co-defendants, Paul Cameron, was convicted of life without parole for simply accompanying him that night. But Johnathan was living in a conservative state, had no access to good legal counsel and had unknowingly killed a police officer. He never had a chance.

On the morning of the execution, we hustled to the famous “Walls Unit” in Huntsville, which had executed more than 500 people to date. One by one we passed through the metal detectors, and I walked down the hall to a small cage covered with a metal mesh gate.

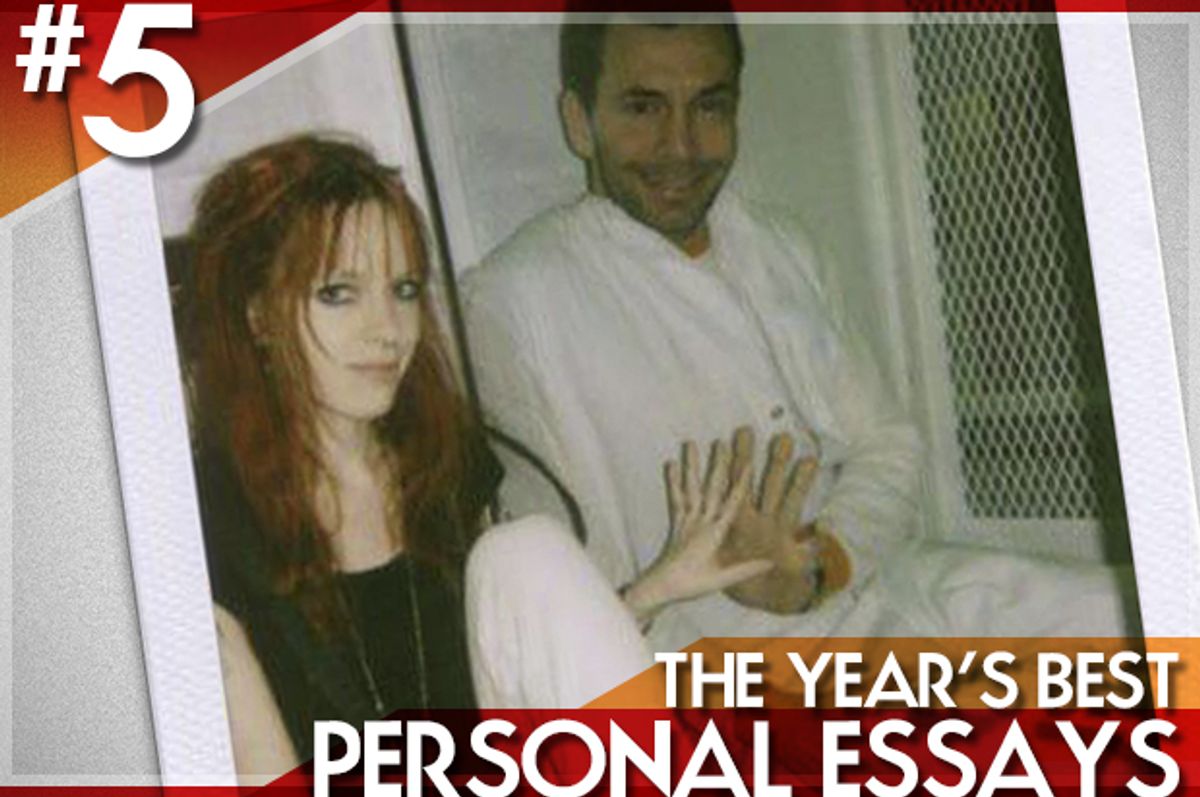

Johnathan's smile was beautiful as I sat down and searched his brown eyes."Look," he said. “No bulletproof glass this time.” I held my hand up to his. This was one of the few times our cells would rub off on each other and we were able to touch. His hands were big and warm and the connection felt good. I pressed my lips against the gate and we kissed and exchanged breath. For a moment I forgot about the gate, the guards, the glass. For a moment we were just two people, madly in love.

Then a guard dragged me back to my seat, and I was back again, looking at him through a cage. "Did you sleep last night?" I asked him.

"I had to,” he said. "They confiscated all of my property."

"Why?" I asked.

"Something about finding a razor blade,” he said.

I flashed back to a conversation we had when I was visiting him at his previous unit, back when we were using sign language to discuss escape plans. He used to say we would meet in Canada, because even if they found him, Canada refuses to extradite death row inmates. That dream kept me afloat day by day, even if it was a raft built on denial. He talked about the two of us, wandering through the woods together on our way to freedom.

"And what if it fails?" I asked him that day. He put down the phone for a second, took his shoe off, lifted up the sole and pulled out a shiny razor blade taped to the bottom. Then he put his finger to his lip, motioning for me to be quiet. I couldn't. The gravity of the situation exploded at that moment, and I broke down in tears.

"Baby,” he said calmly, “it would be better than going the other way.”

Suicide is what his friend had chosen, just a few months earlier. Michael DeWayne Johnson was on death watch and refused to let the state take his life. The night before his execution, he and Johnathan stayed up all night getting drunk on hooch. Johnathan wrote me a letter that night. It was cryptic, and I shook when I read it.

Dear Lily, It's 2:00. Me and Michael have been up partying all night. It's his last night.

It's 2:05, the party is winding down.

It's 2:10, Michael is telling me goodbye.

It's 2:19, I can hear him gagging and coughing.

It's 2:21, I see blood through the hole in the wall.

It's 2:25, I am putting my hand up against the wall that separates us.

It's 2:27, I told Michael that I love him.

It's 2:30, I can't hear any noise or movement anymore.

It's 2:31, a guard came by to do checks and then ran for help.

It's 2:35, The guards are putting Michael on a gurney and shaking their heads. There is blood all over the sheet that is covering his body.

It's 2:39, they are pushing Michaels body down the hall.

It's 2:45, I'm alone in my cell. My best friend is gone.

Michael Dewayne Johnson had broken a blade off a shaving razor and slit his own throat. Left on his cell wall was a message written in his own blood: "I didn't do it.” I tried to imagine the determination this would require, to dig that tiny razor deep enough across his neck, again and again, to puncture his throat till he gagged and suffocated on his own blood. It's a brutality that goes against our survival instincts. Now it was Johnathan’s turn to stare down his own end. Both plan A and B had failed. So I held onto his fingers through the metal mesh gate and kissed him again, hungry this time. The guards just shook their heads. "Give me some of your fur,” he said. He called my hair fur and my hands paws. His nickname for me was “chinchilla.” I ripped out a piece of my hair for him and passed it through a small hole in the gate. He put it in his mouth.

"Did you just swallow that?" I asked.

He nodded. "Now I have a piece of you inside me,” he said.

"I hate this,” I told him. “And why is Jennifer going to be there?” I was referring to the dead cop’s widow.

"She's got a right to be mad, baby,” he said. “Don't hate her. Hate the prosecutor. Hate the state. Hate the justice system, but not her.”

I knew he was right. Johnathan was deeply remorseful for his crime; it weighed on him heavily. But I felt like she was doing to me what she hated Johnathan for doing to her. She’d told the newspapers she wasn't interested in revenge, but now she was going to be there to watch my man die.

Johnathan looked down at his watch. Taped to it was a small picture of us. Time ruled him, down to the seconds.

"Hey, let's just live in this moment,” I told him. "I'm here with you now."

He nodded unconvincingly. "I had a dream about you,” he said with a smile.

"Oh, yeah?" I asked.

"You've become my fantasy girl big-time,” he said. “If I was out there with you, we'd have a bunch of little Lilys running around.”

I laughed at the mental image.

"Time's up,” the guards interrupted.

"Fuck you,” I shot back at them. I turned back to Johnathan. "You might get a stay,” I said. "They even talked about it on the news. They said because of the weather you might get a temporary stay of execution, and we filed your last appeals.”

He looked down again. "Don’t bet on it, baby."

"Ma’am, it's really time to go,” the guards said. I climbed up on to the chair to kiss him one last time but couldn't quite reach his lips. Then there were guards grabbing my arms, escorting me away as I cursed them. Tears welled up in his eyes, and he punched the cage.

I got back into the car and felt the whole world collapse around me.

Afterward, Johnathan’s family and close friends gathered in what’s known as the hospitality house, run by Christians, where the chaplain would brief us on what to expect as a witness to an execution. There was a memorial on the wall, which included pictures of every person who had been executed in Texas in the past two decades or so. The last picture was Carlos Granados, who had been put to death just a week earlier.

The chaplain sat us down. I curled up next to Devon, and she put her arm around me. We both cried as the chaplain described the procedure in gruesome detail.

A phone rang, and it was Johnathan.

"That was some good kissing, furry,” he said after I answered hello. A smile spread across my face hearing his voice. We bullshitted for a while. I forget everything we talked about. I asked him what he thought happened after death. "I'll find out,” he said.

The phone was passed around. I went into the bathroom to cry. The phone was eventually returned to me. "I have to get off the phone soon,” he said and then paused. “I want you to know that you came into my life at the perfect time, and I couldn't have asked for a better girl in my corner. Without you, I would have died lonely and incomplete.”

"Promise me that we will see each other again,” I said. “After tonight. Do you believe that we will meet again?"

"Yes,” he said.

"And you really believe that? You’re not just saying that?” I asked.

"I believe it,” he said. He told me to stay in San Antonio for a while so that his family, Devon and I could take care of each other in the aftermath. He told me to stay off the heroin. He told me he loved me one more time, and then there was silence at the end of the line. That was the last time Johnathan Bryant Moore heard my voice.

A knock on the door. "Lily, it's time,” the chaplain said. We shuffled into the van and rode back toward the death chamber prison. Johnathan’s brother held my hand. Devon looked back at me. "Let’s not say anything out there,” she said. "Let's not give these reporters anything more to talk about.”

“Think Jackie O,” John’s brother Walt said. And so I thought of Jackie O with her dark sunglasses and calm demeanor after Kennedy was assassinated. How she never showed her emotion, even when paparazzi stalked her.

I felt nauseated when we arrived. I walked past reporters, cameras and dozens of police officers who were there, thinking this was justice. The SAPD had chartered a bus to stand outside for Johnathan’s execution. On the other side of the road there was a small vigil of anti-death penalty activists.

There were two rooms for witnesses to the execution: One where the victim’s family could watch and one where we could be. A phone rang. A false hope came over me: Maybe it was the governor, calling to put a stop to this madness. Instead it was the warden, saying they were ready for us.

I never could have prepared myself for what I saw. My man’s arms were strapped down and stretched out, a tube already in his vein, a white sheet covering him up to his chest. It hurt me to see him so dehumanized, unable to move but still shaky. His last moments recorded and watched. He turned his head and looked into my eyes. I knew he couldn't hear me, but he read my lips as I said "I love you" one last time, and he said it back. I unzipped my hoodie to show him I was wearing his prison shirt in solidarity. He nodded at me. They asked if he had any last words.

"Yeah,” he said, speaking into the microphone positioned above his mouth. He looked to the other side of the glass. "Jennifer, where you at?" he searched for the eyes of the woman he had left widowed 12 years ago. His lip quivered. "I want you to know that I’m deeply sorry for your loss. It was done out of fear, stupidity and immaturity, and I didn't know the man but for seconds before I killed him and I didn't realize what I had done until years later in prison. I am sorry for all your family and my disrespect. He deserved better.”

Then he looked at me. “Lily, you stay off the heroin,” he said. "That’s what you do.” He told his family he loved them. “Quit the self-destruction, Lily,” he said again. A single tear slipped from underneath his glasses and then he said, “OK, warden, I'm ready."

I felt faint. Devon held me tightly as I worried that maybe I couldn't stand. She was whispering the Hail Mary incessantly. First was the anesthesia. He started to say something again and then his mouth froze as the drugs took over his body. The second drug collapsed his lungs, and we all heard a harsh exhale. The third stopped his heart.

It lasted 10 minutes, but it took an eternity for him to die. I pressed my hand against the glass and cried “no" over and over again. His eyes were still open. Blood filled the tube, and we gasped as all color faded from his flesh. I felt an amazing energy come over me in a wave as he died. I felt him die.

He was confirmed dead at 6:21 p.m. A sheet was pulled over his head, and they opened the doors. The four of us held hands and walked outside into the cold night past the cameras. I saw dozens of uniformed officers waving blue glow sticks.

Devon and I sat in the car in silence, looking out the window at the icy starless sky. I was 20 years old, and I had just watched the man I loved deeply killed in front of me.

"I think he's OK,” Devon said finally. "I think he's with Bobbi.”

Bobbi was his mother, a wild-hearted tattooed woodswoman and survivalist who rode motorcycles, kept a garden, had native blood, believed in spirits and opened her home and heart to stray animals and children. Devon told me a story about one time that Johnathan’s friends showed up unannounced and were met by his mother at the door with a shotgun, barefoot in her nightgown. "What the fuck do you want?" she asked. His friend used to say they wanted a woman like that.

I am told that depression killed her. She was never the same after they locked up her son. At the trial, she told the prosecutors and jury that they were full of shit. I wish I had gotten a chance to meet her, but she's come to me in dreams and her memory helped carry me when I couldn't walk that night. If there is another side, I hope they are there together.

Most nights I can't sleep. I lay awake sweaty with the same sad dream: Johnathan strapped down in the execution room behind the glass. I want to touch him, but I can’t.

Other times I am overcome with the strength to go on, to "stop living accidentally and start living on purpose," as Johnathan would say. And I will. For the boy with one gun in his hand and one aimed at his head. For the girl with needle tracks on her arm and scar tissue on her heart. For both of us, who found hope when it seemed impossible, and love after a lifetime of mistakes.

Shares